This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Distracted Mind" by Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is The Distracted Mind about? What is the negative impact of technology on human brains?

In The Distracted Mind, Adam Gazzaley and Larry D. Rosen define the distracted mind and the ways that technology has exacerbated it. They also discuss their proposed strategies for alleviating this condition by taking steps to improve our brain’s cognitive control and by modifying our environment.

Read below for a brief overview of The Distracted Mind.

The Distracted Mind by Adam Gazzaley and Larry D. Rosen

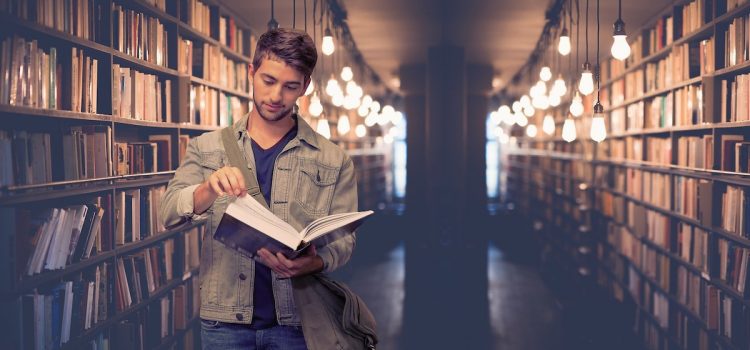

With a vast ensemble of screens, such as smartphones, laptops, and tablets, always at our fingertips, technology has infiltrated every aspect of our lives. And although this technological boom has delivered exponentially greater access to information, this access ultimately harms our productivity and ability to fulfill our goals, according to neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley and psychologist Larry D. Rosen. In their 2017 book The Distracted Mind, Gazzaley and Rosen argue that technology has made us significantly more prone to distractions and interruptions, hampering our higher-level cognitive goals and exacerbating what they call “the distracted mind.”

Gazzaley and Rosen’s backgrounds shape different aspects of The Distracted Mind. On one hand, Gazzaley’s experience as the founder of Neuroscape—a neuroscience center exploring the relationship between our brains and technology—informs his discussion of the neural mechanisms underlying the distracted mind. On the other, Rosen’s experience as the author of iDisorder, a best seller distilling years of research on the psychology of technology, proves invaluable in discussing the psychological aspect of technology usage. Additionally, both Gazzaley and Rosen are distinguished academics and have condensed years of their academic work into The Distracted Mind.

The Basics of the Distracted Mind

To begin, we’ll discuss the distracted mind itself to understand Gazzaley and Rosen’s later arguments about technology’s impact on it. In particular, we’ll start by analyzing Gazzaley and Rosen’s definition of the distracted mind as an ingrained vulnerability to distractions and interruptions. Afterward, we’ll discuss their thesis about the origin of this vulnerability—namely, that it arose because our higher-level goals outstripped our cognitive control, the faculties that we use to fulfill these goals.

Defining the Distracted Mind

To understand Gazzaley and Rosen’s later arguments about the distracted mind, it’ll help to understand what the distracted mind is to begin with. Put simply, they define the distracted mind as our susceptibility to interference that hinders our ability to achieve our goals.

At a broad level, Gazzaley and Rosen consider interference to be anything that disrupts your attempt to fulfill a specific goal. For example, imagine that you want to make your morning coffee, so you decide to grind some coffee beans. If, during this process, you receive an email notification that you stop to read, that would be a form of interference.

More narrowly, they assert that interference can come in the form of distractions or interruptions. On the one hand, distractions refer to irrelevant stimuli or information that catch our attention unintentionally. For instance, if you’re driving to work in the morning but have your attention temporarily diverted by a flashy car and miss your exit, that constitutes a distraction.

On the other hand, interruptions are intentional decisions to pursue a secondary goal that detracts from your primary goal. Returning to the previous example, if you consciously decided to stop and grab donuts on your way to work, that would count as an interruption rather than a distraction.

How Cognitive Control Limitations Make Us Susceptible to Interference

Having seen what it means to be vulnerable to interference, we can now discuss the origins of this weakness. Gazzaley and Rosen argue that we’re susceptible to interference because our cognitive control—the group of faculties that allow us to fulfill our goals—has limitations that make us susceptible to interference. To show as much, they examine these three faculties (attention, working memory, and goal management) to highlight their shortcomings.

Technology’s Impact on Interference

Now that we’ve covered what interference is and why we’re so vulnerable to it, we can discuss the ways that technology has exacerbated this vulnerability. More precisely, we’ll examine Gazzaley and Rosen’s argument that the Information Age increased our susceptibility to interference, their explanation for this increase, and finally, their warnings about the harmful effects of this uptick in interference.

Interference in the Information Age

Although Gazzaley and Rosen contend that our vulnerability to interference is a longstanding feature of human nature, they argue that it’s been exacerbated by modern technology. In particular, they argue that the Information Age made us more vulnerable to interference by creating information outlets that constantly vie for our attention. To show as much, they first outline how the Information Age increased potential sources of interference and then argue that this new interference has infiltrated our schools and workplaces.

The Information Age, Gazzaley and Rosen argue, began with the onset of the internet around 1990, as information previously only available via encyclopedias became much more accessible. Moreover, the authors point out that the internet led directly to email, which allowed us to communicate instantly with any other internet user.

Additionally, the authors argue that two further developments defined the Information Age—social media and the smartphone. First, social media enhanced email’s capacity for communication; whereas before, we could communicate with one person instantly, social media allowed us to communicate with millions of people instantly. Then, with the development of smartphones, we gained access to information from the internet and social media regardless of our location.

The upshot is that interference became exponentially more common as new sources of information—such as email alerts, text messages, and Twitter notifications—began to vie for our attention. Whether in the form of distractions, like the sudden “ding” of a text message, or interruptions, like actively choosing to check social media while at work, we became exposed to interference at every corner.

Why Does Technology Make Interference More Common?

Having discussed how technology increases interference, we’ll now examine Gazzaley and Rosen’s explanation for this phenomenon. Broadly speaking, they argue that technology leads to widespread interference because we’re evolutionarily wired to consume information, and technology provides easy access to such information.

To explain why our drive for information makes us more susceptible to interference, the authors first discuss the marginal value theorem (MVT)—a theory that predicts when animals will shift from one food patch to another to maximize food consumption—and then suggest that its insights can be applied to our information consumption.

The Harmful Effects of Increased Technological Interference

Now that we’ve seen how and why technology aggravates our distracted minds, it’s time to discuss the impact of this increased technological interference. According to Gazzaley and Rosen, technological interference does widespread harm in various domains of life, including school, the workplace, and our relationships.

How to Become More Resistant to Interference

Having shown the detrimental effects of interference, Gazzaley and Rosen next turn to potential remedies. Although there are no foolproof cures, Gazzaley and Rosen contend that we can minimize our susceptibility to interference by taking steps to improve our cognitive control and minimize potential sources of interference.

Strategy #1: Improve the Brain’s Cognitive Control

In light of their earlier claim that we’re susceptible to interference because of cognitive control limitations, Gazzaley and Rosen reason that one way to improve this condition is to improve our cognitive control. Although they consider various activities to strengthen our cognitive control, we’ll focus on the four that they contend have the strongest empirical support: physical exercise, meditation, cognitive exercise, and certain video games. Of these four, they note that only physical exercise rises to the level of a prescriptive recommendation, while the other three have comparatively less empirical support.

Strategy #2: Change Your Environment

Although Gazzaley and Rosen are optimistic that we can become more resistant to interference by improving our cognitive control, they argue that we can also combat interference by addressing the root causes according to the MVT—increased accessibility of information as well as increased anxiety and boredom when focusing on one information source.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen's "The Distracted Mind" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Distracted Mind summary:

- How technology has made us more prone to distractions and interruptions

- How to modify your environment to reduce distractions and boredom

- How to minimize your susceptibility to interference and improve cognitive control