This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Art of War" by Sun Tzu. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What was the Warring States Period? What can it teach us about battle tactics?

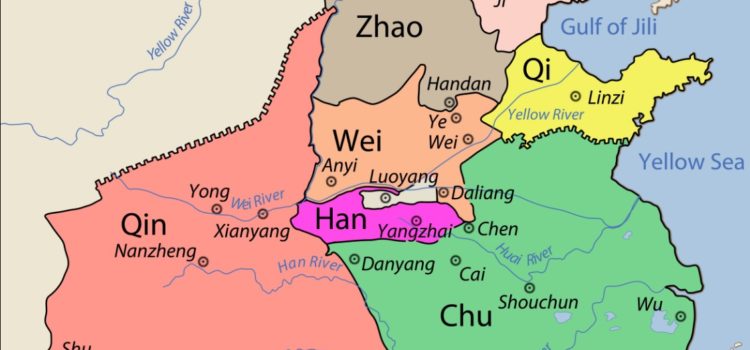

The Warring States Period, or Era of Warring States, was a period between around 480 B.C.E. to around 246 B.C.E. During this era, various Chinese dynasties were at war, including the Wei, Zhou, Han, and Qi. The Qi eventually won control of the area.

We’ll cover how the warring states formed alliances during this period and what we can learn from their turmoil.

Alliance in the Warring States Period

The Warring States Period (480 to 246 B.C.E.), or Era of Warring States, saw lengthy civil wars among the various kingdoms and is the era in which The Art of War was written. During this time, the states of Wei, Zhou, Han, and Qi were all viable. The Wei and Zhou joined forces against the Han, who sought assistance from the Qi in defense. The Qi, despite being a much smaller state, set out toward the Wei kingdom with the intent to attack.

The Wei general, upon hearing this news, left his station in Han territory and headed home. He was arrogant about the weakness and cowardice of the smaller Qi army.

The Qi commander sought the advice of Sun Tzu, who told him to have his army set a thousand fires the first night. On the next evening, the army was to set half the amount and repeat the process of the following night.

Hearing of the dwindling fires, the Wei general felt assured of victory and pompously took an elite force to wipe out the Qi. Concurrently, the Qi general estimated the timing of the Wei’s movements. He found a narrow section of road by which the Wei would be traveling at night and created a barrier across it: a large tree trunk with words carved into the side. He then surrounded the area with archers. When the Wei general approached the log, he lit a torch to read the engraving. The archers, now with an illuminated target, sent multitudes of arrows into the enemy. Seeing that his men were losing and that he’d fallen into a trap, the Wei general took his own life.

Lessons From the Warring States Period

In The Art of War, Sun Tzu describes two conditions of opponents in conflict: empty and full. Fullness signifies an army who is strategic and prepared and has the advantage. Emptiness signifies an army who is reactive and unprepared and is at a disadvantage. The Qi were the fullest army during the Warring States Period.

- You must avoid battle with people who are full.

- You must never battle when you are empty.

- The only mode of success is to strike the empty with the full.

Part of being full means always having the advantage. Staking claim to a battlefield first and waiting for opponents to arrive creates a position of comfort. Arriving last and encountering comfortable opponents creates a position of stress.

- If you are first, you are able to prepare. When you are prepared, you are assured and calm and have the advantage.

If you are last, the enemy has the advantage. When the enemy has the advantage, do not approach them. Retreat and go to new ground. During the Warring States Period, the Wei didn’t follow this advice.

Opponents will follow any path they believe leads to advantage and gain. Opponents will not follow any path they believe leads to harm. Therefore, the act of retreating will give your enemy the impression that you are not able to fight. They may see your retreat as an opportunity for gain, and you may be able to draw your opponent out. You will now be in the position of comfort and advantage on the new ground.

Whoever waits for the fight is full; whoever chases the fight is empty. If you retreat rather than engage when the opponent has the advantage, you will maintain your fullness. By forcing the enemy to come to you, you ensure their emptiness. This was the path of the Qi during the Warring States Period.

Do not follow the path your opponent sets for you. This was the Wei’s downfall. If they have a stronghold in one place, attack a different location to either divide or remove their power.

- If they go right, go left.

- Give your enemy the prospect of gain in front of them, then attack them from behind.

Six Tactics to Gain Advantage

1) Draw your opponents out. By continuing to draw your opponent out, you cause them to give up their advantage. You force your opponent to focus their strength in a particular direction. This was a strategy of the Qi during the Warring States Period.

- If they are comfortable, make them mobilize.

- Leaving a place of comfort creates stress.

- Forcing them to continually be on the defensive creates exhaustion.

- If they are healthy and sufficient in supplies, attack their supplies.

- When they are on defense, attack a vital target to ensure their offense.

2) Be formless. You attack where they are not so they don’t know where to defend. You defend by laying low so they don’t know where to attack. When you are formless, your opponent will not be able to generate intelligence and cannot adapt.

- This will confuse the opponent. They will become wary of your strategies and reluctant to engage in conflict.

3) Attack what is dear to them. If your opponent attempts to be formless, draw them out by attacking what is dear to them. They will not be able to resist defending and rescuing what is important to them.

- When you force your enemy to take a form while remaining formless, they will naturally spread themselves thin to cover all bases.

- While they are occupied with that, you remain intact and fully manned. Once they are divided, your consolidated strength can attack their divided strength.

- The more defensive positions you manipulate your enemy into establishing, the more diminished their power will become.

4) Be prepared. You must be the designer of the when and how of battle. If you always know when and where the fight will take place, you can always be prepared. In not knowing the logistics of the battle, your opponent will be overly alert, wear themselves down, and be unable to form a strategy. This was key during the Warring States Period.

- If you do not know when and where the fight will take place, even if you are stronger, you are at a disadvantage and victory is uncertain. Therefore, if the battleground is unknown, do not fight.

5) Be adaptable. It has been said that military force is like water: like the flow of water is determined by the terrain, the force of military action is determined by the opponent. The ability to shapeshift according to the actions of your opponent is intelligence. When the enemy is to blame for your victory, it is genius.

6) Don’t let your strategy get out. If the enemy knows where you will strike, they will amass their powers to oppose you there. Similarly, if you show your hand by adopting a form, your opponent will be able to see where you are strong and where you are vulnerable.

The Qi were masters at these strategies during the Warring States Period, which led to their eventual victory.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Art of War" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Art of War summary :

- How to mislead your enemies to win the war

- Classic examples from Chinese history to illustrate Sun Tzu's strategies

- How to use spies to gather information and defeat your opponents