This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Your Inner Fish" by Neil Shubin. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

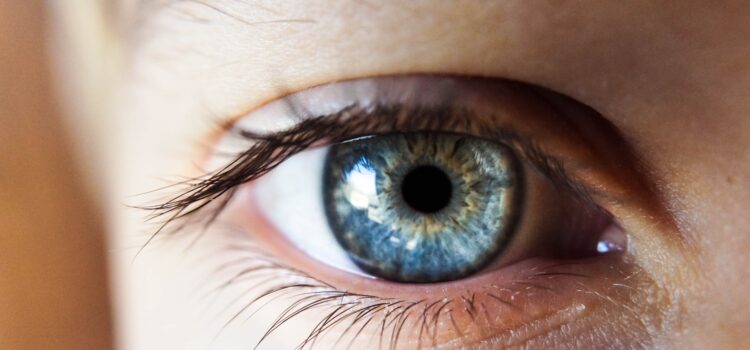

How did human eyesight form? How do our eyes work and how does it connect to human evolution?

Human eyesight formed as humans evolved from our ancestors. The way our eyes work is a complicated process, and we can get clues on how it came to be from many creatures—including the most ancient ones that contributed to forming human vision.

Read more about human eyesight and how it evolved over time.

Developing Human Eyesight

How does human eyesight work? This explains and and traces the history of their component parts—this history stretches back to some ancient creatures including flies, jellyfish, and worms. Understanding how our eyes evolved can help answer the question “how do our eyes work?

Animals use many different tissues and organs to see, or capture light—for example:

- Invertebrates use simple photoreceptor organs

- Insects have compound eyes

- Humans have camera-type eyes

Studying different types of eyes suggests how humans’ ability to see developed. The development of the human eye can be compared to that of a car. The creation of parts such as tires and engine components are part of the development of the car as a whole. Our eyes have a history—as an organ and as component parts: cells, tissues, and genes. Studying that history reveals we’re an amalgam of pieces of other creatures.

How Do Our Eyes Work? The Science of Human Eyesight

Eyes capture light that’s sent to the brain for interpreting as an image.

Human eyes, like those of most animals, are like cameras. Light entering the eye is focused on a screen (the retina) in the back of the eye, which sends signals to the brain. But first, light travels through several layers: the cornea, iris (which controls the amount of light), and then the lens, which focuses the image. This is part of how human eyesight works.

In human vision, the retina has two types of light receptor cells that send signals to the brain: the most sensitive receptors see black and white, while less sensitive receptors see color. About 70% of our body’s sensory cells are light receptor cells, which shows how important human vision is to us.

From fish to mammals, most animals with a skull have this camera-like eye. Other creatures have eyes ranging from light-detecting patches, to eyes with compound lenses, to early versions of the camera eye.

We can learn about human eye development by comparing how three structures differ between human eyesight and other types of eyes:

- The molecules that gather light

- The eye tissues

- The genes that direct eye development

1) Light-Gathering Molecules

The molecule in the eye that collects light breaks into two parts after absorbing light: Vitamin A and a protein called an opsin that starts a chain reaction sending an impulse to the brain for human vision.

Humans, like all animals, need three different opsins to see color and one to see in black and white. Every animal that can see light (including humans, insects, clams, and scallops) uses the same kind of opsin molecule to do so.

Opsins transmit messages by carrying a chemical across the membrane of a cell, then helping the chemical follow a convoluted path through the cell to the nucleus. This same tortuous path exists in certain molecules in bacteria, meaning that, in a sense, we have modified pieces of an ancient bacteria inside our retinas, helping us see. This is part of how human vision works.

Examining opsins and eye development in different animals—for instance, the development of color vision in primates—offers further clues to human eye development.

Primates’ (and humans’) vivid color vision comes from a change in the gene that makes light receptor molecules. Primates have three light receptors tuned to different kinds of light, while most other mammals have two.

The two kinds of receptors in most mammals are made by two kinds of genes. Primates apparently copied one of these two genes to improve their vision, just as mammals copied odor genes to develop a more acute sense of smell. The mutation likely helped them pick the most colorful (and therefore nutritious) fruit from among different kinds as plant life grew more diverse.

2) Eye Tissues

There are two basic eye types: those of invertebrates and vertebrates. Each type has a different way of increasing the light-gathering surface area of the eye tissue. Tissue in eyes of invertebrates such as flies and worms has many folds, while in vertebrate eyes, there are bristles projecting from the surface area.

Scientists found a connection between our eyes and invertebrate eyes in 2001, while studying the eyes of a polychaete or primitive worm. Although primitive, polychaetes have two types of light-sensing organs: an eye plus light-sensing patches under their skin.

Researchers discovered that worm’s eye is a normal invertebrate eye, but the light-sensing patches have the opsins found in vertebrate eyes. Further, the patches have primitive versions of the bristles in vertebrate eyes. The polychaete is a link between invertebrate and vertebrate eyes.

3) Genes that Direct Eye Development

Eyes that look entirely different—for instance, those of worms, flies, and mice—are nonetheless closely related because they share a common genetic recipe for building eyes like those in human vision.

In the early 1900s, scientists studying a mutation that made flies eyeless learned that a similar mutation in mice and humans causes the same type of problems—individuals with the mutation lack large portions of eye tissues.

Also in the 1990s, other researchers found that flies, mice, and humans with the mutation had similar DNA sequences on a specific gene, which they were able to isolate (this meant that a normal version controlled the development of eyes). They experimented with turning the gene, called Pax 6, on and off. Inserting it in flies resulted in eyes growing all over the flies’ bodies. A mouse version of the gene created an eye on a fly’s body by triggering a chain of gene activity in fly cells.

Thus, the Pax 6 gene directs the development of eyes in all animals. Eyes of different animals may look quite different, but the genetic activity behind them is the same.

So like the parts of a car, the parts of our eyes have different histories. The molecules, tissues, and genes in human eyes are derived from microbes, worms, and flies that all worked to create human eyesight.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Neil Shubin's "Your Inner Fish" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Your Inner Fish summary :

- How your hands and feet are like a fish that lived hundreds of millions of years ago

- How the structure of your head can be traced back to an ancient, headless worms

- What parts of your body are uniquely human