This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Against Empathy" by Paul Bloom. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s the difference between understanding someone’s emotions and actually feeling their emotions? Why is it important to make this distinction?

In his contrarian book Against Empathy, psychologist Paul Bloom differentiates between two types of empathy that equip us with distinct ways of caring about other people: cognitive empathy and emotional empathy. This distinction is critical for his argument against empathy.

Read more to learn about cognitive empathy vs. emotional empathy.

Cognitive Empathy vs. Emotional Empathy

In defining empathy and sketching out his case against it, Bloom characterizes “emotional empathy” and “cognitive empathy” as two distinct internal experiences. He writes that some neuroscientists believe that the brain actually uses two different systems for these processes, one that allows us to feel someone else’s feelings and another that allows us to understand someone else’s feelings.

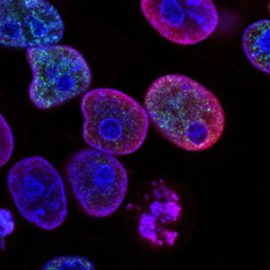

It’s important to understand cognitive empathy vs. emotional empathy in order to grasp Bloom’s position. The kind of empathy that Bloom argues against throughout the book is emotional empathy. Emotional empathy involves feeling someone else’s emotions and simulating their experiences. This ability is thought to draw on neural systems like mirror neurons: brain cells that activate both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else perform it. Some researchers think mirror neurons represent the neural starting point of empathy.

(Shortform note: Though mirror neurons have received a lot of attention, cognitive neuroscientist Christian Jarrett notes that many claims about these brain cells—including that they’re responsible for empathy, language, and culture—aren’t yet backed by research. He also argues that mirror neurons are likely part of a complex network of brain activity that gives rise to the experience of empathy.)

Cognitive empathy entails a more distanced appreciation of someone else’s experiences. Also called “mentalizing” or “theory of mind,” cognitive empathy involves understanding the emotions someone else is experiencing without experiencing them yourself. Bloom doesn’t oppose the use of cognitive empathy. In fact, he suggests that we need to understand others’ experiences to make morally good decisions, and cognitive empathy helps us do that.

(Shortform note: Experts explain that cognitive empathy or theory of mind enables you to recognize that other people’s thoughts and beliefs are different from yours. It’s called “theory of mind” because you can’t know what another person is thinking, but you develop ideas about their mental state anyway. For most people, theory of mind emerges early in child development and follows a predictable course that eventually helps us form accurate ideas about what others are thinking, though some argue there are differences in people with autism or schizophrenia.)

| Are Emotional Empathy and Cognitive Empathy Really Separate? The idea that emotional empathy and cognitive empathy are separate processes is controversial. A literature review that Bloom cites in the book comes to a different conclusion: The authors found that though early research suggested that two different groups of brain regions might underpin emotional and cognitive empathy, more recent studies suggest that these two types of empathy aren’t independent, but actually interact with each other. The review also explains that the parts of the brain that support empathizing and mentalizing often seem to be working at the same time, concluding that the best way to understand empathy isn’t to break it down into its constituent parts. Psychologist Kenneth Barish points out that researchers have proposed several ways of understanding empathy without dividing it into two separate systems. Some think of the emotional and cognitive components of empathy as layers of an experience, while others view empathy as a continuum of experiences from highly emotional to highly cognitive. Barish writes that these models correspond more closely to how we really experience empathy: as a combination of cognitive and emotional elements. Additionally, though Bloom talks about cognitive and emotional empathy as the two types of empathy, some experts add a third: compassionate empathy, which helps you not only understand another person’s situation but also seek to improve it. For many experts, the ideal isn’t to prefer one type of empathy or the other (or to forgo one or the other). Instead, the goal is to experience them in a healthy balance. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Paul Bloom's "Against Empathy" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Against Empathy summary:

- How the conventional understanding of empathy gets it wrong

- How empathy can motivate us to act in unjust, irrational, and cruel ways

- Why we should practice rational compassion instead of empathy