This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Why We Sleep" by Matthew Walker. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are the psychological effects of sleep deprivation? How can they hurt you?

The psychological effects of sleep deprivation can be severe. You know that sleep has numerous benefits for the brain, but may not know the psychological effects of sleep deprivation, and how depriving someone of sleep can leave both short-term and long-lasting harm.

The Psychological Effects of Sleep Deprivation: How It Harms the Brain

While getting great sleep is good for the brain, sleep deprivation is unambiguously harmful for the brain. We’ll show damage in three ways: to attention, to emotion control, and for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Sleep Deprivation Worsens Attention and Concentration

One of the psychological effects of sleep deprivation is loss of attention and concentration. Sleep deficits are very bad for attention and concentration. This is especially harmful during high-risk activities, like driving.

Here are some ways to put the risk into perspective:

- Driving after having slept less than 4 hours increases crash risk by 11.5x.

- Being awake for 19 hours (being past your bedtime by 3 hours) is as cognitively impairing as being legally drunk.

- Adding alcohol to sleep deficits has a multiplicative effect on mistakes, not just an additive one.

Sleep deficits add up over time, and performance progressively worsens with greater sleep deficit. Having 10 nights of 6-hour sleep is equal in damage to one all-nighter, as is 6 nights of 4-hour sleep.

Why does sleep cause more accidents? Part of it is delayed reaction time. Another part is a “microsleep,” where your eyelids shut for just a few seconds and you go unconscious and lose motor control. If you’re in a car going 60 mph, falling asleep for just a few seconds could result in a terrible accident.

Sleep deprivation is an insidious problem because when you’re sleep deprived, you don’t know how poorly you’re performing. (This is like being drunk and thinking you’re far more capable of doing things than you actually are). And if you’re chronically sleep-deprived, your low performance becomes a new normal baseline, so it’s hard for you to see just how badly you’re performing.

Think you can do just fine on 6 hours of sleep? Chances are, you can’t. Less than 1% of the population is able to get six hours of sleep and show no impairment (this is largely genetic and relates to the BHLHE41 gene). Everyone else is just fooling themselves and propping up their energy with caffeine.

And think you can get by with power naps? They only get you partway there – power naps are most effective at the onset of fatigue, not when you’re already sleep deprived.

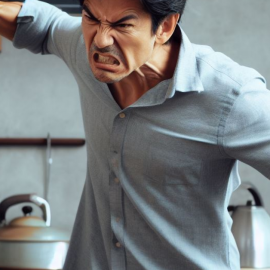

Sleep Deprivation Worsens Emotional Control

A baby that doesn’t get its nap time tends to get cranky. Adults are the same way. This is another of the major psychological effects of sleep deprivation.

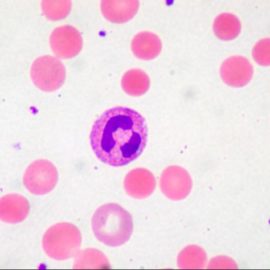

The amygdala is the part of your brain responsible for emotions like fear and anxiety. Normally, it’s held in check by your prefrontal cortex (the rational part of your brain). But when you’re sleep deprived, this suppression is weakened, and your amygdala can run amok, leading to 60% more emotional reactivity. The highs can be higher, and the lows lower.

On the other side of fear and anxiety, positive rewards and dopamine may be amplified by sleep deprivation too. Therefore, sleep deprivation can intensify sensation-seeking, risk-taking, and addiction.

More gravely, sleep may play an important role in mental illness. Here’s suggestive evidence:

- Sleep disruption is a common symptom of all mood disorders. The causation is unclear: does bad sleep cause mood disorders, or do mood disorders cause bad sleep, or both? But the author believes sleep plays at least some aggravating role.

- One night of sleep deprivation can trigger a manic or depressive episode in bipolar patients.

- Sleep deprivation is associated with suicidal ideation in teenagers.

- Surprisingly, sleep deprivation makes ⅓ of depression patients feel better, possibly by amplifying their positive emotions. However, it makes ⅔ feel worse, so it isn’t prescribed as a treatment. (though it would be interesting to preclassify the groups)

Why You Experience Psychological Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Now that you know about the psychological effects of sleep deprivation, you can consider all the positive benefits of getting great sleep, and why you need it.

Getting good sleep improves your brain in these ways:

Sleep Improves Memory

Your brain stories different memories in different places. The hippocampus stores short-term memory with a limited capacity; the cortex stores long-term memory in a large storage bank.

The slow-wave, pulsating NREM sleep moves facts from the hippocampus to the cortex. This has two positive effects: 1) it secure memories for the long term, and 2) it clears out short-term memory to make room for new information and improves future learning.

Have you ever woken up recalling facts that you couldn’t have recalled before sleeping? Sleep may make corrupted memories accessible again.

While good sleep improves memory, sleep deprivation can prevent new memories from being formed. This might be partially because the hippocampus becomes less functional with less sleep, partially because lack of NREM sleep prevents solidifying of new memories.

Unfortunately, making up a sleep deficit later doesn’t help recover a previous days’ memory – if you lost it, you’ve lost it.

2) Sleep prunes memories worth forgetting

Sleep doesn’t preserve all memories equally strongly – somehow, the brain knows which memories are useful and worth preserving, and which ones are useless and OK discarding.

Experimentally, this has been shown in experiments where subjects are given a list of words and instructed which words to remember and which to forget. Students who get to take a nap show stronger memories for the appropriate words, compared to students who don’t nap.

3) Sleep increases “muscle memory” or motor task proficiency

You might struggle with a motor task (like playing a tough sequence on piano), but after sleeping, be able to play it flawlessly. Sleep seems to transfer motor memories to subconscious habits.

Sleep deprivation also worsens general athletic performance: getting less sleep decreases your aerobic capacity, time to exhaustion, and recovery; and it increases risk of injury and lactic acid generation.

The above benefits generally occur in NREM sleep, which is concentrated in the beginning of sleep. In experiments, participants who have NREM sleep disrupted perform worse than those who have REM sleep disrupted.

A few last scientific details:

- Motor memory is associated with stage 2 NREM, which is concentrated in the last cycle of sleep.

- Sleep spindles are associated with better memory effects.

Now that we understand the impact of sleep on the brain, imagine how we can apply this knowledge into useful therapies:

- Imagine modifying sleep to selectively control what to remember from the day – like remembering content for an upcoming test and a happy moment, while decreasing traumatic moments.

- (This might lead to the side effect of having a have distorted memory of life).

- Use sleep to delete traumatic memories (for PTSD) or train away bad motor habits (like substance abuse).

- Find ways to augment the natural abilities of sleep, like with electrode stimulation of brain, pulsing sound in sync with brain waves, or rocking the bed rhythmically.

REM Sleep Has Major Psychological Effects

The psychological effects of sleep deprivation can affect your emotions, your thinking, and your memory. REM sleep has specific psychological benefits:

REM Sleep Blunts Emotional Pain from Memories

REM dreaming reduces pain from difficult emotional experiences. The brain seems to reprocess upsetting memories and emotional themes, retaining the useful lessons while blunting the visceral emotional pain. This might be why we can look back at painful memories without feeling the original full emotional intensity.

REM Sleep Increases Understanding of Other People’s Emotions

Sleep deprivation reduces your ability to interpret subtle facial expressions. Sleep-deprived people more often interpret faces as hostile and aggressive.

REM Sleep Increases Creativity

REM sleep creates novel associations between ideas, increasing creativity and problem-solving.

Informally, imagine the brain asking: “how can I connect what I’ve recently learned with what I already know, thus discovering insightful revelations? What have I done in the past that might be useful in solving this new problem?”

Thomas Edison knew the power of dreams. Reportedly, he would fall asleep holding metal ball bearings, releasing them just as he entered REM sleep. The noise would wake him up, just in time for him to write down his dreams before he forgot them.

These experiments showed a bevy of positive effects on creativity:

- REM sleep creates novel connections, between distantly related concepts

- REM sleep creates higher-level comprehension of ideas, finding the patterns among the noises

- REM sleep increases the ability to solve creative problems

- The content of REM sleep matters when solving that problem

The psychological effects of sleep deprivation should be taken seriously. Sleep deprivation can even cause death, but the long- and short-term psychological effects of sleep deprivation are also dangerous.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Matthew Walker's "Why We Sleep" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Why We Sleep summary :

- Why you need way more sleep than you're currently getting

- How your brain rejuvenates itself during sleep, and why nothing can substitute for sleep

- The 11-item checklist to get more restful sleep today