This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Rationality" by Steven Pinker. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Do you ever confuse correlation with causation? How can you accurately determine the cause of something?

In Rationality, Steven Pinker examines why people make irrational decisions. Often, people run into problems when considering causation and correlation. He explains how to avoid the trap of linking them when they’re not connected and offers some tips on how to determine actual causes.

Continue reading to understand why correlation doesn’t equal causation.

Correlation Doesn’t Equal Causation

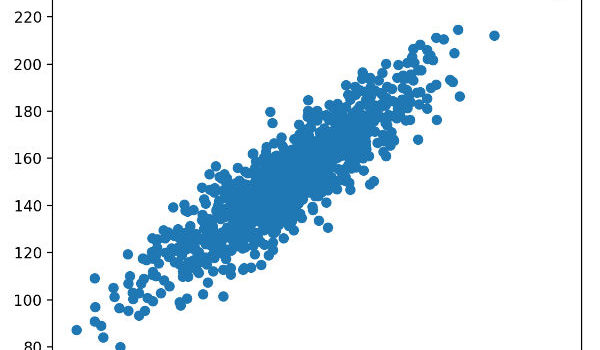

A common mistake people make is thinking that events that are correlated (they often happen at the same time) are causing each other, when in fact they might be linked simply by coincidence or by a third factor. The failure to understand that correlation doesn’t equal causation can lead people to make poor decisions; when they think the wrong event causes another, they incorrectly predict the future.

For example, if the stock price of a company always rises in November, a person might think the arrival of November causes the price to rise, and they might then buy stock in October in anticipation of that rise. However, if the true reason behind the price increase is that the stock rises when the company offers a huge sale on their goods, which they happen to always offer in November, then the person buying stock in October might lose money if the company decides not to offer that sale this particular November. If the person had correctly identified the causal link (between the sale and the price rise, instead of between the month and the price rise), they might have purchased their stock at a better time.

Pinker notes that it can be difficult to determine causation, especially when there are multiple events or characteristics to account for. Complicating matters is that, very often, correlation does imply some sort of causation: If two events are commonly linked, they likely have a common source (as in the stock price example above).

| How Our Search for Meaning Misleads Us In Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb argues that one reason people confuse correlation with causation is that humans are wired to seek meaning, which drives us to invent meaning when we see patterns of events. This can lead us to mistake correlations that are due to either random chance or a third factor that’s not as easy to detect. This can be a particularly easy trap to fall into if the events we’re studying are closely related in theme as well as in timing, as this often indicates a common source. For example, eating ice cream and getting sunburned are both related to hot afternoons. However, if you get a sunburn every time you eat ice cream, it’s not the ice cream that’s causing your burn—it’s the common source of both events: the hot sun. |

When determining what factors cause other factors and which are merely correlated, Pinker notes that you can do one of two things:

- Run experiments.

- Analyze data.

Experiment to Determine Causation

Pinker recommends running a “natural experiment” to identify which events cause other events. To do so, you’d divide a sample population into two groups, change some characteristics in one group, and see how (or if) those changes affect the situation for that group. Such experiments are excellent ways to measure precisely how a factor might affect change and to determine which might only be correlated with other factors.

There are limits to these experiments, though. You might fail to account for variables that affect your results (if you’re studying mostly young adults, for example, you might miss how a change would affect a broader population), and there are ethical limits to how much you can change real-world elements. You can’t, for example, force two countries to go to war just so you can examine the effects on food pricing.

| Natural, Field, and Lab Experiments Pinker calls these “natural experiments,” but some psychologists call this type of experiment a “field experiment,” and they have a different meaning for the term “natural” experiment.” A field experiment is conducted by changing some aspect of a natural setting, in the way Pinker describes, but a “natural” experiment, as defined by other psychologists, doesn’t deliberately manipulate a variable, but instead tracks the effects of a change that’s already happening in a natural setting. For example, you might track how a change to minimum wage influences retail prices in one state versus another, where the wage didn’t increase. This differs from Pinker’s description of purposefully changing a variable and seeing its effects. Psychologists also name a third type of experiment that Pinker doesn’t discuss—a lab experiment, which is conducted in a controlled environment rather than in a real-world setting like a field experiment or natural experiment. Each of these three types of experiments gives a researcher different levels of control as well as different levels of accuracy—in a lab experiment, a researcher has more control over the variables but might end up with a less accurate reflection of how a change would affect a group of people in the real world. Natural and field experiments might produce more accurate results, but they give the researcher less control over variables and changes. |

Analyze Data to Determine Causation

When you can’t run an experiment, you can look for patterns in existing sets of data that might shed light on how one factor affects another. Pinker mentions two factors in particular that you should analyze data for when determining causation: chronology and nuisance variables.

Chronology: You can often judge which factors affect others, and not in reverse, by noting which factors occurred first. For example, in economic data, if prices across multiple countries rise before wages rise, but wages never rise before prices rise, that indicates that price increases drive wage increases and not the reverse.

(Shortform note: Chronology can help identify causation but isn’t foolproof. In Fooled by Randomness, Taleb notes the danger of analyzing data for patterns like chronology, arguing that given a large data set, you can always find some patterns if you look hard enough. He calls this “data mining,” and writes that we can ascribe meaning to such coincidences even though their true cause is chance. He cites, as an example, books that claim to show that the Bible predicted events. If you search among all events that have happened since the publication of the Bible, you’re sure to find ones that have some discernible connection to Bible verses. But, the chronology of the Bible preceding these events doesn’t prove it predicted them.)

Nuisance variables: You can control for factors that are associated with events but don’t cause them (nuisance variables) by matching such factors in different contexts and looking at how other data changes within those matched sets. For example, if you’re examining how alcohol consumption affects longevity, you might want to consider how exercise might skew your results. You could examine two groups of people, one that drinks and one that doesn’t, and match up individuals from both groups who also exercise. Any differences in longevity would then not be due to differences in exercise but would be more closely related to alcohol consumption.

(Shortform note: Nuisance variables can create what Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass Sunstein call “noise.” In Noise, they define the phenomenon as unwanted variations in events that can impair our judgments—for example, stock prices that jump higher and lower in small amounts and encourage people to buy and sell repeatedly, and that obscure the longer-term trajectory of the price. Nuisance variables, as tangential factors that introduce variation into events, can create such noise and cause people to miss important data they’d be better off paying attention to.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Steven Pinker's "Rationality" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Rationality summary:

- Why rationality and reason are essential for improving our world and society

- How you can be more rational and make better decisions

- How to avoid the logical fallacies people often fall victim to