Why did American colonial elites fear slaves? What role did slaves play in the Revolutionary War and Civil War?

In A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn includes a history of slaves in America. He explores their experience during colonial times, the Revolutionary War, and the Civil War. He also takes a look at freed slaves during the Reconstruction era.

Keep reading to learn about life for these so-called “persons of mean and vile condition.”

Why Slaves Were Considered “Persons of Mean and Vile Condition”

Zinn’s history of slaves in America is put into the context of society as a whole. Through the 17th and 18th centuries, British elites established a number of colonies in North America. These colonies functioned according to a hierarchical class system with wealthy white men on top:

- Financiers, aristocrats, and merchants in Britain invested in—and extracted as much resource wealth as possible from—the colonies.

- Elites in the colonies themselves managed the harvest and sale of resources, owning a majority of colonial farmland and manufacturing facilities.

- A middle class of skilled laborers and small landholders made less than elites, but enough to live independently.

- Poor white laborers and farmers worked directly for American elites, while American Indians and slaves (“persons of mean and vile condition”) had few or no rights or property.

(Shortform note: The colonial class system Zinn discusses is the model of settler colonialism, where a colonial power—in this case, primarily Great Britain—encourages a large number of its own people to move to colonies and replace the Indigenous population. To accomplish this, the colonial power invests in the growth and development of their colonies. Settler colonialism contrasts with extractive colonialism like the kind practiced by Spain (and by extension, Christopher Columbus), where a colonial power sends only a small number of men to extract as much resource wealth as possible by killing and enslaving Indigenous people.)

Zinn discusses the experience of slaves within this system’s lower class and how they tried to improve their circumstances.

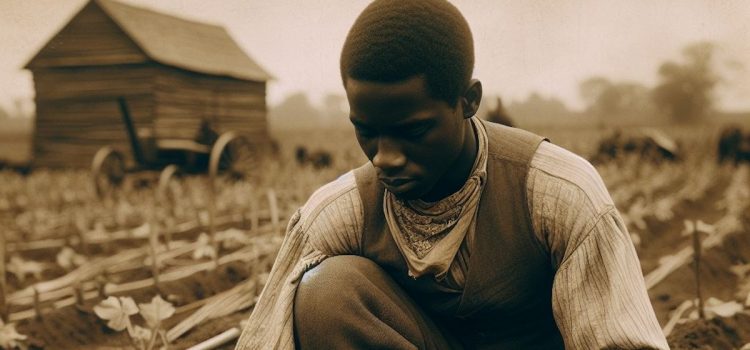

Enslaved Africans (and, in future generations, African-Americans) provided a large force of free labor that was crucial for the early survival and profitability of the American colonies, explains Zinn. He argues that, while ideas of white racial superiority and racism existed before the slave trade, they became widespread and dominant because of it.

Slavery existed in Africa before Europeans arrived, but on a smaller scale and under less brutal conditions. Under capitalism, though, slavery became a massive and horrific industry. Slaves were kidnapped (usually in West Africa), separated from their cultures and communities, and then shipped in horrible conditions to be exploited for the rest of their lives. They had no rights and no property; white colonists often tortured, raped, and killed them with no repercussions.

(Shortform note: In The 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones further details how the survival and prosperity of the colonies relied almost exclusively on enslaved people. She explains that in the early days of colonies like Jamestown, enslaved Africans performed a lot of the manual labor crucial for survival like building homes and clearing land to grow crops. In addition, they imparted crucial agricultural knowledge and disease prevention strategies to improve colonial crop yields and survival rates.)

Elites promoted white supremacy and racism to justify the slave trade and to sow division between poor whites and Black slaves—they feared that these two groups working together could overthrow the colonial class system. This nearly happened in 1676, Zinn notes, when English colonist Nathaniel Bacon united poor whites and Black slaves to revolt against the colonial government. After quelling the rebellion, colonial elites passed a number of “slave codes” formalizing race-based segregation to prevent a similar event from happening again. Without the option of revolt, some enslaved people resisted oppression through working slowly, sabotaging the workplace, suicide, murdering slave owners, or running away.

(Shortform note: Some historians argue that, in addition to white supremacy, “whiteness” and the “white race” as concepts were invented during the colonial era. They note that these phrases as we understand them today first appear in writing around the 17th century, and primarily serve to distinguish European colonizers and slave owners from enslaved Africans and exploited Indigenous peoples. Because of political and economic conditions of the era, skin color became a shorthand for social class—a shorthand elites emphasized to keep lower classes divided.)

Slaves During the American Revolution (1765-1783)

During the American Revolution, American elites recruited poor whites to fight the British instead of resisting the colonial class system. Slaves mainly fought for Britain, who promised freedom in exchange for service. Indians also mostly fought for the British, as they had halted westward expansion.

(Shortform note: Some historians argue that the American Revolution was also fought to preserve slavery in colonial America. These historians note that in the late 18th century, enslaved Africans throughout the Caribbean were participating in more and more organized and disorganized revolts. This growing unrest made the British consider abolishing slavery—they were concerned that a slave revolt combined with an enemy invasion could lose them their colonial possessions. Colonial elites responded with the American Revolution, fighting to ensure they could continue owning slaves. This theory also helps explain why so many enslaved people fought for the British during the Revolution in exchange for their freedom.)

Slaves During the Civil War (1861-1865)

Zinn argues the American Civil War was caused by conflicting economic interests of Northern and Southern elites. The Northern elite of bankers, merchants, and industrialists wanted an industrial economy, while Southern plantation owners wanted an economy based primarily around agriculture and slave labor.

For decades, this conflict played out in political debates over the expansion of slavery to new states—expanding slavery would mean more pro-slavery congressmen and a larger portion of the economy dedicated to slave agriculture. Northern elites made countless concessions to Southern elites during this era, prioritizing stability over ending slavery. But this conflict ultimately couldn’t be resolved through politics alone. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president on the platform of stopping the expansion of slavery, Southern elites decided to secede from the country and formed the new Confederate States of America. The North, also known as the Union, then went to war to defeat the rebellion and reunify the country.

Though conflict among the elites caused the Civil War, Zinn explains that the poor fought and paid for it. Hundreds of thousands of poor Americans fought and died on both sides of the conflict as it became much longer and larger than expected. The wealthy, on the other hand, could pay to avoid the draft or hire a substitute to fight for them. Free Blacks and slaves were a decisive factor in the war, Zinn suggests—as many as 200,000 free Blacks and escaped slaves joined the Union army, while slaves within the Confederacy crippled its economy by running away, refusing to work, or turning on their owners.

Freed Slaves During Reconstruction

Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, there were many questions about what would happen to ex-Confederate leaders, how the government would redistribute land and wealth seized in the South, and the fate of the newly freed slaves. The process of answering these questions was known as Reconstruction. Zinn argues that questions of wealth and racial equality were linked—without the redistribution of land and wealth, legal rights and citizenship would be insufficient to grant Black Americans equality.

For a time, things seemed hopeful—Northern Republicans had a vested interest in developing Southern Black communities to grant them a new voter base. Under the protection of the Union army, Black political communities formed in the South, electing officials to local, state, and even federal positions. The government established mixed-race public education as well as laws and amendments protecting the rights of Black Americans.

However, the government ultimately returned most of the land and wealth it seized to white ex-Confederates. Some freed slaves pooled their money to buy land, but a majority had little to no property and had to work for former slave owners under harsh conditions for minimal wages. Southern whites organized the Ku Klux Klan and other groups dedicated to terrorizing and destroying Black communities. Eventually, Northern support for Black reconstruction waned in favor of a return to the status quo, and Southern whites were able to effectively ignore the new laws protecting Black rights.

| The Lost Cause of the Confederacy After regaining their wealth and influence, many ex-Confederates used it to try to rehabilitate their public images. They created the historical narrative of a “Lost Cause of the Confederacy,” arguing the Confederates fought for a cause nobler than preserving slavery. Ex-Confederates cited loyalty, states’ rights, and protecting a distinct Southern culture as reasons why they fought in the Civil War. In addition, the Lost Cause depicted Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee as noble and heroic men. Many of the main ideas of the Lost Cause persist to this day in America, though they’ve started to face increased scrutiny in the past decade or so. |