This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Hidden Figures" by Margot Lee Shetterly. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Who were the women of Hidden Figures? Were the Hidden Figures real women?

Yes, they were real! The Hidden Figures main characters, Dorothy Vaughan, Katherine Johnson, and Mary Jackson, were all real women who contributed to both the war effort and later to NACA (NASA) in the journey to space. Read more about the women of Hidden Figures, and how they overcame obstacles to make important discoveries in science and space travel.

Opportunities at NACA (NASA) and the Women of Hidden Figures

Hidden Figures: The Story of the African-American Women Who Helped Win the Space Race tells the story of a group of African-American women who, over a period of over 25 years, made major contributions to the US space program during its golden age. Overcoming racist and sexist discrimination, these women established themselves as brilliant mathematicians and engineers and helped lead the United States to victory in some of the pivotal moments of the Cold War-era space race—including John Glenn’s 1962 orbit of the Earth and the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing.

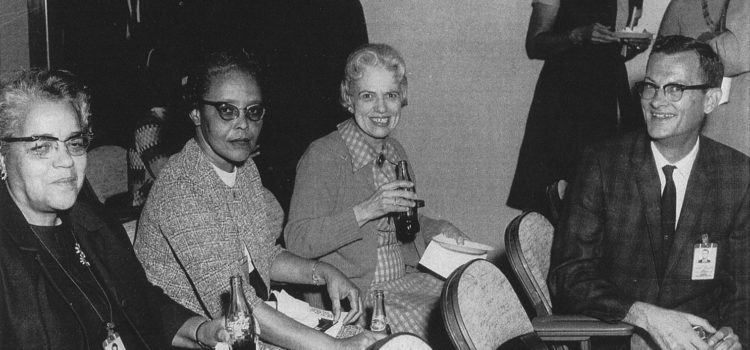

The women of Hidden Figures Starting in World War II, with much of the male workforce away, there were new opportunities available for women. Many of these women performed jobs that were essential to the war effort, and stayed on after the war to work in a new industry devoted to space travel. Three of these women, Dorothy Vaughan, Katherine Johnson, and Mary Jackson, are the focus of Hidden Figures. The Hidden Figures real people were scientists, activists, and pioneers of their industry and of equality.

Dorothy Vaughan

Dorothy Vaughan was one of the women of Hidden Figures who was first in the door at NACA, and later welcomes the others. One of the first to seize this new opportunity was Dorothy Vaughan. As a college graduate and high school teacher, she had reached the pinnacle of what was thought possible for black women at that time. Still, the inequality was inescapable—Virginia’s black teachers earned less than 50 percent of what their white counterparts did and worked in segregated, poorly funded, and dilapidated school buildings. But she was a passionate believer in education, believing that it was the best chance black children had to succeed in a country that forced them to work twice as hard to get half as far as white people. She poured herself into her work and was a passionate advocate for her students, even under the trying circumstances of Virginia’s segregated public schools. She even once sent a letter to a math textbook publisher when she discovered an error in one of their books, demanding that they correct it.

She had received her degree in education from Howard University, one of the nation’s premier black colleges. Because the white schools (including the Ivy League) refused to tenure black professors regardless of their brilliance, black schools like Howard had an over-abundance of extraordinary scholars. Dorothy had the opportunity to study under some of the nation’s greatest minds. Although she studied education in order to become a teacher (considered at the time to be the most stable possible career for a black woman) she had always had a passion for mathematics. Many of the Hidden Figures real people had a background in mathematics.

In 1943, Dorothy saw a job bulletin for a federal agency that was hiring women to fill mathematics-related jobs: NACA. Although the intended audience for this advertisement was likely the white students from the State Teachers College, it captivated Dorothy. This was also happening at a time when the black press was spreading the word that the federal government had cracked open the door of opportunity to African-Americans to work in the bustling war economy.

In 1943, typical black jobs might have been in domestic work (for women) or low-skill, low-wage agricultural industrial work (for men). A good black job would have been as a small business entrepreneur or as a unionized porter on a railcar. A very good black job would have been working as a teacher, minister, doctor, or lawyer. But the opportunity for a black person to work in an aeronautical laboratory (and not as a janitor or cafeteria worker) was something altogether new and extraordinary.

That spring, Dorothy filled out her application. In the fall, she received her answer: she was hired to work as a Grade P-1 Mathematician at Langley for the duration of the war. Her pay would be more than twice what she was earning as a high school teacher. Although the job would take her away from her husband, her children, and the community that she loved (they would only be able to see her during school breaks and scheduled visits), she knew she could not let this opportunity pass her by.

Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson is one of the best-known women of Hidden Figures. As chance would have it, Dorothy had had some contact with another future NACA pioneer: a black West Virginian named Katherine Coleman (she would become more famous under the name Katherine Johnson after she married her second husband). Dorothy’s husband, Howard, was a bellhop who worked seasonally at the famed Greenbrier hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. In the summer of 1942, a year before she took the NACA job, Dorothy and her family temporarily relocated to West Virginia, so Howard could be closer to his summer job. While there, the Vaughan family formed a close bond with the Coleman family, especially their brilliant 24-year-old daughter, Katherine.

Katherine shared Dorothy’s passion for mathematics and displayed signs of being a numerical prodigy as early as grade school. She poured herself into her studies at West Virginia State Institute, a black college near the state capital (which she entered after graduating high school at the age of 14), where she enjoyed a full scholarship. During her junior year, she was mentored by a young math professor, the brilliant William Waldron Schiefflin Claytor, who, recognizing Katherine’s talents, created special courses exclusively for her and prepared her for a career as a research mathematician. She matriculated to Howard University, where she graduated summa cum laude with a double major in mathematics and French.

In 1936, the NAACP scored some major legal victories before the Supreme Court, which ruled that explicitly barring black students from graduate programs was unconstitutional. States either needed to create “separate, but equal” programs for black students or allow them to integrate into the white schools. While some states (like Virginia, which actually subsidized black graduate students to study outside the state rather than allowing them to integrate) openly defied the court order, West Virginia opted to comply.

Katherine was one of the first three black students to enroll in the graduate program at West Virginia University in the summer of 1940, though she left early when she got married and had her first daughter. But that was hardly the only barrier she would break through. She and other Hidden Figures real people worked tirelessly on their own careers, and to forge a path for others.

Mary Jackson

The last to join the group of women of Hidden Figures was Mary Jackson. In 1951, a new 26-year-old hire named Mary Jackson made her way to West Computing. Whereas so many of her predecessors had been “come-heres,” transplants from other parts of the country, Mary was a “been-here:” she’d grown up in Hampton Roads and had deep roots in that part of Virginia. She graduated from high school in 1938, after which she had enrolled at Hampton Institute, an all-black college founded on the idea of self-help and practical and industrial training.

With these founding principles, most Hidden Figures real women at Hampton studied home economics, but Mary was different. She completed a double major in mathematics and physical science. After graduating, she married and started a family. Mary also became deeply involved in her local Girl Scout troop, where she committed herself to helping young African-American women make the most of themselves—with a special focus on helping them prepare for college careers. Some of the girls Mary helped benefited from learning from the women of Hidden Figures and later also worked at NACA (NASA).

Although the troop was segregated from the local all-white Girl Scout troop, Mary always took pains to show her girls that they deserved far better than what a racist society was prepared to give them. On one occasion, she stopped the troop from singing the slave spiritual “Pick a Bale of Cotton,” believing that performing it would only contribute to negative stereotypes of black people. She couldn’t remove the limits that Jim Crow placed on these girls, but she could remove the limits the girls placed on themselves.

Mary was working as a clerk typist at Fort Monroe in 1951. Her mathematical abilities quickly became obvious to her superiors, and with the Korean War heating up, there was an urgent need for more skilled computers at NACA. After just three months at Fort Monroe, the federal government transferred Mary to Langley, where she began working for Dorothy Vaughan. Like many other Hidden Figures real women, Dorothy’s supervision helped Mary rise through the ranks at NASA.

The women of Hidden Figures undoubtedly were a part of their country’s achievements. Not only did they perform jobs that would help change the world, but they overcame tremendous obstacles to do so. The Hidden Figures main characters, Katherine, Dorothy, and Mary, are real people whose contributions and achievements laid the groundwork for generations of women to come.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Margot Lee Shetterly's "Hidden Figures" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Hidden Figures summary :

- How brave black women were instrumental to the American space race

- How they confronted racism and sexism to forge a better future

- Their enduring legacy in American history