This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Tipping Point" by Malcolm Gladwell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What does “channel capacity” mean? How much information is the brain able to store? What does this mean about the number of relationships we’re able to maintain?

Channel capacity is a term in cognitive psychology that says humans have limited space in our brains for certain kinds of information: by and large, we can only remember six or seven things — whether objects, numbers, categories, or sounds — before we get overwhelmed and start to lose track. Similarly, social channel capacity states that we have a limited emotional capacity. We can only maintain deep relationships with a limited number of people before we hit our limit.

We’ll cover how social channel capacity works and why we function better in small groups.

Social Channel Capacity: In Groups, Less is More

Define channel capacity: Every species has a limited capacity for how much information individuals can store, including how many close relationships they can maintain. This is the social channel capacity definition.

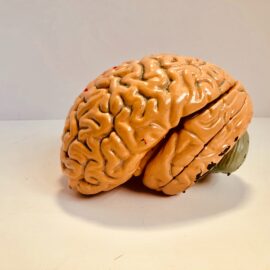

The concept of channel capacity was developed as anthropologist Robin Dunbar noted the difference in brain size of various primates (including humans). Specifically, compared to other mammals, primates have an exceptionally large neocortex. The neocortex is the part of the brain responsible for complex thought and reasoning.

Primates with a larger neocortex live in larger groups, with humans having the largest of all in both categories (neocortex and community size). Dunbar argued that a large neocortex is necessary to handle the complexities of larger groups; the more people (or primates) in a group, the more relationships and dynamics you have to keep track of.

- (Shortform example: In your circle of friends, you know which people have close personal bonds, which people only see each other in group settings, and which people have a history of conflict. The same is probably true (at least to some extent) among your coworkers.)

The power of peer influence is strongest in groups that are small enough where each member has some kind of acquaintanceship or relationship with the rest of the group. This group dynamic makes small groups ideal for influencing behavior to tip an epidemic. Social channel capacity means less is more.

Social Channel Capacity Example: The Methodist Church

The founder of the Methodist church, John Wesley, created an epidemic by mobilizing many small groups throughout England and North America, expanding the religion from 20,000 to 90,000 followers within six years. This is a great social channel capacity example.

Wesley traveled around England and North America preaching open-air sermons to thousands of people. In each place, he would stay long enough to form religious societies from his most zealous followers. Converts had to attend weekly meetings and follow a strict code of conduct, or else face expulsion from the group. This way, each group self-regulated and maintained the principles of the faith.

In his travels, Wesley regularly visited these societies to reinforce the structure and ensure the standards of the religion remained strong. But overall, the groups he’d created became communities that largely kept themselves in line.

The Rule of 150

On a community level, people have a capacity to have some kind of social relationship with about 150 people. In different cultures and organizations — from tribes to military divisions — people have organically realized that social structure functions best at or under 150 people. This is called the Rule of 150. This is another iteration of the social channel capacity.

In a community of 150 or less, people know everyone well enough to keep each other accountable to get work done, to abide by social standards, and to follow other group policies and norms. Groups of this size are better able to reach consensus and act as one. Beyond that limit, smaller groups start to break off and organizational hierarchies (e.g. management structures in companies) may be needed to keep order.

Groups also use a joint memory system called transactive memory to act more efficiently and cohesively. People are not limited to the facts and information we can memorize; we remember the sources of useful information — like phone books and maps and recipe books — to give us access to much more than our memory can hold. When we rely on the people we have close relationships with to hold information for us, this is called transactive memory. This is the result of our social channel capacity.

Couples and families do this often. If you’re talking about a movie you saw and can’t remember an actor’s name, you may turn to your spouse to help you fill in the missing information because she tends to be better at remembering those kinds of details. Or if you just came home with a new tech device and don’t know how to program it, you know your teenage daughter is the best person in your family to ask for help.

In this way, groups develop a joint memory system in which each person organically becomes the resident expert on one topic or another, based on who is best suited to remember that kind of information. Transactive memory makes groups more efficient because each person does not need to know a little bit of everything. Instead, she just needs to know who has the expertise she needs. For this to work, the group must be small enough that the members know each other well enough to know who knows what, and to trust each other to be proficient and reliable within their individual areas of expertise.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Tipping Point" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Tipping Point summary :

- What makes some movements tip into social epidemics

- The 3 key types of people you need on your side

- How to cause tipping points in business and life