This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Gulag Archipelago" by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How does the cycle of abuse work in an institution? Is “just following orders” a valid defense?

In The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn doesn’t excuse the brutal actions of officers and guards. However, he argues that they were under incredible pressure from the state to participate in violence and believes that most acted out of fear of their leaders, the desire for safety, and the need to conform.

Read more to learn about corruption in the Soviet gulag system.

Just Following Orders in the Gulags

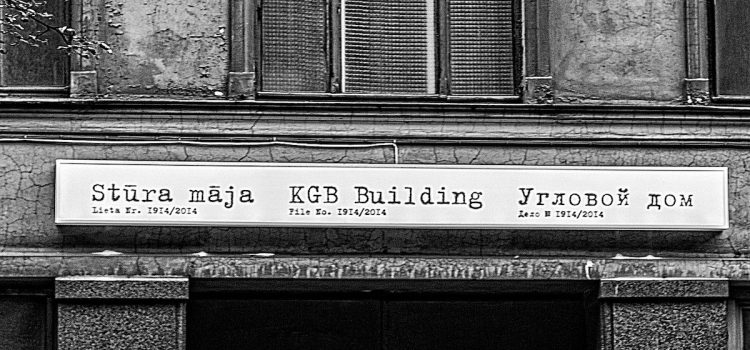

While much of The Gulag Archipelago focuses on detailing the abuse prisoners suffered at the hands of low-level state representatives—the police, State Security officers, and camp guards—Solzhenitsyn also stresses that these representatives were themselves victims of indoctrination and social alienation. He discusses how the police and security officers were conditioned to feed the cycle of abuse, participating in a “just following orders” culture.

Desensitizing Recruits

While it was obvious that joining State Security would require you to act against your neighbors, many were attracted to the job because it paid well and had ample opportunities for advancement. Soviet propaganda depicted State Security as the defenders of the people and the righteous arm of the state, rooting out evil. Many recruits came straight from communist youth organizations, state-run universities, and the military, and so had already bought into this framing to some extent.

Once they joined, it was easy for the power they wielded to go to their heads. Representatives of State Security and the police, no matter how young or inexperienced, were treated with deference by all members of society. This was partly due to the effectiveness of propaganda, but also to fear—everyone knew that these officials could arrest anyone they liked and were under pressure to constantly make new arrests just so they could be seen working. Some used their power to settle personal grudges, such as by having romantic rivals arrested.

These recruits were quickly exposed to the kinds of abuses they were expected to participate in. They would observe their superior officers beating, torturing, robbing, and sexually assaulting prisoners and were encouraged, if not outright ordered, to participate. Compliance showed loyalty, while refusal or squeamishness was mocked or punished. Showing too much sympathy for a prisoner could get you arrested for anti-Soviet sentiment.

| “Just Following Orders” as a Defense In the full version of The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn quotes from letters he received from a number of current and former security officers. Many were defensive about their participation in the abuse of prisoners and argued that they had no choice but to follow orders. The “just following orders” defense is a controversial one in human rights debates, due in large part to its association with the Holocaust and the Nuremberg Trials of 1945-46. The trials concluded that the “superior orders” defense was illegitimate in cases where the order being given would violate international law and that the requirements of military obedience don’t relieve you of the responsibility to make the right “moral choice.” While most modern states comply with the trials’ conclusion, modern attempts to hold soldiers accountable for war crimes or other violations of international law still tend to divide responsibility based on the defendant’s position of power and level of direct participation—a grunt soldier will likely be prosecuted less harshly than the commander of their unit. |

Solzhenitsyn gives some accounts of security officers who acted against orders to assist their victims—stopping a beating, warning a free civilian under suspicion to run, turning a blind eye to the theft of extra rations, and so on. However, these stories are far and few between, and Solzhenitsyn points out that the kind of official who would behave this way rarely rose within the ranks of State Security, lacking the cruelty and initiative that would impress their superiors and get them to the point of rewriting policy.

(Shortform note: Solzhenitsyn’s point is very similar to the “no good cops” argument made by modern anti-police and anti-prison activists, who assert that it’s impossible for there to be good individuals within an inherently exploitative system. Even if an individual acting alone could make a difference, those who resist abusing their power and try to help victims are often openly reviled by their peers and become victims themselves. Examples include the number of police officers killed or threatened for exposing corruption within their precinct and the widespread hatred for and undermining of Internal Affairs and similar accountability organizations.)

Solzhenitsyn’s Reflections

Solzhenitsyn himself nearly became a security officer, and while he ultimately refused on moral grounds, he admits that he behaved nearly as badly as the average camp guard once he was an officer in the Red Army. He was encouraged to mistreat the men under his command, and, even after his arrest, he failed to regard his fellow prisoners as equals. Only after years of imprisonment did he begin to regret his actions. He claims that he behaved so cruelly not because it was necessary or even because he enjoyed it but because it was expected of him.

| The Appeal of Abusing Others Numerous psychological studies have concluded that giving people unchecked authority and encouraging them to feel solidarity with one group and superiority over or distance from another can lead otherwise law-abiding and moral people to commit horrific acts of violence. Two infamous examples include the Stanford Prison Experiment and The Third Wave, both of which were shut down early after the detrimental effects on their participants became obvious. These experiments both found that it took only a few days for a group of seemingly normal students, having been given absolute authority over their peers, to begin enforcing authoritarian rules of conduct and treating anyone who resisted with cruelty and sadism. The heads of these experiments, psychologist Philip Zimbardo and high school history teacher Ron Jones, concluded that their subjects were so attracted to the feelings of power and group acceptance that they willingly sacrificed their morals. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Gulag Archipelago summary:

- A book that was banned for exposing human rights abuses to the world

- A work of historical nonfiction that describes life in Soviet prison labor camps

- How the Soviet government used violence, paranoia, and repression to control their citizens