This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Origins of Political Order" by Francis Fukuyama. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How were societies originally structured? How and when were governments first formed?

In The Origins of Political Order, political economist Francis Fukuyama discusses the earliest social structures: families and tribes. He explains how their dynamics were an obstacle to the formation of states and thus influenced political development.

Continue reading to learn about the origins of government.

The Origins of Government

Fukuyama’s central goal is to explain the development of the state—by which he means a centrally organized institution that creates and enforces laws within a defined territory. Fukuyama says that, to fully understand the origins of government, we need to understand earlier social structures—namely, kinship bands and tribes.

(Shortform note: Arguably, a secondary goal of this book is to explain why humanity created states in the first place. As we’ll explore in more detail later—and as political theorists as diverse as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (The Social Contract) and Rutger Bregman (Humankind) agree—states are, in many ways, opposed to fundamental human social instincts.)

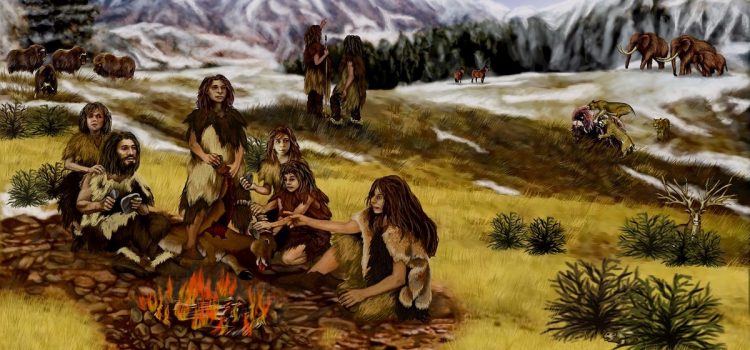

The First Societies: Kinship Bands

Fukuyama begins his account of political evolution tens of thousands of years before the first state by examining the earliest human societies. He does so because he believes that humans are fundamentally social and political and have always lived in cooperative social groups. (Shortform note: Contemporary science supports Fukuyama’s view that humans are social and political rather than individualistic—for example, neuroscience research suggests that the human brain is structured for social interaction, while some anthropologists argue that large-scale social cooperation is the defining feature of humans.)

Fukuyama says the earliest forms of organized society were kinship bands—nomadic groups of extended relatives who cooperated to obtain and share food, care for each other, and defend against predators and rival human groups. These groups were small (with no more than 30-50 members), and, because they were families, Fukuyama explains that there were no governments or rulers per se. Group leaders were chosen by consensus, and what power they had depended on the respect they commanded among their kin. If they lost that respect, they lost their power and their leadership position.

Also, Fukuyama says that, because these groups were nomadic, they had no formal laws. Instead, he says, these groups were governed by norms that promoted behaviors like sharing and cooperation that maximized the group’s chances of survival.

(Shortform note: While Fukuyama generally describes politics as an evolution away from these early kinship bands, some other authors suggest that band dynamics are still at play in contemporary life. For example, in Humankind, Rutger Bregman argues that our foraging ancestors were egalitarian and altruistic and that contemporary humans still share their fundamental desire for social cooperation. On the other end of the spectrum, in The Elephant in the Brain, Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson argue that social competition within kinship bands led us to evolve a talent for lying to ourselves and others—a tendency the authors believe explains much of modern life.)

The Invention of Agriculture Leads to Tribes

According to Fukuyama, once humans developed agriculture, they transitioned from kinship bands to tribes—larger, more loosely related groups tied to particular pieces of land. He explains that tribal society evolved from the need to govern and defend land. Whereas kinship bands were nomadic and thus had no concept of private property, tribal societies had a vested interest in protecting land they’d cultivated.

(Shortform note: In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari argues that agricultural life created the ideas of individualism and private property. He explains that whereas foraging bands lived, ate, and slept communally, tribal life saw the invention of homes, which for the first time separated individual nuclear families from the rest of the group and created a newfound sense of ownership and self-interest.)

Meanwhile, tribes grew much larger than kinship bands, though they remained organized around a sense of kinship. Fukuyama explains that religion in band and tribal societies consisted of ancestor worship, which (at the tribal level) created a sense of shared ancestral lineage. Because members of a tribe are all connected to that lineage (however distantly), societies could expand dramatically while retaining a sense of social cohesion that wasn’t possible in bands, which were structured around the immediate family.

(Shortform note: Fukuyama doesn’t say how large tribes were as compared to bands, but anthropologist Robin Dunbar estimates that tribes numbered between 500-2,500 members. Dunbar is best known for arguing that the human brain’s size limits our social networks to about 150 meaningful connections. This discrepancy between tribe size and our natural social capacity supports Fukuyama’s suggestion that humans need concepts—such as the concept of a shared ancestral lineage—to build and maintain large social structures.)

How States Overcame Kinship

According to Fukuyama, the biggest obstacles to state formation are the kinship ties that define tribal society. Lingering kinship loyalties align political officials with their familial groups rather than the central government and can lead to nepotism, patronage, and other practices that involve funneling resources toward one’s own community. To overcome this tendency, Fukuyama says, the state must break or avoid pre-existing kinship ties in order to secure loyalty to itself.

(Shortform note: The lingering tribalistic tendencies Fukuyama describes shouldn’t be mistaken for the polarized, antagonistic political behaviors that have also been described as “tribalism”. In fact, some commentators have argued that this latter usage is inaccurate and that tribal cultures enjoy peace and cooperation that’s unheard of in contemporary political partisanship. These commentators contend that actual tribes depend on a sense of social solidarity and “group feeling” that drives tribal politics toward compromise and tolerance—values they say could help repair the fractured political scene in many contemporary societies.)

One way to escape kinship ties is to impose an impersonal system of government such as a bureaucracy—organization around a permanent class of trained professional government employees. According to Fukuyama, the first state emerged in China during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BC) with the invention of bureaucracy—a system that’s since been adopted by countless states and has evolved into the contemporary field of civil service.

During the Eastern Zhou period, China was wracked by warfare, which created the need to collect taxes, organize a large military, and keep records. Bureaucracy began in the military and was later adopted by the civilian government. Bureaucrats were selected for their skills rather than their familial connections, and this shift ultimately let state leaders exercise much more power than when they had to navigate a government staffed by their relatives.

(Shortform note: Some scholars disagree with the notion that states had to break kinship bonds in order to exist, arguing instead that some states arose as a way to extend kinship bonds throughout a given territory. For example, one scholar argues that the early Chinese state was created by elites looking to help their kin who were dispersed across the far reaches of the empire. By building a strong central state, he argues, these elites hoped to extend protection and services to their kin throughout the realm.)

The other way states have escaped kinship ties is by avoiding them altogether. For example, Fukuyama argues that, in Western Europe, the Catholic Church dissolved extended kin relationships before states ever formed. He explains that, in order to expand its land and wealth, the Church systematically opposed practices (such as intermarriage between cousins and adoption) that tended to keep these resources bound up in hereditary kin groups. The result was that more Christians died without heirs and willed their property to the Church. A side effect was that European society abandoned the large, interrelated kin groups found in other societies.

(Shortform note: More recent research backs up Fukuyama’s assertion that the Catholic marriage policies paved the way for European state formation. One study finds that regions with high rates of cousin marriage tend to have fewer democratic institutions as well as lower levels of political participation, whereas areas that were influenced by the Church have participatory institutions dating back as far as medieval communes—autonomous cities that first arose in the 11th-12th centuries based on collective government by their citizens.)

Crucially, this move away from kinship happened before European state-building began, which meant that European states never had to reckon with kinship. Instead, Fukuyama says, European society became individualistic, meaning that decisions about issues like property and marriage fell to individuals rather than kinship groups. As a result, European society reorganized around impersonal, contractual property relations—relations that, as we’ll see, were important to the later development of accountability.

(Shortform note: Furthermore, the Catholic Church’s political infighting may have helped define the first European states. Some historians believe that nationalism first arose in Europe due to conflicts and schisms within the Church. For example, from 1378-1417, there were two popes, one in Rome and one in Avignon. This split papacy may have contributed to a sense of national allegiance organized around religious loyalties.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Francis Fukuyama's "The Origins of Political Order" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Origins of Political Order summary:

- What modern democracy is and where it came from

- The three components a stable democratic society requires

- Three important takeaways from Fukuyama's book