This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Development as Freedom" by Amartya Sen. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Is poverty a social problem? Why is poverty heavily associated with wealth and income? Should it be?

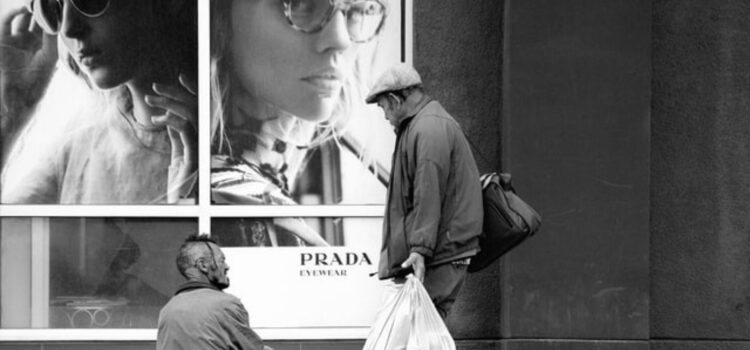

While income is still widely considered an income problem, economist and philosopher Amartya Sen says that poverty is created and enhanced by a lack of human rights and freedom. In Development as Freedom, Sen claims that focusing only on income just creates more social issues.

Let’s look at three reasons why poverty is a social problem.

Why Poverty Is a Social Problem—Not an Income Problem

Sen contends that focusing on income to assess development doesn’t fully reflect people’s welfare or well-being. Consideration of freedom and accepting that poverty is a social problem provides a more well-rounded picture. Sen views income-centered development as inadequate because it overlooks aspects of welfare that people value. Here are three oversights of the income approach:

- Varying effects of GDP on health

- Social costs that persist even with income transfers to the poor

- The possibility that overall welfare may improve without strong GDP growth

We will consider each of these in turn, providing examples Sen uses to support each claim.

1. Increased Wealth Doesn’t Improve Health

Often, income alone doesn’t tell the full story of well-being. For example, Sen notes that African Americans have per capita incomes much higher than the average person living in developing countries like Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, or Jamaica. However, African Americans have lower life expectancies (a measure of well-being) than people in each of these three nations.

Therefore, the mere fact that they’re wealthier doesn’t necessarily translate to better standards of living. By focusing more on the five essential freedoms, (democratic rights, commercial liberties, public provisions, ethical guardrails, and safety nets), we can better understand the causes of the disparities between income and welfare.

Specifically, Sen argues that improving income alone doesn’t raise life expectancy. For example, Sri Lanka and Namibia each have a GDP per capita of around $4,000. However, Sri Lankans have a life expectancy of 77 years compared to 63 years in Namibia, likely because of their health care system.

Another key contributor to life expectancy is a public expenditure, specifically on health. Sen explains that increases in per capita GDP are correlated with increased life expectancy—but only when that new wealth is used to eradicate poverty and improve health care.

2. Income Transfers Don’t Address Social Problems

Eradicating poverty by increasing people’s income through government programs doesn’t necessarily improve their well-being because it often doesn’t address social problems. For example, Sen explains that many European nations, which typically have unemployment rates above 10%, generously supplement the incomes of unemployed people. But research indicates there are numerous social costs associated with being unemployed, including negative effects on physical and psychological health, as well as social ostracism.

Sen argues that European unemployment subsidies don’t increase overall well-being because they fail to account for these residual costs. Helping the disadvantaged requires more than just subsidizing their incomes, it requires expanding their opportunities.

(Shortform note: Research suggests that unemployment has a substantial negative effect on individual health. Sen argues many of these negative effects aren’t considered in economic metrics like GDP, nor can they be fixed through income transfers alone. Unemployed people often suffer a host of psychological impacts, like an increased risk of depression and lower levels of marital satisfaction.)

3. Social Services Don’t Have to Rely on Economic Growth

Should countries focus first on increasing GDP as a means to eradicate poverty and prioritize health care? Or should they focus first on devoting their modest resources to these public provisions?

Sen says poor nations shouldn’t wait for economic growth to provide social services. The reason has to do with the relative costs of poor nations making such investments. Because social services like education and health care are labor-intensive (they rely much more on people rather than technology), the costs of providing them sooner are lower, too.

If a nation waited to get wealthier before making these investments, that wealth would increase the costs of these investments. According to Sen, this happens because jobs in social services demand higher wages when overall incomes rise. By waiting for a rise in wealth, nations are just contributing to the social problem that is poverty.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Amartya Sen's "Development as Freedom" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Development as Freedom summary :

- The five types of freedom that are integral to economic development

- How democracy can prevent famine

- How empowering women helps communities