This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Caste" by Isabel Wilkerson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Why has there been an increase in the number of suicides and drug-related deaths amongst middle-aged, white Americans? Could the castes in America be part of the reason?

When the caste system that mistreats people of color in America was established hundreds of years ago, we couldn’t have predicted the repercussions it would have on the future of white Americans. In her book Caste, Isabel Wilkerson explores how the modern focus on diversity and equality is pushing white Southerners to the edge.

Continue reading to learn about the unintended consequences of the castes in America.

The Impact of the Caste System on White Americans

Although the dominant caste’s actions aim to oppress the subordinate caste, Wilkerson believes the effects often create repercussions for dominant members, as well. As an example, she cites a 2015 study in which researchers discovered an increasing mortality rate in middle-aged white Americans from middle- to lower-income demographics between 1998 and 2013. During this period, Americans of similar age and class from marginalized groups didn’t experience this same increase, nor did those from other Western nations. In fact, both groups had experienced decreases in their mortality rates.

According to the author, many of the deaths experienced by white Americans aged 45 to 54 were “deaths of despair,” such as suicide, drug overdoses, and substance-related diseases. Some hypothesized that these deaths were due in part to stagnating wages in blue-collar jobs that created financial instability. Yet other Western nations and marginalized American groups also experienced this financial instability and were not dying at faster rates. Therefore, Wilkerson argues, researchers turned to another hypothesis—“dominant group status threat,” or the insecurities that arise when people in the upper castes in America feel their dominant status slipping as other groups climb the ladder.

(Shortform note: The authors of the 2015 study note that the number of additional lives lost to deaths of despair during this period (compared to the 1979-1998 rate) is comparable to the number of lives lost to the AIDS epidemic in the United States. This shows the huge impact of the phenomenon, perhaps even bigger than Wilkerson imagined.)

| Dominant Group Status Threat Predicts Support for Trump Dominant group status threat is a powerful force. While Wilkerson links it to negative health outcomes for white Americans, it can also predict the outcome of presidential elections. A 2016 study showed that the rate of “deaths of despair” in a given county predicted support for Donald Trump in that county in the 2016 presidential election. Additionally, in Strangers in Their Own Land, Arlie Hochschild argues that white working-class voters are facing a loss of social status, and voted for Trump because he symbolized the return of that status. |

The Loss of Social Equity

Why did dominant group status threat develop among white Americans in the 21st century? Wilkerson argues that the changing landscape of justice after the Civil Rights Movement likely created aftershocks in lower- and middle-class white Americans’ sense of security in their status. They were suddenly faced with a different reality than that of their parents and grandparents, who’d enjoyed privileges because of their white skin in both the social and economic spheres. Many felt that their main source of identity—their superior status as white—was slipping through their fingers. Without it, they’d be forced to accept the realities of their difficult economic situation without the comfort of upper-caste superiority.

(Shortform note: Additionally, in Strangers in Their Own Land, Arlie Hochschild describes how this sudden loss of status and identity happened at the same moment that people from marginalized groups (such as women, people of color, and LGBTQ people) were beginning to celebrate and find value in their identities. This was an unacceptable role reversal for many white Southerners.)

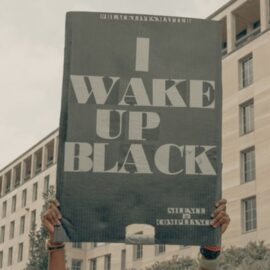

Rather than face this existential crisis head-on, Wilkerson argues, many white Americans turned their discomfort with subordinate advances into rage. They angrily believed that the rising status of Black people meant a lower status for white people—and a threat to their very existence. (Shortform note: This zero-sum mentality can be dangerous. For example, the white man who murdered nine people at a historically Black church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015 was motivated by the fact that “Blacks were taking over the world” and felt he needed to defend the white race.)

The Influence of Bias

According to Wilkerson, this discomfort exposed the dominant caste’s inherent biases against the subordinate caste. Inherent bias differs from overt racism in that the associated behaviors are invisible and often unintentional. Wilkerson argues that dominant caste members may act in prejudicial ways toward others based on preconceived judgments, even when they believe they’re progressive thinkers. The consequences of bias are disparities in who people hire, rent apartments to, sell houses to, admit into educational institutions, and provide medical care for.

(Shortform note: Jennifer Eberhardt goes into much more detail about racial bias and its causes in Biased. She argues that these implicit biases are the product of our natural impulse to divide the world into categories (like Black, white, male, female, and so on). Our brains use these categories as mental shortcuts to make sense of the world—instead of putting in the effort to get to know each individual person, we naturally make assumptions about them based on their category as a way to conserve mental resources. Those assumptions can result in prejudicial treatment.)

When Bias Backfires

Implicit bias in healthcare has detrimental effects for the middle and subordinate castes. Wilkerson argues that Black patients receive poorer care and less treatment than white patients do, despite suffering more illnesses. (Shortform note: According to a 2020 study, this pattern of medical prejudice is part of the reason Black people were 3.57 times more likely to die of Covid-19 than white people.)

Doctors are also more reluctant to prescribe pain medications to people of color than white patients. Wilkerson argues that biased beliefs about pain tolerance are at the root of this disparity. (Shortform note: Research supports Wilkerson’s conclusion. A 2016 study found that half of all white medical students surveyed held at least one racially-biased false belief about pain tolerance, such as “Black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s.” The same study found that people who hold these beliefs tend to prescribe less powerful pain medications to Black patients than to white patients in the same amount of pain.)

However, Wilkerson believes that, in withholding pain medications from marginalized patients, doctors actually safeguarded them from the catastrophic epidemic of opioid addiction. Conversely, in readily prescribing opioids to white patients, doctors created a pathway for this group to become consumed by this addiction—which is one of the most significant contributors to the increase in mortality rates of middle-aged white Americans.

The opioid crisis is not the first substance abuse crisis to hit American soil. However, according to the author, previous epidemics (like crack cocaine) mostly affected Black communities, and anti-Black bias prevented public health officials from investing resources into what they saw as a “Black problem.” Instead of providing substance abuse treatment solutions for these communities, they incarcerated addicts, resulting in the disproportionate number of black inmates in today’s penitentiaries. However, if officials had created treatment frameworks to help the subordinate caste address the crack cocaine epidemic, those systems would be in place now to help the thousands of white Americans suffering from opioid addiction.

| Lawmakers Treat Black and White Drug Users Differently Other scholars have discussed the U.S. government’s differing responses to the crack and opioid epidemics in more detail. For instance, in The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander describes how the U.S. government’s response to the crack epidemic was part of the highly racialized “War on Drugs.” In 1986, in response to increased concern about the dangers of crack cocaine, the government passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act—a law that established mandatory minimum prison sentences for drug crimes. However, the same minimum sentence applied to vastly different amounts of different drugs: five grams of crack cocaine (which was more common in Black communities) versus 500 grams of powder cocaine (which was more common among white drug users). In other words, the average white person caught with cocaine would have to possess 100 times more of the drug than the average Black person to get the same prison sentence. (In 2010, the Fair Sentencing Act reduced this disparity from 100 to 1 down to 18 to 1.) To contrast, the American opioid crisis began in the 1990s. However, unlike the crack epidemic, the government didn’t respond with an instant crackdown, and opioid abuse wasn’t declared a public health emergency until 2017. Researchers have noted the difference in language surrounding the two crises: Politicians and the media characterized the crack epidemic as a “criminal justice issue”, but they deemed the opioid crisis a “public health issue.” Even the legislative response was different: In 2019, a group of Democratic senators introduced the Opioid Crisis Accountability Act, which proposed to hold drug suppliers (in this case, pharmaceutical companies) responsible for the crisis, rather than individual drug users (nearly 90% of whom are white). This further demonstrates how American society views white people as helpless victims and Black people as violent perpetrators when it comes to drug abuse. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Caste summary :

- How a racial caste system exists in America today

- How caste systems around the world are detrimental to everyone

- How the infrastructure of the racial hierarchy can be traced back hundreds of years