This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Shock Doctrine" by Naomi Klein. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How did the UK adopt a neoliberal economy? Why did it take longer for Britain to implement neoliberal policies?

Although neoliberalism spread quickly and brutally through South America, it had a harder time gaining traction in Britain. There was an insurmountable conflict between free-market capitalism and democracy. Because neoliberal policies would hurt the majority of the people, they’d never vote for politicians who tried to implement them. Things changed when a seemingly insignificant military conflict altered the course of economics.

In this article, you’ll learn about the arrival of neoliberalism in the UK.

Struggles for the Chicago School

In 1981, the economist Friedrich Hayek—who taught at the Chicago School of Economics, where he was held up on something of a pedestal—took a trip to Chile to see what the Chicago-trained economists had created. He was so impressed with the free flow of money there that he wrote to his friend Margaret Thatcher, then-prime minister of Britain, and urged her to transform Britain’s economy in a similar way.

Thatcher, however, insisted that such an economic shock program wouldn’t be possible in Britain. Trying to implement neoliberalism in the UK would practically guarantee that Thatcher (who was already losing popularity) would be soundly defeated in the next election.

Thatcher Brings the Free Market to Britain

The 1982 Falklands War—or the Malvinas War if you’re in Argentina—was an 11-week struggle between Britain and Argentina for control of the Falkland Islands. While the conflict was trivial from a military standpoint, from a political standpoint it was exactly what Thatcher needed to boost her popularity.

Now that Britain had an outside enemy, the people were swept away by a wave of nationalism and militarism. They eagerly fell in line with the prime minister, who praised their patriotism and fighting spirit. The prime minister’s approval rating more than doubled during this time, rocketing from 25% to nearly 60% as the otherwise meaningless conflict went on.

Thatcher used her new popularity to start imposing the policies that she’d told Hayek were impossible. For example, when there was a coal miner strike in 1984, Thatcher framed it as another front of the Falklands War. She said that they’d fought the enemy without, and now they needed to fight the enemy within with the same ferocity and resolve.

Now that the workers had been billed as the enemy, Thatcher was able to bring the full power of the state against them. She used all of the surveillance and counterintelligence tools at her disposal, along with thousands of police officers, to break the miners’ union and end the strike.

By 1985 the union, one of the most powerful in the country, had capitulated. Nearly 1000 miners were fired, and other unions knew that going on strike or fighting for better conditions would risk bringing the state’s wrath down upon them as well.

With two victories under her belt, Thatcher started taking major steps toward a free market economy. Over the next few years, the British government privatized British Telecom, British Airways and British Airport Authority, British Steel, British Gas, and other formerly government-run industries.

A Different Type of Crisis

Margaret Thatcher’s efforts in Britain had proven that free-market capitalism didn’t necessarily need a dictatorship to whisk people away to torture camps. Rather, a national crisis could make the people fall in line. Now, all that Friedman and his followers had to do was leverage internal crises as effectively as Thatcher had leveraged the external crisis of the Falklands War.

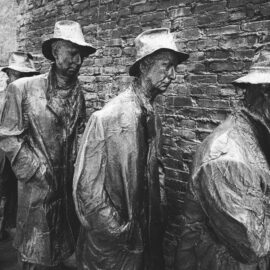

After the internal crisis of the Great Depression, the American left had made major gains by advancing the New Deal and the Keynesian policies it supported. Friedman was now determined that it would be his students, rather than Keynes’s, who would be ready to take advantage of the next crisis.

To that end, Friedman—backed by underwriters from some of the world’s largest corporations—built a collection of right-wing research institutes and produced a 10 part PBS miniseries about the importance of economic freedom, called Free to Choose. In short, he was laying the groundwork to make sure that he’d have broad public support when the next crisis hit.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Naomi Klein's "The Shock Doctrine" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Shock Doctrine summary :

- A study of the history of economic shock therapy

- How economic shock therapy gave rise to the disaster capitalism complex

- How communities are beginning to recover from the destructive shock treatments