This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Body Keeps The Score" by Bessel van der Kolk. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Is PTSD common in veterans? What are PTSD symptoms in veterans and when was it first discovered?

Combat PTSD in veterans went by several different names before being called PTSD. However, medical professionals realized that veterans returning from war experienced symptoms related to what they experienced.

Read more about combat PTSD, veterans, and how the disorder was first identified.

PTSD in Veterans

Early in the author’s career, he worked as a staff psychiatrist at the Boston Veterans Administration Clinic. There van der Kolk met a man named Tom who had served in Vietnam with the Marines 10 years earlier and, despite now having a beautiful family and successful law practice, was struggling with alcoholism, bouts of rage and feelings of inner torment.

Tom constantly had nightmares of the ambush he experienced in Vietnam, during which everyone in his platoon was killed or wounded. Afraid of the nightmares, Tom would stay up most of the night drinking to dull his pain and memories. He was easily upset and worried about getting angry around his family, because he had trouble controlling his actions. The only things that seemed to bring Tom some sense of calm was either speeding dangerously on his motorcycle or drinking heavily.

As the author listened to Tom explain his background and his current suffering, the author wondered how and why people who experienced trauma remain seemingly trapped in the past, constantly reliving the traumatic event. This is an example of PTSD in veterans.

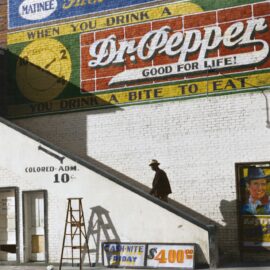

It was 1978, and van der Kolk struggled to find much medical literature explaining Tom’s and other veterans’ symptoms, which were historically diagnosed as war neurosis, shell shock, or battle fatigue. He finally found a book that seemed to shed some light; The Traumatic Neuroses of War, which psychiatrist Abram Kardiner published in 1941, described “traumatic neuroses” that caused a chronic hypervigilance to threat. Kardiner’s book explained that traumatic neuroses — which today we’d call posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — has a physiological basis, meaning that the symptoms come from the body’s response to the original trauma. In other words, the effects aren’t not just in sufferers’ heads, but also in their bodies.

Diagnosing PTSD

Before 1980, the symptoms of PTSD were described and diagnosed separately — as depression, mood disorders, alcoholism, substance abuse, and schizophrenia. A turning point came when a group of Vietnam veterans and psychoanalysts Chaim Shatan and Robert J. Lifton lobbied the American Psychiatric Association to create a diagnosis called posttraumatic stress disorder, which included a cluster of symptoms.

PTSD is defined as the result of a horrendous event involving death, serious injury — or the threat of either — to the patient or someone else, causing intense feelings of fear and helplessness. Symptoms of PTSD include flashbacks; nightmares; avoidance of people, places, or thoughts connected to the trauma; and hyperarousal, including hypervigilance, insomnia, and irritability. PTSD in veterans was one of the first recognized forms of PTSD.

Once the diagnosis was created, this opened the door for new research, understanding, and approaches to treatment.

Soon after, in 1982, van der Kolk started working at the Massachusetts Health Center, a Harvard teaching hospital. While working there, he encountered dozens of female patients who had been sexually abused as children.

At the time, psychiatry textbooks stated that incest was not only extremely rare in the United States, but also that it “diminishes the subject’s chance of psychosis and allows for a better adjustment to the external world” — the textbooks were saying that assault survivors were not only unharmed, but better able to cope in the world. In sharp contrast, van der Kolk found the opposite to be true: His patients suffered nightmares and flashbacks, intense rage, periods of emotional collapse, and difficulty maintaining meaningful relationships.

These patients reminded van der Kolk of the veterans he had worked with previously, and he realized that trauma could be caused by much more than battlefield tragedies. Violent crimes, rape, and abuse could bring on many of the the same symptoms of combat PTSD visible in veterans — and for child victims who experience these traumas in their homes, the source of their suffering is not a foreign enemy but their caretakers.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Bessel van der Kolk's "The Body Keeps The Score" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Body Keeps The Score summary :

- How your past trauma might change your brain and body

- What you can do to help your brain and body heal

- Why some trauma survivors can't recognize themselves in the mirror