This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The First 90 Days" by Michael Watkins. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Have you just been appointed a new role? Do you want to do something impressive to prove yourself to the higher-ups?

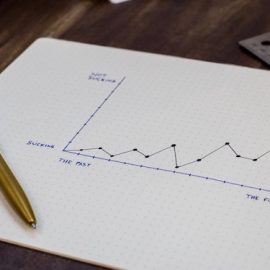

According to Michael Watkins, the author of The First 90 Days, the best way to get noticed and, more importantly, recognized is to secure some “early wins.” This will prop up your credibility and provide an opportunity to invest in key relationships that will be essential for a successful transition.

In this article, we’ll discuss how to identify areas for early wins and how to implement them effectively.

Identifying Areas for Early Wins

How can you identify potential areas for early wins? Many people are tempted to jump on low-hanging fruit that will result in quick wins but that will not contribute to longer-term goals and will not help build momentum for the harder work that needs to be done. To avoid that temptation, be sure to:

1. Choose areas for early wins based on the expectations for your position and as laid out in prior conversations with your boss and stakeholders. Those expectations provide insight into the company’s business goals, which should be at the heart of your early wins.

2. Ask whether the possible early wins that you have identified will help introduce new patterns of behavior that will support a broader vision for change. For example, perhaps you have noticed a lack of focus (marked by no clear goals or a reactionary rather than proactive approach) among your team. Reflect on how your early wins might be able to change behaviors related to those patterns. Other behavioral patterns that might require improvement include:

- Lack of discipline

- Lack of innovation

- Lack of teamwork

- Lack of urgency

However, it’s not enough to simply avoid low hanging fruit when identifying your early wins. Instead, use the following principles to ensure that you maximize the benefits of your chosen projects:

- Don’t become too scattered as you evaluate areas for implementing your early wins. Taking on too much early on will undermine the quality of your results later.

- Focus on wins that dovetail with your boss’s priorities. Remember the expectations conversation from Chapter 4? Use insight about your boss’s areas of interest and background to start highlighting possible early wins. Consider also which kind of early wins would most energize your direct reports and team.

- Achieve the wins in a way that sets a precedent for your team. Rather than using a quick approach that might be anathema to the company culture, use processes that set a tone for how you want your team to operate moving forward.

- Use STARS to identify appropriate wins. The early wins for a realignment might be less concrete and more focused on messaging or altering the vision. By contrast, a turnaround will likely demand concrete wins in technical or financial areas.

- Align your wins with the unique ways in which your company celebrates success. For example, if the company extols individual accomplishments, then it may be appropriate for you to take the lead on your early win. But if group victories are actively encouraged, you may want to build the early win with your team.

- Elevate the right team members by identifying who has the best background, attitude, and skill set to contribute to your early wins.

- Ask whether the potential project can be achieved in a short amount of time with the resources that are available.

Once you identify a possible early win project, consider whether it’s feasible and primed for success by using the FOGLAMP evaluation tool:

Focus: What are the parameters of the project?

Oversight: Who will be in charge of overseeing the project?

Goals: What are necessary check-points and timelines for reaching them?

Leadership: Who will take point on leading the project and are they sufficiently trained to do so?

Abilities: What assortment of team members is needed to ensure the necessary skills and backgrounds are included?

Means: What resources will you need access to?

Process: Are there specific models or structures that will lead to success? Does the team need to be trained on them?

Building Needed Credibility

Beyond thinking about what kind of wins you want to achieve, consider also how your leadership style and reputation might impact the way those early wins are perceived and whether they foster or undermine your overall credibility.

For example, you may be in a position similar to that of Elena, who was promoted to head of customer service for her retail company and suddenly found herself managing her former peers (managers of the company’s call centers). Elena set a tone early on by clearly communicating the goals for her new position, creating regular meetings for feedback with each call center manager, and making several thoughtful human resources changes. Because Elena took these key steps, she was able to secure various early wins in both improving customer satisfaction and cementing respect for her new authority.

If you also find yourself preparing to manage former peers, consider the following important principles for success:

- Accept early on that the contours of your relationship to former peers will have to change.

- Use formal and symbolic transition tools to render your new role concrete in the eyes of former peers (e.g., an official ceremony where your former boss passes the baton).

- Evaluate whether any team members will be so disappointed about not being promoted themselves that they cannot continue to effectively support the team.

- Strike a balance between over-exerting your authority to make a point and under-asserting yourself and thus not actually transitioning into the new role.

More generally, all leaders will need to navigate the complex task of building credibility in their new role. Even before you formally start in that role, opinions will begin to form about your style and approach. Once opinions ossify, they can be very hard to change. Indeed, the phenomenon known as “confirmation bias”—where people will focus on information that confirms what they already believe and will ignore any evidence to the contrary—can easily take hold during the first stages of a new job. For that reason, it’s essential to inform the optics of your brand early on. What a successful brand looks like will vary for every role, but some general leadership traits that can help foster credibility include:

- Being demanding but not impossible to please by setting realistic goals and holding people accountable while also celebrating and acknowledging successes

- Being approachable but with reasonable boundaries that acknowledge the nature of your role

- Being decisive but thoughtful because tough calls have to be made but don’t have to happen in a reactionary fashion

- Being focused but open to input

- Being proactive but not agitating. People need time and space to grow into change. Help set a sustainable pace for achieving new goals.

- Being tough but fair. As a leader, it falls on you to make hard decisions, but the way you do it—hopefully by preserving people’s dignity and humanity—won’t go unnoticed.

These traits can help inform a plan for how you want to introduce yourself to the company and your team. Different processes might support the dissemination of your unique brand. For example, one-on-one meetings with each direct report might be beneficial. Or maybe you’ll decide to travel to each office location to do introductions. Ultimately, however, if you are genuinely committed to learning about the ins and outs of the company, you are less likely to be perceived as a bulldog preparing to implement vast change without input and more likely to be seen as a thoughtful and engaged leader.

As you build your brand and engage in your learning process, keep an eye out for small “teachable moments” that allow you to create an example of how you will lead. These moments might be as simple as taking time to introduce yourself to the support staff or reacting calmly to small mistakes early on. Word will spread quickly about how you handle these seemingly insignificant encounters.

Implementation

Once you have (1) identified important areas for early wins that align with your long term goals and (2) started building the credibility necessary to achieve them, you’ll need to implement a process for success. Effective implementation of a new project will require the following five elements:

- Awareness of the project’s benefits

- Diagnosis of why this change needs to happen

- Vision for strategy moving forward

- Plan that is based on needed expertise

- Support from personnel needed to implement

It’s quite possible that you’ll be missing one of these components. But for each missing piece there is a corresponding action that you can take to resolve it. For example, if there is a:

- Lack of awareness of the project’s benefit—> Engage in collective learning about the problem (perhaps through exposure to new data or comparisons with competitors)

- Lack of diagnosis regarding why this change needs to happen—>Find tools to evaluate the root cause of the problem

- Lack of a vision for moving forward—> Bring the team together for a strategy session

- Lack of a plan that is based on needed expertise—>Prioritize the nuts and bolts of a plan

- Lack of support from personnel needed to implement—>Focus on coalition building (see chapter 8 for more on this).

While engaging in these steps may take time, this approach is preferable to forcing change from the top down and experiencing the negative repercussions later. However, in some circumstances (such as a turnaround), it may be less important to resolve the problems identified above because the need for change is stark, and the company is anxious to implement a plan.

Less concrete but just as important as the five elements referenced above will be recognizing if or when there is a lack of cultural support for the change that needs to be made. Changing a company’s culture can be very challenging and must be approached delicately so as to avoid a negative reaction from those attached to the status quo. Evaluate both the positive and negative aspects of the current culture and find ways to celebrate the former while also preparing to improve the latter.

Finally, as you move towards securing your early wins, beware any blind spots you have that could result in bombs going off which distract you and the team and undermine your hard work. Identify potential problematic areas early on by asking about:

- How the external environment (public opinion, economic conditions) might create challenges to achieving your goals

- How the competitive market might change in a way that undermines your success

- How internal gaps in skills or resources might impact your goals

- How organizational politics might present hurdles or landmines to enacting change

Building Alliances

As you plan your early wins, consider who you’ll need in your corner to achieve them. Remember also that having an alliance doesn’t mean having unanimous support. Focus on who you really need to get on board and allocate your time and energy there. Identify early on where you might face push back or blockage—include a strategy for winning those people over in your plan. Below are the steps to take in order to effectively build your alliances.

In order to build your alliances, you’ll need to learn more about the landscape of your company.

Map Out the Players

Who do you need help from? What role do they play in achieving your objectives? At what stage will you need to get them on board? Consider creating a chart mapping out each of these players. After you have identified the various individuals with power in your company, evaluate which ones you need on board for each specific goal. What combination of these players would constitute a winning alliance? What constitutes a “blocking alliance”? Think proactively about why they might be opposed to your plan/agenda and how you can assuage their concerns.

Map Out the Networks

You should be thoughtful not only about who has the power to help or hurt, but also about how they make decisions and who influences them. Sometimes those channels of persuasion are informal but provide key insight into how information and decision making flows within the structure of the company. Identifying those channels may take time but consider the following options for gaining key insight sooner rather than later:

1. Notice how and where your business engages with outside actors such as other companies, suppliers, or various stakeholders. Such engagements will likely highlight key focal points where important members of your company come together.

2. Use both formal meetings and informal interactions as opportunities to identify power dynamics within and between teams. Who carries authority and who is trusted/respected to provide opinions and insight? People might have influence for different reasons, such as:

- Unique expertise

- Power over information

- Access to relationships

- Control over resources

- Personal loyalty

3. Look out for “power coalitions” which are sub groups that align to achieve certain goals or to protect certain interests. See if your agenda aligns with these groups, but be careful not to undermine your goals by getting caught in political tensions between distinct power coalitions.

Create a Diagram of Influence

A diagram can help you visualize how each of these pieces interact. Put your winning alliance at the center of the diagram and around the alliance note other individuals with power. Use arrows to indicate how those individuals might exert influence over your winning alliance.

Within these network diagrams you can also begin to code for people who support, oppose, or are undecided on your goals by highlighting them with different colors. A few things to consider as you categorize individuals on your map:

1. Supporters should not be taken for granted. You should regularly engage them to confirm and deepen their buy-in.

2. Remember that supporters may also come from surprising places. Perhaps you disagree with an individual in other areas but you share interests regarding one particular goal—alliances of convenience can be beneficial for everyone. Don’t discount anyone and think capaciously about who you can bring on board.

3. If you are trying to identify more supporters, consider people who (1) have a similar vision for the company as you, (2) are also new, or (3) generally have a reputation for being open-minded or creative thinkers.

4. Never assume someone will oppose you and always seek to understand the basis for opposition so that you can identify any possible effective counter arguments. Converting someone from being opposed to being on board could set a powerful tone. Consider also how can you help someone meet their goals down the road if they jump on board with you now? Some common reasons individuals may be opposed to change are:

- Concern that disrupting the status quo will undermine what they have come to know and rely on

- Insecurity that they will be less important or effective if changes occur

- Perceiving change as a threat to the culture or core values they identify with

- Worrying about the impact change might have on their own authority and/or the possible negative attendant consequences to others in their corner or alliance

5. In between the supporters and the opposition are the persuadables. Perhaps they are agnostic, not yet informed, or waiting to decide. Here you have an opportunity to:

- Tip them over the indifference edge by offering your support in another area of value to them

- Provide them with necessary information/education to make a favorable choice

- Build momentum so that folks waiting to join the winning team choose you.

Your networking map might be quite expansive. Accordingly, it’s important to allocate your energy efficiently and to prioritize engaging with the most pivotal people. Evaluate what fundamentally motivates those individuals (recognition, power, personal growth, and so on). Consider also what internal and external pressures they are subject to. Are there driving forces that align with your own? Or are there situational reasons that are restraining their ability or desire to get on board? Don’t just assume that someone is opposed because they are self-interested or uncooperative. Evaluate the context in which they operate to see if there is anything you can influence or change. Also consider whether opposition may be grounded in concerns about effective implementation. Is there a way you can do a test round? Or slowly build confidence?

Exert Your Influence

Now that you know who to focus on, you can employ distinct tools to effectively exert your influence. Examples include:

Consultation: Solicit feedback about your plan and engage authentically with concerns that may arise. Reflect back points that people have made so that they feel heard and valued in the process.

Framing: Approach your framing of the issue on an individualized basis. Each conversation should be informed by that individual’s particular background, position, and style. For example, some people might respond well to arguments grounded in hard data and facts (logical or “logos” arguments). Other people might be moved by a framing related to key principles and values (ethos driven arguments). Or, finally, you might want to tap into emotional motivators such as an inspiring vision (pathos arguments).

Choice-shaping: Think about ways you can affect how people perceive their alternatives. For example, if people are worried that your project will be too expansive or will set a bad precedent, consider explaining how it will be circumscribed in order to avoid creating a slippery slope. Propositions that are perceived as win-lose are tricky to sell. Evaluate how you might be able to create more nuance around the issue so that there are more opportunities for others to see the benefits.

Social influence: We care about the opinions of others that we respect. Is there a key person you can get on board first who will then be influential to the decision-making process of others? Consider also that people like to make choices that are consistent with their values and belief systems, uphold their prior commitments, repay obligations, and preserve their image/reputation.

Incrementalism: People are less likely to be scared off by change if it’s viewed in small approachable steps. How can you map out those steps for them? A good place to start might be by engaging in a team-wide diagnostic activity. The more people agree on the problem, the more likely they are to commit to work towards a step-by-step solution.

Sequencing: Be strategic about the order in which you bring different individuals on board. Allocating energy on the front-end to convincing one integral ally could be key to building momentum towards greater coalition building.

Action-forcing events: Scheduling meetings and creating deadlines can help prevent stalling or avoidance that may be undermining progress and ultimate success. Psychologically, these concrete check-points will also create momentum and build accountability for people to commit to next steps.

Ultimately, the most important thing to remember is that alliances will be needed when implementing any changes. If you jump towards proposed changes and solutions without simultaneously doing the work to bring necessary actors on board, your efforts may well be fruitless.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Michael Watkins's "The First 90 Days" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The First 90 Days summary :

- A field guide for anyone undergoing professional transition

- How to develop strong relationships with your new colleagues

- Why early wins are so important