This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Ways of Seeing" by John Berger. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the male gaze? How are women objectified in art?

The male gaze is the practice of portraying women in the visual arts from a perspective of a male viewer. According to art critic John Berger, through the assumed male gaze, the depicted women are perceived as objects of sexual desire owned by the spectator.

Continue reading to better understand the male gaze in art.

The Male Gaze in Art

Nude women were a prominent subject in European oil painting. Berger points out that, in the same way oil paintings depicted wealth using images of land and objects, women were also seen as property to be flaunted.

This raises the issue of the male gaze in art. Nudes, Berger says, are characterized by the objectification of the female “subject,” who through the assumed gaze of the male viewer is made into an object. Men who were wealthy or powerful enough to buy and commission oil paintings wanted nudes for the same reason they wanted oil paintings of valuable objects: to remind others and themselves that they were rich, powerful, and desirable.

Nude women in European oil paintings appear for the benefit and use of the assumed male viewer, who Berger calls the “spectator-owner.” He calls them this because the man who owns the painting “owns” the nude woman, and (in his mind) he’s also the reason why the nude woman is there—to display herself for him, the spectator.

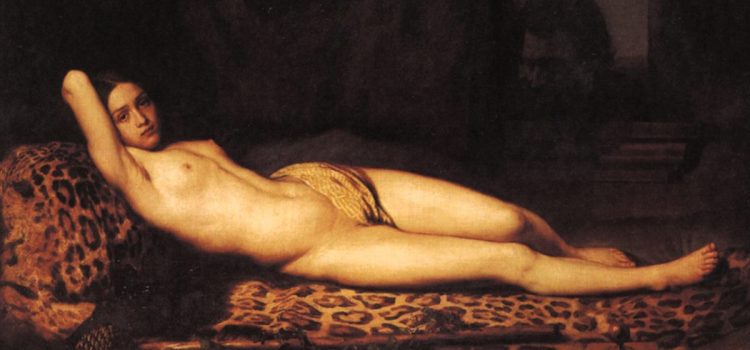

RECLINING BACCHANTE BY TRUTAT 1824-1848

Berger notes that the nude woman is often being viewed by two or more men: A male within the painting, and the spectator-owner. Despite being desired by one or more men within the painting, the woman shows her loyalty to the spectator-owner through eye contact or by positioning her body to face him. Berger says that the owners of these paintings enjoyed and requested this because it made them feel dominant in an imaginary competition.

Look at how, in the following examples, the nude woman is receiving attention within the painting, but her gaze and body language focus outward toward the spectator-owner:

ALLEGORY OF FORTUNE BY DOSSO DOSSI 1538

NELL GWYNNE BY LELY 1618-1680

SUSANNAH AND THE ELDERS BY TINTORETTO 1555-1556

| Contemporary Nudes According to Berger, the nudes of the oil painting tradition were highly focused on the spectator-owner and featured the male gaze within the paintings as well. Today’s nudes are less focused on being desirable, and more focused on breaking taboos. In many examples, the woman touches her own body and exudes a sexuality that up until recently was viewed as a character flaw. Since the “Me Too” movement of 2017, women have moved toward unapologetically embracing their sexuality and rebelling against the historical objectivity of their bodies. |

Naked Versus Nude

Not all naked paintings are nudes. According to Berger, to be naked is to be yourself, and to be seen by others for who you are—it is vulnerability and honesty. To be nude, on the other hand, is to hide oneself and be seen by others as an object—usually for sexual fantasy.

Mystification of the Nude

Now that Berger’s definition of a nude is firmly established, we can explore how this trend was and is mystified.

As Berger explains, the vast majority of paintings that depicted nudity were commissioned by wealthy men who wanted the illusion of owning the woman. The image was catered to his tastes in order to please him. This obscures the reality of what women actually looked like, how they behaved, and what their attitudes were toward their surroundings. What we are left with is not a record of how women were, but as of how the spectator-owners saw them, and how the painters depicted them.

By depicting women as a prize to be won, paintings from this time period oppressed women by creating competition among them and manipulating their perspective of their own gender. Berger explains that as long as women believe they belong to men, and that they must fit a conventional and submissive standard to be desirable, the men can maintain social, economic, and political control.

| Filters: The Modern Mystification of Women Berger notes that we don’t have an accurate idea of what women looked like during this time period because their image was manipulated and painted for the enjoyment of the male viewer. A similar phenomenon is taking place in social media in the 2020s—the use of filters. Hundreds of filters exist that can be placed over photos and videos (even live) with one tap of the finger on a smartphone. Though all genders use filters, the primary users are female. A filter is essentially a set of image manipulations that can be applied simultaneously and instantly. One moment you look like yourself, and in the next, you look like someone completely different. Their existence has changed beauty standards across the world and mystifies what women really look like. Just as we don’t have a clear understanding of what women looked like during the Renaissance, if someone 100 years from now looks back on photos from social media today, they too wouldn’t know how women of the 2020s truly looked. Rather, they will see the idealized image of the time, which is constantly in flux. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of John Berger's "Ways of Seeing" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Ways of Seeing summary :

- Why we don't need experts to "translate" works of art for us

- How the dominant class uses art and art criticism to “mystify” the working class

- How our experiences and beliefs influence what we see