This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Caste" by Isabel Wilkerson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How did the caste system in America come to be? What influence did slavery have on the forming of the American caste system?

The American caste system started back in the 1600s when Blacks were taken as slaves due to their non-Christianity. What started as a religious hierarchy quickly turned into a racial caste system.

Keep reading to learn all about the development of the American caste system.

The American Caste System

According to Isabel Wilkerson, the author of Caste, the caste system in America is divided into two primary castes: The dominant caste consists of people considered “white,” and the lowest caste consists of people considered “Black.” This system has its roots in the American institution of slavery, which was the standard mode of operation on American soil for 246 years, from 1619 to 1865.

(Shortform note: Wilkerson briefly mentions a “middle caste” composed of people who don’t fit into either the dominant or subordinate group, such as Native American and Asian American people. However, because racial tensions in the United States have historically revolved around the distinction between “white” and “Black,” she focuses the majority of her analysis on the upper and lower castes rather than the middle caste. While focusing specifically on anti-Black discrimination is valuable, ignoring anti-Native American discrimination seems like a significant oversight, since some scholars estimate that roughly 13 million Indigenous people in what is now the United States lost their lives to dominant caste violence, disease, and racism between 1492 and 1900.)

How the American Caste System Came to Be

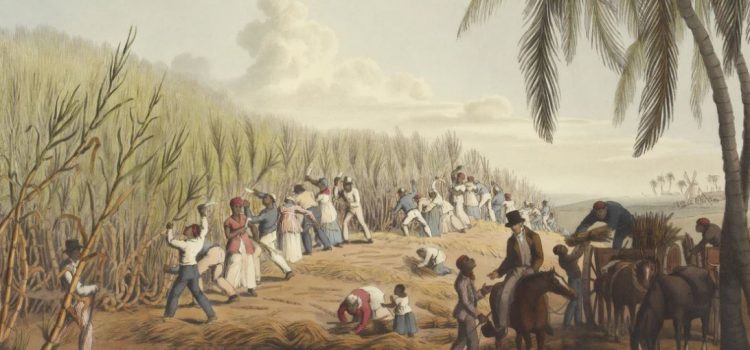

To understand why slavery played such a pivotal role in forming the American caste system, we need to understand how and why chattel slavery began in America. According to Wilkerson, the Europeans who claimed the land that was to become the United States of America in the 1600s saw an opportunity to build a prosperous existence—but to do so, they needed to turn the wilderness they found into civilization. The indigenous people were unwilling to give up their ancestral land, so the European settlers murdered or exiled them. Then, the Europeans searched for a group of people they could control to extract the untapped resources of this pristine landscape.

(Shortform note: Wilkerson’s story of how the European settlers overcame the indigenous people they met is arguably missing some crucial detail. A reason why the Europeans were so easily able to conquer the indigenous population is that even before they began their all-out assault on these peoples, they’d already indirectly weakened them. When Europeans began settling in the Americas, they brought over diseases like smallpox that the native population had never encountered, which launched a full-scale epidemic among Indigenous Americans. As a result, the native population had fewer resources to resist European encroachment on their land.)

Initially, European settlers chose to enslave African people—not because of their dark skin, but because of their religion. According to the author, for centuries, religion was the guiding distinction between who had power and who didn’t in Europe. At the top were Protestants, who used the Bible as evidence of their God-given superiority. British Christian missionaries conquered other undeveloped nations and exerted their power by colonizing the natives. Therefore, Wilkerson argues, the Europeans saw non-Christian African people as their inferiors and had no qualms about transporting them to the new world to build their kingdoms.

However, Wilkerson argues that once Africans started to convert to Christianity, the religious distinction vanished, and the Europeans needed a new way to justify their subordination. The obvious choice became the stark contrast in skin tone. Thus, they invented two classifications of people—those with light skin became one group called “white,” and those who were not white became “Black,” or the opposite of white.

| Enslavers Debated Converting Enslaved People to Christianity Wilkerson notes that religion was the original justification for slavery. However, she doesn’t explore the fact that as a result of this initial justification, slaveholders and other colonists in the 17th and 18th centuries were divided on whether converting enslaved Africans to Christianity was wise. According to Ibram X. Kendi in Stamped From the Beginning, the idea of enslaving fellow Christians created a moral quandary for enslavers—if enslaved people converted to Christianity, it would elevate them closer to equal caste status with enslavers, who would then feel guilty for inflicting torturous treatment on them. The laws of the time reflected this tension: In the British-ruled American colonies, it was technically illegal to enslave a Christian, and at least one formerly enslaved woman had successfully sued for her freedom on those grounds. However, despite the drawbacks for enslavers, some prominent colonial figures promoted religious conversion as a tool of subjugation. They felt that if they converted enough enslaved Africans, they could convince them that being a dutiful slave was the surest path to salvation, which would reduce the likelihood of them ever challenging the established social order. In their eyes, a Christian slave was a more docile slave. The laws in the colonies soon evolved to allow for the existence of Christian slaves. |

The American Institution of Slavery

Wilkerson describes how, in the eyes of enslavers, slaves weren’t people—they were symbols of commerce. Their sole purpose for existing was to serve as the machine that generated profits for the landowners. Slaves could be traded like cattle, auctioned like farm machinery, or given away as gifts. They had no say in who they worked for or where they were sent, and they could be separated from loved ones without question. One owner might brand his slaves to stake a claim to them, and owners often sold children to cover debts or settle disputes.

(Shortform note: The fact that enslavers thought of enslaved Africans as property, not people, somewhat undercuts Wilkerson’s argument that American society during slavery was universally understood as a caste system. Enslavers may not have thought of enslaved Africans as a lower caste because caste systems only apply to people, not to property. Therefore, while outside observers and enslaved people might have viewed this society as a caste system, enslavers may have disagreed.)

The institution of slavery made slave owners wealthy beyond imagination. (Shortform note: Some scholars estimate that the richest enslavers would have been billionaires in today’s dollars.) According to the author, this benefit helped the dominant caste validate and normalize the forced labor and torture of the lowest caste. Furthermore, the dominant caste grew accustomed to punishing the subordinate caste for any behavior that threatened their power, and they had the full force of the law on their side. This mode of life cemented the ideologies of the dominant caste into an American culture that perpetuated well after slavery ended.

The violence involved in this domination, including whippings, sexual assault, and starvation, is too horrible for many modern Americans to acknowledge or examine. Wilkerson argues that acknowledging this vicious behavior goes against the ideals of freedom, opportunity, and democracy that are at the heart of American society, historically and today. But intentional ignorance allows the cycle of violence to perpetuate. (Shortform note: This reluctance to acknowledge the horrors in America’s history has contributed to widespread debates over whether teachers should include information about systemic racism in their curricula. Opponents think that dwelling on systemic racism will actually perpetuate racism rather than help to eliminate it because they believe that discussing institutional racism paints white people as fundamentally bad and Black people as “helpless victims.”)

| Wilkerson Undervalues the Impact of Capitalism on Caste Hierarchies While Wilkerson acknowledges that slavery was an economic institution, some reviewers argue that she doesn’t fully analyze the role of economic self-interest in creating and maintaining racial inequality. For example, one Boston Review writer points out that the word “capitalism” doesn’t appear even once in Caste’s nearly 500 pages. The same reviewer argues that this is a major omission on Wilkerson’s part because it is impossible to fully analyze the racial hierarchy of the United States without analyzing the economic structure that created that hierarchy in the first place. Wilkerson’s omission of any discussion of capitalism is particularly glaring because, as Yuval Noah Harari argues in Sapiens, American slavery reveals a major flaw in capitalism as an economic structure: It provides no natural check against human greed and cruelty. According to Harari, the theory of capitalism relies on the assumption that employers will reinvest their profits in the workforce by creating more jobs. However, enslavers sidestepped that responsibility and chose instead to eliminate payment for their workers altogether, resorting instead to motivating them with unspeakable violence rather than fair pay. The nature of the capitalist system enabled this violence by allowing the cruelest enslavers to reap the most profit. |

The Legacy of Slavery

Wilkerson describes how after Reconstruction (a 12-year period of federally enforced racial equality following the end of the Civil War), dominant caste people in the American South swiftly reclaimed the power they’d been forced to give up. Once federal troops withdrew from the South, the dominant caste created laws that instigated a new type of oppression of the subordinate caste. The laws dictated where Blacks could live, what types of jobs they could hold, and how they could be educated.

(Shortform note: These laws are known as Jim Crow laws (“Jim Crow” was originally a popular minstrel show character portrayed by an actor in blackface). In addition to the formal laws that Wilkerson mentions, the Jim Crow era also featured a number of social codes that dictated behavior. For example, Black people could not show physical affection to one another in public or sit in the front seat of a white person’s car.)

At this time, more European immigrants began to arrive at Ellis Island, and a new indoctrination into American society took shape. According to the author, the caste hierarchy based on skin color was the leading principle of the nation, and if immigrants wanted to make it in America, they had to get on board. People who had no experience with or prejudice against Blacks before now joined a system of hatred to survive and thrive. Wilkerson believes this scenario efficiently kept those of African heritage at the bottom despite their freedom from slavery.

(Shortform note: In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari argues that this exchange is at the heart of immigration in all countries, not just the United States. Immigrants assimilate and adopt the normative attitudes of their host country; in exchange, they’re welcomed into the fabric of their host country’s society.)

Generation after generation grew up within this distorted system, and the author argues that today, the continued suppression of the subordinated caste is normal. Their continued debasement helps justify their status as lesser humans, and those in the middle caste still understand that to curry favor with the dominant group, they must dehumanize the lowest.

(Shortform note: While Wilkerson describes how members of the middle caste have embraced this phenomenon out of necessity, other authors have pointed out how the dominant caste strategically encouraged this pattern. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander describes how, throughout history, powerful members of the dominant caste have protected their power by encouraging middle caste and less-powerful dominant caste people to dehumanize the lowest caste. For example, wealthy planters in the American colonies gave poor white planters scraps of power over enslaved people, such as allowing them to lead slave patrols. That way, they could minimize the threat of poor white people and enslaved Africans joining together to overthrow the wealthy plantation owners.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Caste summary :

- How a racial caste system exists in America today

- How caste systems around the world are detrimental to everyone

- How the infrastructure of the racial hierarchy can be traced back hundreds of years