This article gives you a glimpse of what you can learn with Shortform. Shortform has the world’s best guides to 1000+ nonfiction books, plus other resources to help you accelerate your learning.

Want to learn faster and get smarter? Sign up for a free trial here .

What do all outstanding parents have in common? What qualities of a good parent are essential for children’s development?

If you’re a new parent, you might feel terrified that you’re going to fail your child. Making mistakes is part of the process, but, if you possess these five qualities, then your child will be more likely to grow up healthy and happy.

Let’s look at the five qualities of a good parent and how to exhibit them in your everyday life.

1. Communication

Communication is one of the top qualities of a good parent. Having conversations with your child will encourage them to cooperate, lead to fewer arguments, and make your interactions less stressful and more enjoyable. Once you establish this virtuous cycle, it will pay off for years. How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk by Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish will help your family communicate more effectively.

How to Deliver Empowering Praise

Faber and Mazlish explain that giving empowering praise is a great way to start effectively communicating with your children. They emphasize praise for several reasons. First, praising your child is something proactive that parents can do at any time. It ensures you’re communicating, not just about problems that need to be addressed, but also about what you’re proud of. Finally, it’s a powerful way to encourage positive behavior.

To deliver effective praise, though, Faber and Mazlish say you must first understand what not to do. As they learned from the child psychologist Haim Ginott, praise is like emotional medicine and should be administered carefully and intentionally. When your children ask you if their scribbled drawing is “good,” you may reply, “Yes! It’s great!” But this kind of praise doesn’t sound authentic to kids because it’s too vague and doesn’t show that you’re paying attention and appreciating what they’ve done.

Now, here’s what Faber and Mazlish recommend instead:

- Use descriptive praise. Specifically and enthusiastically describe what you see in their drawings, such as the shapes and colors. Your children will appreciate that you’re paying attention. Descriptive praise also makes children aware of their strengths and builds their self-esteem. They can then praise themselves.

- Find a positive label. Faber and Mazlish say you should give your child the language for the qualities you’d like to see them develop. For example, notice when a child is trying hard to complete a task and tell them they’re working hard or showing perseverance and determination. If they stand by a friend who’s being teased, tell them they showed friendship, loyalty, or courage.

How to Respond to Negative Reactions

Faber and Mazlish stress that, in addition to praise, a second key to communicating better with your child is to show that you understand, accept, and empathize with their feelings. Children, even babies, want adults to understand how they feel, especially when they feel unhappy.

But, as with praise, how you respond is important. First, here’s what not to do when your child expresses strong feelings, according to the authors. Don’t deny a child’s feelings by saying something like “You’re just tired,” “You don’t really hate your brother,” or “You can’t be hungry! You just ate.” Don’t just tell them, “It’s not a big deal. Calm down” or “You’re not acting your age.”

Instead, Faber and Mazlish recommend giving your child words for their feelings. Just as you do with praise, you should be descriptive when talking about negative feelings. Don’t worry that telling a child they’re “afraid,” “sad,” or “disappointed” will make them feel worse. Having their feelings acknowledged will help them feel understood and help them build a vocabulary for their emotions, the authors say.

2. Patience

Children are extremely sensitive to their parents’ emotional states. If you keep calm, it’s more likely that your child will, which is why patience is another important quality of a good parent. Stress causes parents to discipline their kids more severely and more inconsistently, which is exactly what you’re trying to avoid.

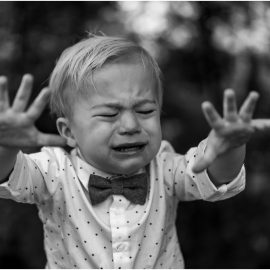

Unconditional Parenting by Alfie Kohn and Good Inside by Becky Kennedy recognize that staying calm can be a particular challenge if you’re in public or if a child shouts things like “I hate you!” or “You’re a bad daddy!” In these cases, don’t get flustered; just see this as a way that they’re expressing negative feelings at the moment. If you stay calm and show patience, you’re also modeling good emotional regulation, which is one of the most important life skills your child can learn.

Some kids feel their emotions more intensely than others, and as a result have more intense reactions: their tantrums, for example, are more frequent, challenging, and easier to spark than other children’s. This is compounded by the fact that these children also notice the comparative intensity of their feelings and reactions, and they fear that they’re unloveable and that their parents won’t be able to deal with them. This fills them with shame and fear, which only serves to make their reactions harsher and make it harder for parents to find ways to approach them.

Kennedy argues that a child with intense emotions and reactions fears that her outbursts will be too much for others to deal with. By calmly approaching discipline and taking your time to understand their needs, you’re showing your child that their reactions aren’t too much for you to deal with.

What if their reactions are too much for you to deal with? Take them to a safe place where they won’t hurt themselves or anyone else, and then let them know that you need to take some calming breaths but that you’ll stay close by and come back soon. Step away, collect yourself, and come back when you’re ready.

3. Listening

Being a sympathetic listener, according to 1-2-3 Magic by Thomas W. Phelan, is a must-have quality of a good parent. Listening shows your child that you’re trying to see things from their point of view. Seek to understand the way they experienced a situation, and then relay your understanding back to them to make sure you got it right.

Sympathetic listening often begins with a simple, open-ended question or comment from you. For instance, “You looked a little frustrated when you got in the car after school today.” If the conversation stagnates or you need more clarification, you can add non-confrontational comments or questions, like “Did it upset you when Johnny ruined your artwork?” or “Why do you think Johnny would do something like that?” With each comment or question, your goal is to deepen your understanding, not to teach a lesson or draw your own conclusions.

Sympathetic listening is often more easily said than done because it requires a great deal of parental self-control. As Phelan explains, there’s no place for parental judgment or opinion in sympathetic listening. So, even if you’re disappointed or angry about how your child handled something, you need to stay focused on understanding their perspective rather than launching into a lecture about how they should have known better or providing your ideas for how to solve the problem or make amends.

There are many benefits of sympathetic listening. One is that it can help kids process and thus let go of negative emotions. When you communicate to your child that you understand why they were feeling upset, it honors their feelings about a situation, even if you’re not a fan of their actions. Another benefit is that compassionate listening can help you avoid being an overbearing parent. When you refrain from lecturing, judging, and problem-solving for your child, you’re helping them build their self-esteem by showing them you trust them to independently handle setbacks and make good decisions.

Listening in Children and Further Advice on Posing Questions

The authors of Difficult Conversations argue that listening well to someone makes it likelier that they’ll listen compassionately to you in return. So, by making this effort to understand and verbalize what your child’s going through, you might increase the chances of your child giving you the same understanding in the future.

The authors also provide advice to guide your questioning: Avoid masking a statement as a question. If you do this, your child might perceive you as being snide and won’t want to engage. For instance, asking, “Are you upset?” if your child is openly crying might come across as condescending or willfully blind. Instead, it would be better to simply state, “You seem really upset. Want to talk about it?”

4. Playfulness

Playfulness is not only an important quality of a good parent, but it’s a fun one. Parents should encourage and display play when interacting with their children. Children are constantly learning by watching and listening, but they also learn by doing—including playing.

According to The Gardener and the Carpenter by Alison Gopnik, biologists define play as having the following five characteristics: 1) Play is not work, 2) Play is fun, 3) Play is voluntary, 4) Play requires a safe and secure environment, and 5) Play relies on a pattern that includes repetition and variation. Because it’s child-directed, play is one of the most important ways that children guide their own development—if you try to force a child to play, direct how they play, or control the outcome of their play, it’s no longer play by definition. Instead, we should create environments that allow children to play, thereby supporting their natural growth.

While many animal species play in different ways, such as playing with objects or play-fighting with each other, human children may be the only species that play by pretending. Children begin pretending at just one year old. Contrary to what many believe, children don’t have trouble distinguishing between fact and fiction—they know what they’re pretending isn’t real. They do it to learn and have fun.

Gopnik suggests that pretending is a way for children to practice hypothetical or counterfactual thinking, which is the ability to imagine possibilities beyond what’s currently real. This is the skill that allows us to change both our thinking and the world itself because it lets us realize that our current knowledge or way of thinking could be wrong and imagine how things could be different.

Reading fiction to your children can assist in counterfactual thinking and has some of the same benefits as pretending. Both activities allow children to take on the perspectives of others, and the benefits of reading don’t end in childhood. Adults who read a lot of fiction—particularly literary fiction—are more empathetic and have a better understanding of others’ perspectives than people who don’t read as much fiction.

5. Self-Reflection

The last quality of a good parent that we’ll discuss is the active reflection and assessment of your life when you’re feeling overwhelmed. The longer you live, the more memories you acquire, and the greater the potential for unintegrated implicit memories to influence your day-to-day life. According to The Whole-Brain Child by Daniel J. Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson, all adults need to identify and integrate unprocessed memories, but the stakes are higher for parents, because:

- Children can sense their parents’ emotions. You may be smiling and playing with your child, and she can still pick up on your underlying stress or fear—even if you’re not consciously aware that you’re feeling that way. It’s difficult for your child to feel happy or at ease when you’re upset.

- Implicit memories can trigger emotions that negatively affect how you interact with your child. Your child may say or do something that triggers you to lash out, overreact, or withdraw.

If you notice yourself reacting in a way that doesn’t suit the situation, reflect on your behavior. First, check in with yourself, as you would with your child: Are you overly tired, hungry, or upset about something else? Then, if those factors don’t entirely explain your feelings and behavior, consider whether an implicit memory is affecting you.

Ask yourself if this situation is reminding you of something in your past. Reflect upon your own childhood, your relationship with your parents, and other memories that may be pertinent. If you hit upon something, journal, think through the memory, or tell the story to someone. This process will free you from the memory so that you don’t bring that baggage into your relationship with your child.

The goal isn’t to be overly self-critical, as that doesn’t help either; it’s to introduce a healthy level of humility and an openness to change.

Wrapping Up

Like children, every parent is different. Your parenting style might not be the same as anyone else’s. But, generally speaking, everyone who has a child possesses these five qualities of a good parent. All it takes is a mindful application of these traits in your relationship with your child.

This list is by no means exhaustive. What are other important qualities of a good parent? Let us know in the comments below!

Want to fast-track your learning? With Shortform, you’ll gain insights you won't find anywhere else .

Here's what you’ll get when you sign up for Shortform :

- Complicated ideas explained in simple and concise ways

- Smart analysis that connects what you’re reading to other key concepts

- Writing with zero fluff because we know how important your time is