Are you worried that you’ll lose your job to a machine? What’s the historical precedence for this concern?

Economist Robert J. Shiller points to several narratives that tap into fundamental themes that have shaped our collective understanding of past economic events. In turn, the narratives themselves come to have a profound influence on future events. One of these narratives entails machines taking over jobs.

Keep reading to learn about this recurring economic narrative that provides some needed perspective.

Machines Taking Over Jobs

Shiller writes that fears of technological unemployment have persisted throughout history, including the Industrial Age and the present era of AI and automation. Indeed, he writes that the fear of machines taking over jobs is a narrative with deep historical roots, dating back to the ancient Greeks. Throughout history, every significant technological advance has rekindled this narrative, often accompanied by riots and fierce protests as people grapple with the implications of automation.

This narrative gained momentum, Shiller notes, with the onset of the Industrial Age and continued well into the early 20th century. It reached its peak during the 1930s when many people attributed the Great Depression to technological unemployment. During this period, the fear that machines could displace human jobs was palpable, and it fueled concerns about economic stability and inequality.

(Shortform note: Some commentators agree that fears about the technological displacement of human workers are a recurring historical theme—and that these arguments have been wrong every time they’ve been advanced. Their proponents are typically called “Luddites”—named after a legendary figure in the early 19th-century British labor movement, Ned Ludd, who supposedly led English textile workers to protest against the introduction of labor-saving machinery during the Industrial Revolution. However, critics of the original Luddite movement argue that their resistance to progress was misguided, as the Industrial Revolution ultimately led to increased productivity, improved living standards, and the creation of new job opportunities.)

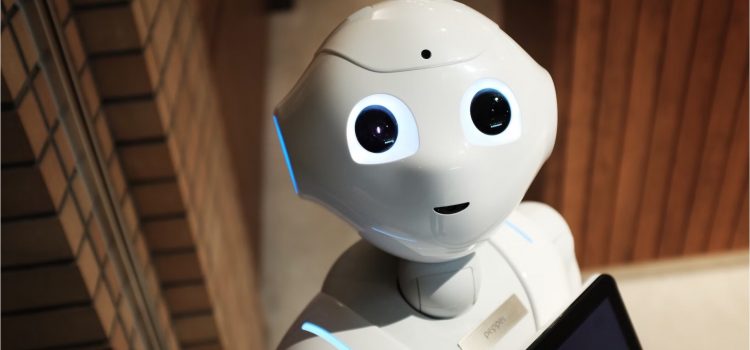

The Emerging AI Narrative

In the modern era, writes Shiller, computers and AI represent the latest manifestation of this narrative. Just as engines and machines once replaced physical labor, AI and computers are now poised to replace intellectual labor. The concern is that, if workers accept this narrative too deeply and come to fear their jobs will be automated in the near future, they may curtail their spending now, anticipating economic uncertainty. This reduction in consumer spending could lead to a decrease in overall demand, potentially triggering a recession. And, in a neat illustration of the self-reinforcing power of economic narratives, a recession might incentivize employers to invest more in money-saving automation as they seek to cut costs, perpetuating the cycle.

| Will Technology Create a “Useless Class”? Echoing the questions Shiller raises about automation, Yuval Noah Harari writes in 21 Lessons for the 21st Century that one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century will be a net loss in employment that creates a “useless class” of unskilled workers. While Harari argues that some workers will be able to get training in a new set of skills, technology will continue to change so rapidly that those new skills could also become obsolete a decade later. Even in fields that introduce human-computer teams, computers may eventually perform so well that they no longer need their human partners. Harari draws a contrast with the earlier waves of automation cited by Shiller. Throughout history, observes Harari, each new machine and labor-saving technology created at least as many jobs as it eliminated—for example, a piece of equipment that replaced a human laborer also required someone to operate the equipment and another person to do maintenance on it. Past innovations substituted human workers’ physical capabilities, but not their cognitive abilities. However, writes Harari, the dual rise of infotech and biotech is creating technologies that truly could replace the need for human workers. New discoveries in neuroscience have revealed that human skills such as analyzing, decision-making, communicating, and interpreting other people’s emotions are the results of specific brain algorithms. Now that scientists are coming to understand how the human brain uses these algorithms, technologists can increasingly replicate those processes with AI. As a result, not only can machines do a human’s job—they may even be able to do it better than humans can. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Robert J. Shiller's "Narrative Economics" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Narrative Economics summary:

- How human beliefs and actions, not statistics, drive economic outcomes

- The factors that contribute to the spread of economic narratives

- The significant economic consequences of the American Dream