This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Walden" by Henry David Thoreau. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s voluntary poverty? What was Henry David Thoreau’s attitude toward poverty and charity?

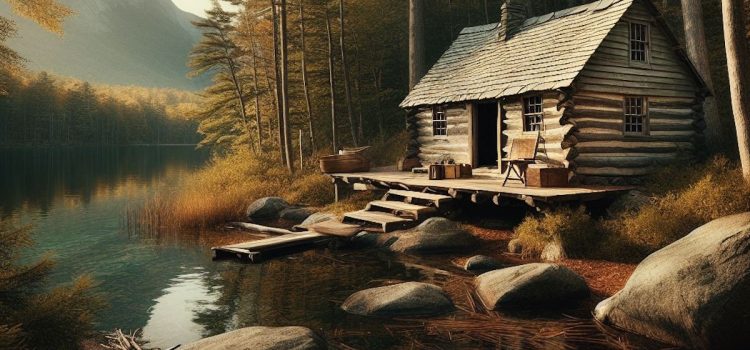

Henry David Thoreau’s simplicity is a major theme of Walden. During the time he lived in the modest cabin in the woods, he practiced voluntary poverty—stripping down his life to the bare necessities to fit the lifestyle he chose.

Continue reading to learn about Thoreau’s practice of voluntary poverty and a bit about his attitude toward people who lived in poverty.

Thoreau’s Simplicity and Voluntary Poverty

Thoreau explains that the choices he made in moving to Walden were motivated by a desire to live more simply—and he doesn’t hesitate to say that he thinks his readers should simplify their lives, too. During the two years he lived in the woods, Thoreau’s simplicity manifested in what he calls a life of “voluntary poverty.” He reduced what he produced and consumed to just what was necessary for survival: food, shelter, clothing, and fuel.

(Shortform note: True to its name, Thoreau’s “voluntary poverty” was a choice. He came from a middle-class family, and he could afford to supplement the crops he grew with store-bought goods. He could also leave Walden when he felt like it. Some scholars argue that Thoreau was aware of the irony of his choosing a lifestyle that was imposed on others. But he also believed that it was important for people who had his advantages to recognize what life was like for the disadvantaged. He contended that by stopping our endless pursuit of material things, we can pay attention to what life is like for others.)

While Thoreau believed there is dignity in labor and in working to provide for oneself, he contended that people consume too much and work too much to pay for it. He explains that people can live on much less than they think possible. Then, with that change in perspective, they can stop overworking themselves to afford a large home, a vast family farm, fashionable clothes, or even an expensive education. Thoreau contends that the drive to acquire these and other material things results in unacceptable costs in terms of time: time that we give up for truly living in order to obtain possessions that aren’t necessary and don’t fulfill us.

(Shortform note: Thoreau’s reservations about exchanging our time for our necessities, homes, and material possessions seem to anticipate modern concerns about the trap of the middle class. In Having and Being Had, Eula Biss writes that we buy into the values of the capitalist system that determines what our time is worth in terms of the money and things for which it can be exchanged. Life under such an economic system is compromised and frustrating, Biss explains. But few of us can figure out how to disentangle ourselves from the system—even Thoreau couldn’t withdraw himself completely from the modern economy.)

Thoreau’s Interactions With Others Who Lived in Poverty

At Walden, Thoreau enjoyed visits from people who lived in poverty or were labeled unintelligent. He writes that, when he engaged them in conversation, they often demonstrated wisdom that far exceeded that of the people who had dismissed them. Thoreau explains that he enjoyed the company of people who visited the woods with the intention of really leaving the preoccupations of the city behind them. However, he encountered some people whom he chose to turn away, including those whom he characterized as simply seeking charity.

(Shortform note: Some critics say that Thoreau romanticized poverty but felt inconvenienced by people experiencing poverty. He declined to engage in philanthropy, writing that it didn’t agree with his constitution. Some readers think this fault undermines Thoreau’s entire mission at Walden. These critics say that the point of engaging in self-reflection and learning from the natural world is to become a better person and that Thoreau fails that test. Yet, Thoreau has been accused of hypocrisy since before Walden published—and many have found his failure to perfectly practice what he preached condescending. But biographers say that he was full of contradictions—some of which might have a good explanation and some of which might not.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Henry David Thoreau's "Walden" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Walden summary:

- The philosophy behind Henry David Thoreau's classic novel

- How you can build a meaningful life by living in harmony with nature

- A look at how Thoreau spent his time at Walden Pond, outside the book