This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" by Malcolm X and Alex Haley. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How did Malcolm X become a civil rights activist? Who was Johnson Hinton, and what did he have to do with it?

In 1957, New York City police officers severely beat up a Black Muslim man named Johnson Hinton. That incident eventually pushed the Nation of Islam—and Malcolm X—into the spotlight of America’s civil rights movement.

Read more to learn about the launch of Malcolm X’s activism.

Malcolm X’s Activism

Malcolm X’s activism in the civil rights movement started when he led a resistance movement against police brutality. In 1957, a Black Muslim man named Johnson Hinton had been attacked by New York City police and taken into custody. Accompanied by many members of the Fruit of Islam, Malcolm X demanded that Hinton be released for medical care. Hinton was finally taken to the hospital by ambulance. The Black Muslims followed and were joined by other Black people who were incensed by police brutality and excited by the possibility of organizing against it. Hinton had to have a steel plate put in his skull. He sued the city, winning over $70,000. The debacle got a lot of publicity, making the Nation of Islam a household topic.

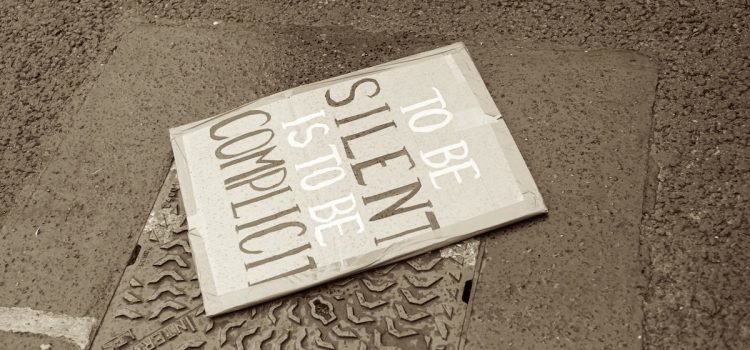

(Shortform note: The sum awarded to Hinton in 1961 was the greatest sum paid for police brutality in New York City history, worth over $760,000 dollars in 2023. Hinton’s case wasn’t the only case of police brutality that Malcolm X or the Nation of Islam fought against: According to experts, the Nation of Islam influenced the battle against anti-Black police brutality by responding with nonviolent acts of protest. However, Malcolm X eventually concluded that the Nation of Islam wasn’t doing enough and launched his own campaign against police violence. Because Black people are still more likely to be killed by police, the struggle against anti-Black police brutality continues today, such as with the Black Lives Matter movement.)

In 1959, a documentary about the Nation of Islam called The Hate That Hate Produced aired, broadcasting the organization’s radical views to the national stage for the first time—this catapulted Malcolm X to widespread recognition. He began visiting colleges as a much sought-after guest speaker; he also engaged in TV and radio debates to explain why Black separatism was necessary and to fight against accusations that he was inciting violence—in his view, he simply advocated resisting oppression. Because of the increased media attention, the Nation of Islam got more popular—and began to be surveilled by the government.

(Shortform note: The Hate That Hate Produced cast the Nation of Islam as reverse racists—a common criticism of pro-Black organizations that says that white people are targets of racism. Recent studies suggest that overall, white people think reverse racism is a bigger problem than anti-Black racism—an idea that became central to the battle against affirmative action, a policy that allowed colleges to take race into account in the admissions process until it was struck down in 2023. Because they posed a threat to the traditional anti-Black order of things, many Black leaders and organizations were surveilled by the government during the civil rights movement.)

Malcolm X used his leadership skills to recruit more converts with the aim of uplifting Black people and uniting them against racism. He explains that, initially, many converts to the religion were people who struggled with addiction. The Nation of Islam forbade all drug use, so, when someone wanted to convert, they had to give up drugs—a difficult but health-promoting process. Once they had, they’d seek out drug addicts they’d known in their former lives and help them through the process of getting sober. As the organization grew, it began to recruit traditionally successful Black people, including Christians. The Nation of Islam was successful because it gave Black people a supportive community and proactively helped them through their struggles.

(Shortform note: The New York Times reported that the Nation of Islam’s program for rehabilitating addiction was so successful that health professionals and probation officers turned to Malcolm X for advice about breaking addictions. One part of the rehabilitation process was to instill in each addicted person a strong sense of Black pride—they believed that Black people struggled with addiction because they couldn’t otherwise cope with living in a world that valorized whiteness and denigrated blackness and that a greater sense of Black pride would help them cope in healthier ways.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Malcolm X and Alex Haley's "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Autobiography of Malcolm X summary:

- Malcolm X explains why he believed what he believed

- The historical and sociological context surrounding Malcolm X’s life

- Why Malcolm X was such a controversial figure