This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Design of Everyday Things" by Don Norman. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

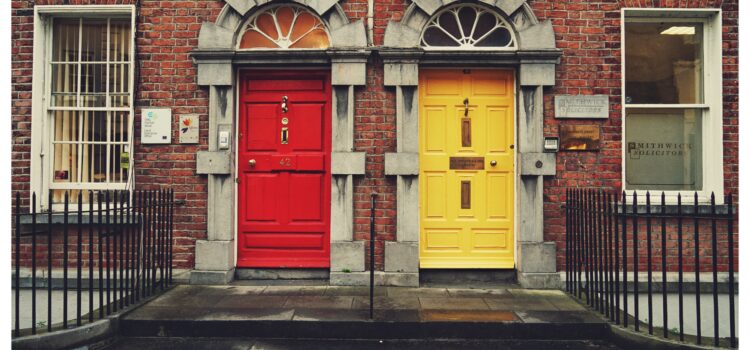

What does design in the real world look like? How does design thinking manifest in the objects you use in everyday life?

You might not realize it, but you interact with design in the real world every day. Everything from doorknobs to your smartphone has been designed.

Read more about design in the real world and how it works.

Design in the Real World

Human-centered design has become a buzzword, and even well-intentioned companies often fall short of the ideals. Pushing a product through a lengthy iterative design process that involves weeks of field observations is a great idea in theory, but in practice, budget and time constraints play a much bigger role. This is why the author proposes his own eponymous “Law of Product Development”: that all product development projects are “behind schedule and above budget” from the moment they start.

What Makes the Design Process Difficult?

Beyond time and budget, the makeup of the product development team can present difficulties. The best teams are multidisciplinary, combining unique knowledge from different specialties and from every phase of the product development process. The downside of this arrangement is that every team member typically thinks their own discipline is the most important. To manage this, it’s important for teams to reach a mutual understanding of each other’s strengths and needs, and why those needs are important for the overall success of the product.

Strong management is crucial to prevent individual departments from making independent changes to the design in the real world, but getting everyone on the same page takes time. To streamline the process, Norman recommends having the design research and market research teams working in the field consistently, even before there is a specific product to be tested. This gives the entire team a head start with a solid foundation of user needs and motivations that can be honed through the rest of product development.

Designing for Special Populations

Another hurdle in the design process is conflicting product requirements. Designing a single product that satisfies all members of the product development team and meets the needs of a diverse group of users is a tall order.

One tool for designing to suit as many users as possible, despite the wide range of human needs and traits, is physical anthropometry. This field studies measurements of the human body, both at rest and while performing specific tasks (like range of motion for reaching behind you). These standardized measurements allow designers to work within percentiles, ensuring that the final product is likely to work for as many users as possible. But no one design in the real world works for everyone, and even the most inclusive designs can be unusable for tens of millions of users.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Don Norman's "The Design of Everyday Things" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Design of Everyday Things summary :

- How psychology plays a part in the design of objects you encounter daily

- Why pushing a door that was meant to be pulled isn't your fault

- How bad design leads to more human errors