This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" by Rebecca Skloot. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Who was the gynecologist that excised tissue from Henrietta Lacks? Why did Richard Wesley TeLinde want her cells? How did TeLinde use the cells for research?

Richard Wesley TeLinde was a well-known gynecologist and the superior of the doctor treating Henrietta Lacks at Johns Hopkins. Dr. TeLinde was interested in the treatment and progression of carcinoma in situ, meaning noninvasive carcinoma.

Learn about how Richard Wesley TeLinde’s research interests changed the course of science.

Henrietta Lacks Arrives at Hopkins

Henrietta visited Johns Hopkins, where she was seen by a gynecologist named Howard Jones. Jones discovered in Lacks’s medical history an array of un- or undertreated illnesses, including asymptomatic neurosyphilis and gonorrhea. There was also abnormal vaginal bleeding and blood in Henrietta’s urine after her last two pregnancies.

Upon examining Henrietta, Jones quickly located the lump, whose color and consistency was unlike any other lesion he’d seen (he described it in his notes as “grape Jello”) Even though Joseph had been delivered at Hopkins scant months before, no one had noted any sort of cervical abnormality, either upon delivery or at Henrietta’s six-week checkup. Which meant the lump had grown exponentially in just three months.

A few days later, Jones received Henrietta’s biopsy results. The pathologists had found Stage 1 epidermoid carcinoma.

Hopkins: A Hub of Cancer Research

Coincidentally, Jones and his superior, an internationally renowned gynecologist named Richard Wesley TeLinde, were currently researching cervical cancer. TeLinde had become a controversial figure among gynecologists due to his aggressive treatment of carcinoma in situ, meaning of “noninvasive” carcinomas, which are carcinomas that grow on the surface of the cervix (carcinomas that penetrate the cervix are “invasive”). Whereas most gynecologists in the field believed noninvasive carcinomas would stay on the surface of the cervix and remain nonfatal, TeLinde believed cells could become invasive from carcinoma in situ, meaning he often treated them by removing the cervix, uterus, and part of the vagina.

Part of the reason there was disagreement about how to treat noninvasive carcinoma was that it was a relatively new field. Only ten years before Henrietta Lacks saw Howard Jones, a Greek researcher named George Papanicolaou had developed a test—now known as a Pap smear—that enabled doctors to diagnose carcinoma in situ.

TeLinde Studies Noninvasive Carcinoma

Determined to prove the danger of carcinoma in situ, meaning it could morph into invasive carcinoma, Richard Wesley TeLinde embarked on an ambitious study around the time Henrietta first visited Hopkins: He and his team compiled and reviewed the medical records of every Hopkins patient in the past ten years that had been diagnosed with invasive carcinoma to see if noninvasive carcinomas had been present first. Many of the patients in the study were included without their consent: The logic was that patients being treated for free in the public wards—largely African-Americans—“paid” for their treatment by being available to researchers as subjects (again, without their knowledge).

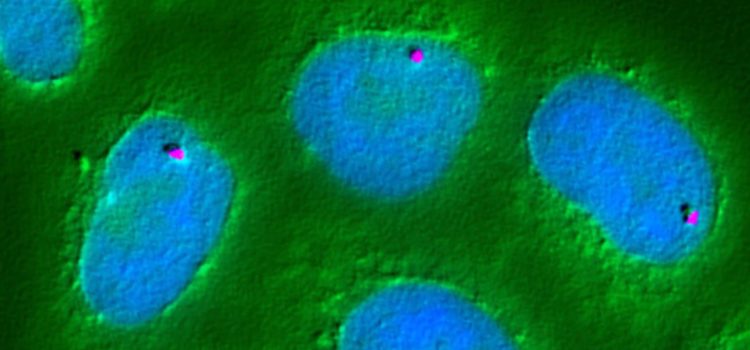

TeLinde’s study found that 62% of patients diagnosed with invasive cancer had tested positive for carcinoma in situ first, proving his hunch correct. But he wanted to seal his argument by comparing healthy cervical cells with both invasive and noninvasive carcinoma cells. If he proved that invasive and noninvasive carcinoma cells behaved similarly in the laboratory, he would have an open-and-shut case for treating them similarly as well. So he cut a deal with a tissue researcher at Hopkins named George Gey (pronounced like “guy”): If Richard Wesley TeLinde provided Gey with tissue samples to experiment with, Gey would try to grow them in the lab he operated alongside his wife, a surgical nurse named Margaret.

Henrietta’s Cells Excised

Henrietta, unbeknownst to her, became one of Richard Wesley TeLinde’s and the Geys’ subjects. When she returned to the hospital after receiving her diagnosis—rather than tell Day or her family that she’d been diagnosed with a malignant tumor, she simply told them the doctors needed to evaluate her and give her some medicine—she signed a consent form to be operated on, was subjected to a battery of tests, and eventually treated with radium, the gold standard for cancer treatment at the time. (It was later discovered to cause cancer itself.) Before her surgeon applied the radium to her cervix, however, he took a small sample of both healthy tissue and cancerous tissue and sent it off to the Geys’ lab.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Rebecca Skloot's "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks summary :

- How Henrietta's cells became used in thousands of labs worldwide

- The complications of Henrietta's lack of consent

- How the Lacks family is coping with the impact of Henrietta's legacy