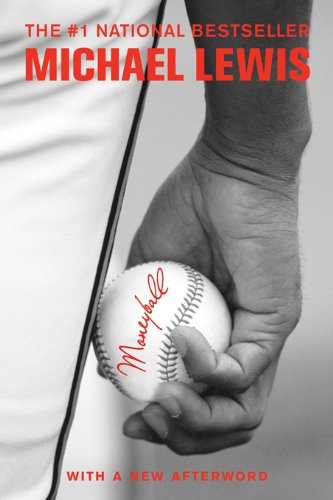

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Moneyball" by Michael Lewis. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Who is Scott Hatteberg in Moneyball? What did Scott Hatteberg do in Moneyball, and why was he important to the Oakland A’s winning strategy?

Scott Hatteberg was a Moneyball character and real-life professional baseball player. He was recruited by Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s as a part of their data-driven strategy.

Scott Hatteberg’s Moneyball Value

Before the start of the season, Paul DePodesta calculates that it will take about 95 wins to reach the playoffs in 2002. With this as the end goal, it’s then a matter of working backwards: to achieve 95 wins, they will need to have a runs scored vs. runs allowed differential of +135 (Bill James had discovered that there is a stable ratio between run differential and wins).

And this is where the team’s data-driven approach really pays dividends. The loss of Isringhausen, Damon, and Giambi definitely costs the team, but it costs them in a way that can be measured and quantified. If these players’ contributions to the positive run differential is now gone, they must find the players who, based on past performance, will be able to fill in those gaps. Such players don’t need to be highly paid stars, they just need to contribute to the team’s net run total. And such players can be had for very little, thanks to the irrationalities of the labor market for baseball players. For Scott Hatteberg, Moneyball is an opportunity.

Scott Hatteberg: A Diamond in the Rough

The final player acquired to replace Giambi’s offense, Scott Hatteberg, goes to the locker room after the loss to the Yankees to review the tape of the game. This is one of the qualities the team most admires about Hatteberg: he is a smart, analytical player, a student of the game who wishes to learn from his mistakes.

Once a catcher in the Boston Red Sox organization, with some hitting ability, injuries have robbed Hatteberg of his ability to throw the ball. As a result, his market value rapidly declines, and he struggles to find a major league team willing to take a chance on him after his contract expires in 2001. But, as we’ve seen with other players, Billy Beane’s Oakland A’s see upside in Hatteberg where other organizations see only downside.

For Hatteberg is also a remarkably disciplined hitter, with an uncanny ability to draw walks and get on-base. His mediocre .270 batting average conceals his true value. Because of his injury history and his unrecognized offensive contributions, Beane is able to sign Hatteberg for a mere $1 million.

No longer able to throw, Hatteberg is re-molded into a first baseman by Oakland. Although he struggles in his new role during 2002 spring training, by mid-season, he blossoms into an above-average first baseman. But that is just a bonus for the organization. Billy Beane has not brought Scott Hatteberg to Oakland for his fielding ability—Scott Hatteberg’s Moneyball role is to go to Oakland to hit.

Hatteberg is the opposite of what Billy Beane had been as a player. Where Billy was petrified of striking out (which caused him to madly swing at every pitch), Hatteberg is unafraid of the third strike. He has the patience and discipline to wear out opposing pitchers, forcing them to throw inferior pitches which he can then hit. He knows how to wait for the game to come to him, rather than trying to force the game to bend to his desires. In short, he has the mental durability that Billy Beane had never developed as a player. This means Scott Hatteberg in Moneyball is the ideal kind of player; he’s disciplined, and he creates opportunities to score runs.

Oakland is the ideal environment for a player like Hatteberg to thrive. The Red Sox had scorned his thoughtful approach to hitting as weak and passive. They wanted hitters with flash and power, even if these hitters also struck out on the regular. The team would yell at him for drawing a walk with a man on base, foolishly labeling such behavior as “selfish.” They had wanted him to swing at everything. The Boston hitting coach, Jim Rice, even derided Hatteberg for working the count and grinding pitchers down, pointing out that Hatteberg had a .500 batting average when he swung at the first pitch. Of course, Hatteberg would only swing at the first pitch when it was too good to not swing at, which was rarely the case. Still, the Red Sox organization would not hear of it and tried to force Hatteberg to become a slugger.

But everything is different in Oakland. Hatteberg’s style blends perfectly with Beane’s philosophy and he thrives. By the end of the 2002 season, Hatteberg is one of the stingiest swingers in the league, choosing not to swing at 64.5 percent of pitches thrown to him—the third-highest rate in the American League. DePodesta calculates that if Scott Hatteberg had taken every at bat for the A’s in 2002, the team would have scored between 940 and 950 runs, more than the entire roster of the powerhouse Yankees. Put another way, nine Scott Hattebergs are worth more than the entire Yankee team. Scott Hatteberg in Moneyball proved his value.

Scott Hatteberg’s Moneyball role is essential in making the team successful. Hatteberg, previously overlooked despite his high on-base percentage, helped make the Moneyball strategy work for the Oakland A’s.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Michael Lewis's "Moneyball" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Moneyball summary :

- How Billy Beane first flamed out as a baseball player before becoming a general manager

- The unconventional methods the Athletics used to recruit undervalued players

- How Sabermetrics influences American baseball today