This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Influence" by Robert B. Cialdini. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Have you ever done anything out of obedience to authority or a sense of duty? Did it ever make you uncomfortable? Would you question the instructions of someone in a position of authority? The Milgram Shock Experiment shows how far you might go.

The Milgram Shock Experiment is a study that demonstrated how willing people are to give deference to authority. Their obedience to authority allowed them to inflict pain on others even when they felt uncomfortable.

See how a sense of duty played out in the Milgram Shock Experiment.

What Is the Authority Principle?

The Authority Principle states that people are hard-wired to comply with requests that come from an acknowledged and accepted source of authority. Thus, we are strongly inclined to be deferential to people who we consider to be in a position of power or expertise. Examples would include teachers, members of the armed forces, police officers, doctors, and judges, to name just a few.

Of course, there are good and legitimate reasons why we’re strongly conditioned to obey authority. Leadership, hierarchy, and authority are obviously necessary ingredients in any functioning society. Unfortunately, authority can also be abused and exploited.

The Milgram Experiment: A “Shocking” Deference to Authority

Just how deep does our obedience to authority run? What can normal human beings be compelled to do at the behest of an authority figure? The results of the (in)famous experiment conducted by Stanley Milgram at Yale in 1961 demonstrated just how far authority can be used—and abused.

The test subjects were told that they were participating in an experiment to measure the effects of punishment on learning and memory. One set of participants (the Learners) was tasked with memorizing lists of words. The other set of participants (the Teachers) had to measure the Learners’ progress and administer electric shocks to the Learners whenever the latter made a mistake. The lab-coated researcher was always present to ensure that both the Teacher and the Learner carried out their assigned responsibilities.

Inflicting Pain

The Learners, however, weren’t really test subjects, but were instead hired actors. And there was no real electric shock being delivered. But the Teachers didn’t know this: they believed they were delivering real shocks to real people.

The Milgram Shock Experiment was really measuring obedience to authority with people’s willingness to inflict pain on others if it was part of their “job.” At first, the Teachers were told they were administering mild shocks to the Learners, akin perhaps to the static electricity you might feel when you open a doorknob after walking on a carpet.

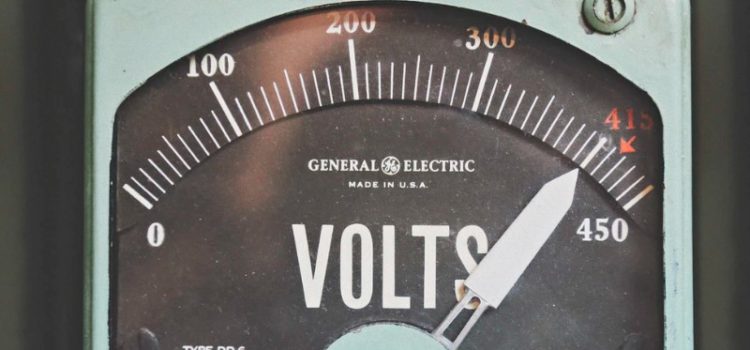

But for every wrong answer, the Teachers were told to increase the intensity of the shocks by 15 volts. By the fourth or fifth administration, the shocks were clearly painful.

Refusing to Quit

Yet, the deference to authority persisted and Teachers continued to administer them, even when they themselves were clearly distraught at the idea of having to inflict severe pain on someone else.

They might glance over nervously at the researcher leading the Milgram Shock Experiment. But the researcher would only order the shocks to continue, in a series of increasingly harsh commands:

- “Please continue.”

- “The experiment requires that you continue.”

- “It is absolutely essential that you continue.”

- “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

As a result, the Teacher would dutifully, if reluctantly, carry on with the task. Of the 40 Teachers, not a single one refused to continue the shocks when the victim begged to be released. Only when the victims began to scream in agony and/or show signs of unconsciousness or heart failure did any of the Teachers quit—and even then it was a distinct minority.

Sense of Duty

Milgram was shocked at the deference to authority and how willing his subjects were to carry on with their task as long as there was an authority figure (the stern-faced researcher in the lab coat) urging them on.

There was nothing particularly special about the group of people selected to be Teachers in the Milgram Shock Experiment: they were chosen randomly and represented a broad cross-section of ages, occupations, and educational levels. In repeated trials, Milgram found that people of all backgrounds, and of both sexes, were equally willing to administer the shocks: it was a universal characteristic.

Variations on the Milgram Shock Experiment honed in on the authority of the researcher being the decisive factor. In one twist, the researcher and the Learner switched scripts: the lab-coated researcher ordered the Teacher to stop administering the shocks, while the Learner insisted on carrying through with the experiment. 100 percent of the Teachers stopped administering the shocks when the person asking them to continue was merely an equal instead of a superior.

Similarly, when the researcher was receiving the shocks and begged to be released, all of the Teachers refused to administer any more. From the Milgram Shock Experiment, researchers concluded that the sense of duty to an acknowledged authority figure was compelling enough to drive the test subjects to inflict excruciating pain on others.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Robert B. Cialdini's "Influence" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Influence summary :

- How professional manipulators use your psychology against you

- The six key biases you need to be aware of

- How learning your own biases will help you beat the con men around you