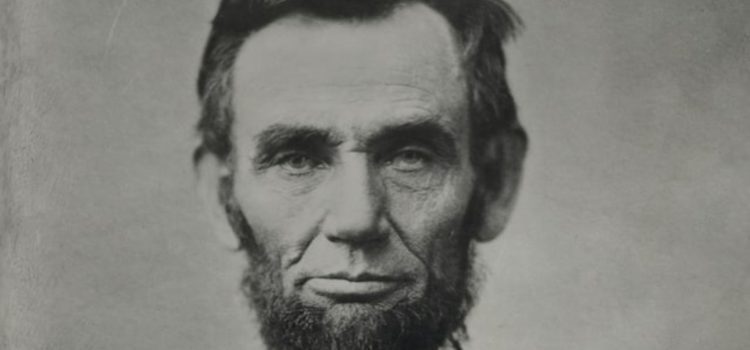

How and why did Abraham Lincoln get into politics? When did his centrist approach fail him? What song did he want played after the announcement of the Union’s victory?

In And There Was Light, historian and biographer Jon Meacham discusses Abraham Lincoln’s political career, including the president’s actions during the Civil War. Meacham also provides some background information that sheds light on Lincoln’s politics and abilities.

Continue reading to learn about Abraham Lincoln’s political career.

Abraham Lincoln’s Political Career

Before diving into the details of Abraham Lincoln’s political career, let’s look at a couple of points from Lincoln’s childhood that tell us something about his convictions and talents that were on full display later in his life. Meacham writes that, even as a child, Lincoln had a reputation as a politician and mediator. He was often called on to settle disputes between boys his own age, and they usually respected his decisions.

Lincoln was raised as a Baptist. He believed that God called upon all humans to be fair, merciful, and loving to one another. That conviction would guide many of Lincoln’s actions, both in politics and in his private life. In addition to shaping his morality, Lincoln’s religious upbringing influenced his political views: Many Baptists opposed slavery, and abolition was a common topic in conversations and sermons.

Lincoln’s Early Political Career: 1830-1849

In March of 1830, the Lincolns moved to Illinois (a Northern state). Shortly after that, Abraham Lincoln moved by himself to New Salem, Illinois; Meacham says that’s when Lincoln left behind his farming life and got involved in local politics.

Inspired by the highly political atmosphere of the time, Lincoln gave his first public speech in the early summer of 1830. He spoke about the need to clear trees and other obstacles from the nearby Sangamon River. Meacham says the speech went well: Lincoln had natural charisma; his points were well-reasoned and persuasive; and perhaps most importantly of all, he found that he enjoyed being the center of attention.

(Shortform note: Firsthand accounts of Lincoln’s speeches largely agree with Meacham. Even during his first attempt at public speaking, he was a remarkable orator and debater (although his mannerisms were rather awkward). Journals and newspapers also regularly praised Lincoln for his clear, well-reasoned arguments and the forceful way he delivered them.)

Lincoln not only shared his viewpoints orally but also in writing—some of which stirred up controversy. Meacham says that—despite his Baptist upbringing—Lincoln at times openly questioned his faith. For instance, in the early 1830s, he wrote an essay exploring the contradictions within Christianity’s teachings. That essay was widely read and talked about until a friend of Lincoln’s took the manuscript and destroyed it, saying it was unwise for someone with Lincoln’s political ambitions to be associated with such unpopular and radical ideas.

(Shortform note: The exact contents of Lincoln’s essay about Christianity—or whether such an essay even existed—is an issue of some debate among historians. Some Lincoln scholars point out that there are no firsthand accounts of anyone reading that essay or listening to someone else read it. An alternate theory is that Lincoln wrote an essay defending his personal view of Christianity, but not attacking the religion itself. However, there is firsthand evidence of people using Lincoln’s supposed lack of devotion to hurt his reputation: For instance, in 1846, one of Lincoln’s political opponents spread rumors that Lincoln openly scorned Christianity and the Bible’s teachings. Lincoln wrote a letter specifically to refute that rumor.)

Meacham adds that Lincoln began his political career in earnest as a state legislator. He served four terms in the Illinois legislature from 1834 to 1842.

(Shortform note: As an Illinois legislator, Lincoln was notable for his idealism and his drive to boost the state’s economy. He spearheaded many public works projects, most notably in transportation—for example, he championed efforts to clean and expand the state’s waterways and to build new railroads. However, Lincoln’s idealism and determination weren’t yet tempered by the caution he would learn later in his political career; the expensive projects he fought for, coupled with a major economic downturn (the Panic of 1837), created serious hardship and massive debt for a lot of Illinois residents.)

Lincoln Begins Confronting Slavery

Meacham says that slavery versus emancipation was one of the biggest, if not the biggest moral and political question of Lincoln’s lifetime. Lincoln was a member of the Whig Party, which opposed slavery but believed that the federal government didn’t have the power to abolish it. Therefore, Lincoln favored a gradual cultural shift instead of a federal mandate to free enslaved people: He and his colleagues hoped that, as more and more states voted to emancipate their enslaved residents, the states that still favored slavery would feel increased political pressure to abolish it as well. In this way, all enslaved people could eventually be freed without the risk of the federal government overstepping its Constitutional powers.

Lincoln also served a single term in the US House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. In 1849, in his role as a representative of Illinois, Lincoln proposed a resolution that would eliminate slavery in just Washington, D.C. He put forward a moderate plan, which he hoped would free enslaved people without upsetting enslavers too much—for example, the resolution required enslavers to be compensated for the full value of any enslaved people they freed.

However, Lincoln’s plan was almost universally rejected. Abolitionists thought he was being too generous to enslavers, while slavery advocates were against any proposal to abolish it. For the first time, Lincoln’s centrist approach to politics failed him.

Lincoln Runs for President: 1856-1861

Meacham explains that Lincoln joined the newly formed Republican Party in 1856. He ran for an Illinois Senate seat in 1858, but he lost narrowly to Democratic Party candidate Stephen Douglas.

Despite his loss, the political world took note of Lincoln’s debate skills; he quickly became popular among his colleagues not just in Illinois but across the entire country. As a result of his newfound fame, the Republicans chose Lincoln as their presidential candidate in 1860, and he won the election.

In 1861, at the age of 52, Abraham Lincoln took office as the 16th president of the United States.

Backlash to Lincoln’s Win: 1860-1861

Lincoln, as well as the Republican Party as a whole, strongly opposed slavery. Therefore, Lincoln’s win pleased abolitionists, but he and his colleagues feared retribution from slavery advocates. In fact, Meacham notes, there were rumors that former Virginia Governor Henry Wise was raising an army of 25,000 men, with a plan to march on Washington, D.C., and stop Lincoln from taking office. The rumors of an attack on Washington, D.C. proved false; instead, the pro-slavery South decided to leave the Union entirely.

Lincoln’s Leadership During the Civil War: 1861-1865

Meacham tells us that, after the Southern states announced they were breaking away from the Union, President Lincoln made an uncharacteristically one-sided statement: He wouldn’t compromise with the Confederacy, and he wouldn’t allow the nation to split. In other words, Lincoln didn’t recognize the states’ right to secede; he was determined to dissolve the Confederacy and bring its members back into the Union.

The Confederacy responded by making the opening move of the American Civil War. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces attacked a federal garrison in South Carolina called Fort Sumter. The following morning, Lincoln made another statement saying that he was prepared to meet violence with violence, and so the war began in earnest.

Meacham says that, during the Civil War, Lincoln wondered whether God would favor the Union or the Confederacy. In other words, Lincoln came to view the war as a religious and moral struggle, not just a military one; he believed God would ensure victory for whichever side was morally right.

The Emancipation Proclamation: 1863

On January 1, 1863, two years into the Civil War, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law. By doing so, he officially freed all enslaved people in Confederate states—though, as Meacham points out, not those in the few Union states where slavery was still legal.

Meacham adds that Lincoln’s decision to finally sign the Proclamation wasn’t driven only by morality. The Union was struggling in the Civil War, and Lincoln hoped that emancipation would encourage more Black Americans in the North to join the fighting, thereby bolstering the Union’s ranks. His gambit worked, and as a result, the Union gained a decisive edge.

The Gettysburg Address: 1863

On November 19, 1863, slightly less than a year after signing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln delivered a short speech called the Gettysburg Address. This speech was part of a ceremony to consecrate the Soldiers’ Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The Address condensed decades’ worth of Lincoln’s thoughts into a few minutes of speaking. In it, he made a case for freedom, equality, and democracy for all US citizens—regardless of skin color or ethnicity—and renewed his promise that the United States would be a place of liberty and opportunity for everyone.

The War Ends: 1865

Meacham tells us that Lee had set up a base in the town of Appomattox, Virginia, from which he was defending the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. However, on April 2, 1865, Lee sent a telegraph to Confederate President Jefferson Davis saying that he could no longer hold his position. Richmond fell to Union forces that same day.

On April 9, 1865, Lee signed the Articles of Surrender at the Appomattox Courthouse. The Articles affirmed that the Confederates surrendered completely and unconditionally to the Union.

The next day, at dawn, a barrage of cannons fired in Washington, D.C., to announce the Union’s victory. Lincoln gave a brief speech, then asked some nearby musicians to play “Dixie,” a popular song that the Confederacy had taken as its national anthem. Meacham says that, by requesting that specific song, Lincoln was signaling his desire for Reconstruction—in other words, his wish to reintegrate the rebel states into the Union and move forward as a united country.

Lincoln’s Assassination: 1865

Lincoln had won the Civil War, but he didn’t live long thereafter. Meacham explains that on April 14, 1865, actor John Wilkes Booth attacked Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Shouting “sic semper tyrannis” (“thus always to tyrants”), Booth shot the president in the head from close range. Lincoln died from the gunshot wound the following morning.