This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions" by Thomas Kuhn. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is Thomas Kuhn’s philosophy of science? How did his ideas revolutionize the way scientists think about the development of science?

The central tenet of Kuhn’s philosophy of science is the distinction between normal and revolutionary science. Normal science is a progressively cumulative compendium of knowledge within the established paradigms. Revolutionary science happens when there is a shift from the set paradigm.

Read more to learn about Thomas Kuhn’s philosophy of science.

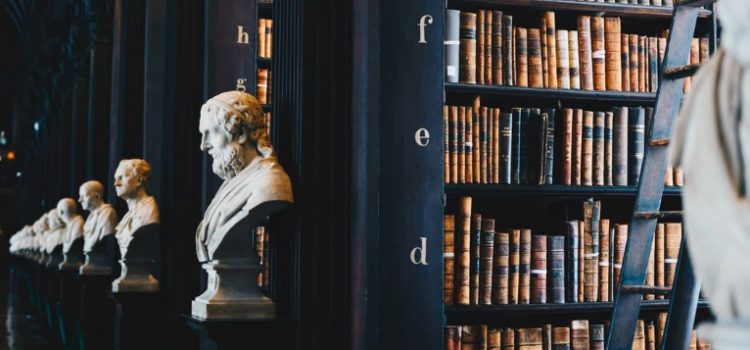

Overview of Thomas Kuhn’s Philosophy of Science

Thomas Kuhn’s philosophy of science is premised on the notion that there are two types of science: normal science and revolutionary science.

Normal science is our conventional view of science as cumulative: new ideas are piled on top of old ones to increase the overall knowledge that we have. Normal science doesn’t try to find new theories or explanations for things. In fact, new information that doesn’t fit the paradigm is usually ignored or brushed aside completely. However, that’s not to say that normal science should be disparaged. While the paradigm hugely reduces the scope of normal science, it allows the depth of study that’s key to advancing science.

Scientific revolutions, on the other hand, aren’t about moving closer to the truth—they’re about moving away from old ideas that don’t hold up anymore. Revolutionary science happens when scientists discover an anomaly that cannot be explained within the existing disciplinary frameworks.

In attempting to resolve the anomaly, scientists will push the rules of their current paradigm as far as they can go in an effort to see exactly where they break down. Once the breaking point is found, they will start speculating about new theories that can explain the anomaly. If one of those theories holds up under scrutiny, it may form the basis of a new paradigm.

However, for a new paradigm to take over, the old paradigm must first be rejected. The process of rejecting a paradigm doesn’t just involve comparing it with nature, but comparing it with another paradigm.

This is usually resolved in one of three ways.

- The first possible outcome is that normal science finds a solution to the anomaly after all, and the field returns to its pre-crisis state.

- The second possible outcome is that the anomaly is not resolved; however, scientists still believe that it is solvable. In this case, the issue is set aside for future generations to figure out.

- The third is that a new possible paradigm emerges and the two struggle for dominance in the field. If a new paradigm wins that struggle, it becomes a scientific revolution.

Paradigms must be based on theories. Scientific history shows that many competing theories can explain the same sets of data. Even so, normal science makes no effort to develop new theories, because there is no need for them as long as the current paradigm holds. That’s exactly why anomalies are so important to scientific advancement: They are the stimulus for scientists to break the rules and start looking outside of their paradigm for new ideas.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Thomas Kuhn's "The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions summary :

- How scientific paradigms evolve and become replaced with new paradigms

- Why science is more about figuring out what isn't right

- How throwing out past achievements allows for scientific progress