This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Shoe Dog" by Phil Knight. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

In 1980, Nike finally went public through their IPO, 18 years after Phil Knight got started in the shoe industry with Blue Ribbon Sports. Learn about the history of Nike’s IPO and their long refusal to go public.

1977

Sales reach $70 million. A trusted business adviser laughs at how precarious their float situation is, and he insists going public with a Nike IPO is mandatory to solve their cash flow problem. Otherwise, Phil might lose his company.

And then a bomb drops. US Customs wants $25 million for retroactive duties on shoes. This is based on an esoteric rule, the “American Selling Price.” In essence, the ASP required import duties on nylon shoes to be 20% of the manufacturing cost, unless there’s a similar shoe on the marketplace – then it’s 20% of the selling price of the competitor’s shoe. A few American competitors like Converse and Keds declared their shoes similar and lobbied hard for this duty. They want to stifle Nike.

1980

This is the final year detailed in Shoe Dog, the year when Nike finally goes public through their IPO, 18 years after Phil Knight got started in the shoe industry with Blue Ribbon Sports.

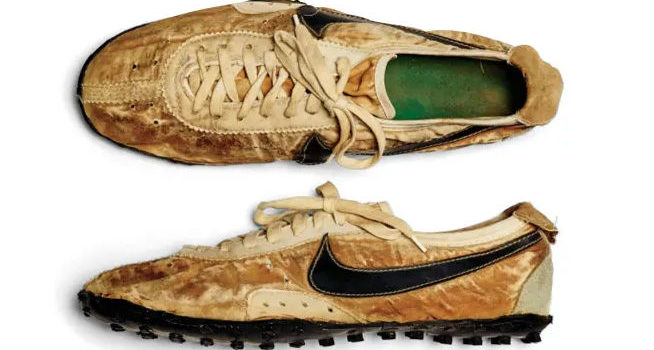

Tired of the plodding pace with US Customs and their fine, Nike goes on the offense. First, Nike launches its own low-cost nylon shoe, called the One Line. The import duties use a comparable shoe as the pricing benchmark, giving rise to the $25 million price. By using their own shoe as the comparable, they might reduce the claim.

Next, they produce a TV ad telling the story of the little Oregon company fighting the big bad government. Being forced to do this was un-American, it says.

Finally, Nike files a $25 million antitrust suit against their competitors and rubber companies, who had conspired to cripple them.

With so much heat, US Customs decide they wanted to move on. They initiate settlement talks, starting at $20 million, then $15 million. Phil doesn’t want to pay anything, even though they need to resolve this to go public, and they need to go public to survive. Eventually they settle on a final number – $9 million. Phil doesn’t like it, but he agrees. When writing the check, he muses that Nike has come a long way since he wrote his $1 million check in 1975 to pay Nissho – $1 million that he didn’t have.

Now they can go public, but Phil is still terrified of losing control of Nike through an IPO, that thousands of shareholders will ruin the Nike culture. Their solution is to issue two classes of stock – ordinary class B shares with one vote, and preferred class A shares for the current team that would let them name ¾ of the board.

Nike Goes Public

When they return from China, the Nike IPO process is in full swing. In September, they file to create 20 million shares of class A stock and 30 million of class B. 30 million shares would be held in reserve, and 2 million class B shares are sold to the public, somewhere between $18 and $22 per share. 56% of the class A shares would be held by the early team – Bowerman, their earliest investors, the Buttfaces, and Phil, who would personally own 46%. They agree that Nike needs to be run by one person, with one steady vision.

They go on their Nike IPO roadshow, convincing investors of the value of Nike. Phil tells stories to bankers about the company’s history, their dogged diligence, Bowerman’s experiments with his waffle iron. He wants the New York bankers to know that these Oregonians weren’t messing around.

This is a perfect time to be reflective and nostalgic. Phil remembers all the struggles they endured, not being able to pay Nissho, their paychecks bouncing, Johnson’s endless letters asking for encouragement. Phil’s mom remembers the first time she bought Phil’s Onitsuka shoes.

Phil wants no less than $22 per share. He believes they’re worth that much. A company called Apple is also going public that week, and he believes Nike is worth no less than they are. The bankers initially disagree, but Phil stands his ground, and they relent.

They finally go public with the Nike IPO. Instantly, the team is made. Bowerman is worth $9 million; Woodell, Johnson, Hayes and Strasser each about $6 million; Phil, $178 million.

Phil muses on becoming a businessman, a word he dislikes. To him, business isn’t about money or deals or fixing problems. It’s about the mission of contributing to other humans. It’s about making strangers happier or healthier, efficiently and intelligently.

He recalls all the sports matches he’s seen where a team had a big lead in the final quarter, relaxed, and lost the game. Even though he’s now wealthier than he had ever imagined, nothing had really changed. So he goes back to work.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Shoe Dog" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Shoe Dog summary :

- How Phil Knight started Nike when he was just 24 years old

- The lawsuit that almost ended Nike

- The ups and downs of Nike over 20 years of business

Thanks for sharing this information.