This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Black Like Me" by John Howard Griffin. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is the cycle of oppression? What are the four steps of the cycle? What was racial oppression like in 1950s America?

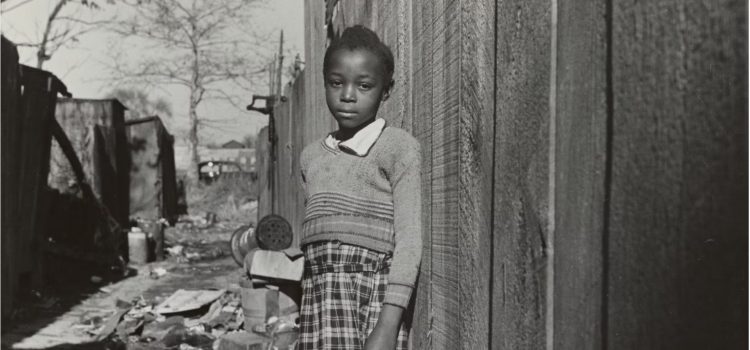

In 1959, John Howard Griffin wrote Black Like Me to convince white Americans that the U.S. was not the racism-free country they thought it was. The book describes Griffin’s account of the segregated South and the cycle of oppression faced by Black Southerners.

Read on to learn more about the cycle of oppression in the 1950s, according to Griffin.

What is the Cycle of Oppression?

In Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin argues that it was challenging for Black people to escape anti-black stereotypes because these stereotypes trapped them in a vicious cycle of oppression. Let’s break down the steps of this cycle as Griffin sees them.

Step 1: Oppression. Systemic racism deprived Black people of dignity and opportunities to thrive.

Step 2: Violence and escape. According to Griffin, many Black Southerners engaged in “immoral” behavior because systemic racism robbed them of opportunities, dignity, and power. He explains that their anger about this racism often turned to violence, and they found refuge in physical forms of escape (such as sex and drugs). Griffin argues that these behaviors weren’t evidence that Black people were innately violent and indulgent—rather, these behaviors reflected the harmful circumstances of oppression and what it pushed Black people to do.

Step 3: Stereotype formation. White people mistakenly assumed that Black people’s “immoral” behaviors reflected their innate characteristics, rather than the circumstances of oppression. As a result, white people formed and perpetuated antiblack stereotypes.

Step 4: Further oppression. White people used racist stereotypes as evidence that Black people were inferior and didn’t deserve the same civil rights and opportunities as white people. This further perpetuated Black people’s oppression—and it strengthened these stereotypes. The cycle continued, making it increasingly hard for Black people to escape these stereotypes (and racial oppression more generally).

Oppressive Double Binds

One philosophy professor argues that double binds are a feature of all forms of oppression. She defines an “oppressive double bind” as a situation in which you have two choices—to resist your oppression or not—and either way, you reinforce your own oppression. If you choose to stay silent about your oppression, it continues. But if you do speak up, you face oppression for speaking up.

For example, imagine you’re a gay man who’s stereotyped and harassed for being “oversensitive.” If you say nothing, your harassers won’t stop. But if you do speak up, your harassers may interpret your complaints as further evidence that you’re oversensitive.

The philosophy professor argues that because oppressive double binds constrain your options, you should forgive yourself for having to make “imperfect choices.” You shouldn’t be overly self-critical when you choose to be silent about your oppression or resist it. Instead, you should recognize that when you face oppression, your choices are constrained and there’s no perfect option.

For instance, the gay man might choose to be silent to protect himself—or he might choose to speak up so he has the satisfaction of being courageous. Both choices are imperfect because neither leads to the ultimate goal—complete freedom from oppression. However, the man should forgive himself for making either choice because it’s not his fault that homophobia put him into an oppressive double bind.

| Modern-Day Experts’ Ideas on Racial Oppression Ideas from today’s experts on racism both overlap with and differ from the ideas Griffin expresses about the cycle of oppression. Let’s compare and contrast their perspectives with each of the steps in Griffin’s cycle. Step 1: Oppression. In Black Like Me, Griffin mostly explores the oppression faced by Black men. As Ijeoma Oluo explains in So You Want to Talk About Race, the concept of intersectionality recognizes that someone who has more than one marginalized identity may experience racism differently. Therefore, a Black woman may experience Griffin’s cycle of oppression differently than a Black man might since she experiences both racism and sexism. For instance, some writers claim that Black women experience the effects of colorism more than Black men do because colorism closely involves beauty standards and women face extra pressure to be beautiful. Step 2: Violence and escape. Griffin’s idea that oppression leads Black people to engage in immoral behavior is an example of what Ibram X. Kendi calls the “oppression-inferiority thesis” in How to Be An Antiracist. This is the idea that oppressive systems make you inferior. Kendi traces the root of this idea to the 19th century when abolitionists were trying to end slavery. Some abolitionists tried to persuade people to join their efforts by claiming that Black people weren’t naturally inferior—rather, slavery had made them behave in inferior ways. Kendi claims that this oppression-inferiority thesis, while well-intentioned, is nonetheless a racist idea because it’s still rooted in the belief that one racial group is inferior to another. Step 3: Stereotype formation. In Biased, psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt explains that some stereotypes take the form of implicit biases: unconscious biases we form when we associate a group of people with the category of “good” or “bad.” People with antiblack implicit biases sometimes unknowingly perpetuate antiblack stereotypes. Eberhart claims that there are ways for white people to recognize and put an end to these unconscious racial biases. One strategy is to seek out and listen to stories of others’ experiences with racism. As you empathize with storytellers, you develop an awareness of your own biases. A recent study found that empathy exercises such as this can reduce teachers’ antiblack bias. Step 4: Further oppression. Psychologists emphasize that social roles factor into cycles of oppression. Due to stereotypes, people are more likely to fulfill some social roles over others, and those roles then reinforce the stereotypes that landed them there. This can make it hard for people to adopt social roles beyond those they’re stereotyped to have. For example, the stereotype that girls aren’t good at math and science may reduce the number of female scientists, and the low number of female scientists may further perpetuate the stereotype that girls aren’t good at math and science. According to some psychologists, policies that ensure people are equally distributed among social roles can uproot these stereotypes. |

The Role of the Southern Media in Oppression

Furthermore, Griffin claims that Southern newspapers played a role in further perpetuating the cycle of oppression and antiblack stereotypes. These papers typically published stories about Black Southerners engaged in negative behaviors (such as sexual assault) and they usually failed to publish stories about Black Southerners’ positive behaviors (such as educational accomplishments). Additionally, Southern newspapers typically neglected to report instances of racism. These biased portrayals gave white readers the false impression that Black people were more hypersexual, criminal, and unintelligent than white people.

(Shortform note: Recently, several newspapers have apologized for the role they’ve played in perpetuating racist ideas (such as stereotypes) in the past. For instance, The Baltimore Sun published an editorial in which they apologized for the publication’s racist coverage of news events over the past 185 years. Their editorial addresses several of the issues Griffin raised about Southern newspapers: They apologize for publishing disproportionately more stories about Black crime than Black achievement, as well as emphasizing the views of police over those of Black people claiming that police targeted them. While some claim that such apologies are coming too late, others praise these papers for their efforts to make amends.)

Racial Progress Is Possible

Although Griffin emphasizes the challenges, like the cycle of oppression, that hinder racial progress, he also claims that racial progress is possible. His time in Atlanta, Georgia reassured him that there was hope for Black Southerners in other cities if they followed Atlanta’s example. In this section, we’ll explore four of Griffin’s insights about hope for racial progress in the South.

Insight 1: Black Unity Was Possible

First, Griffin’s conversations with Atlanta’s leaders and citizens led him to conclude that Black people could build economic power through collaboration. For instance, several Black leaders in Atlanta pooled the community’s funds so Black residents could take out loans to buy homes.

(Shortform note: Recent data reveals that Black Atlantans are still fighting to build economic power through homeownership. Today, Black Atlantans are underrepresented in the city’s mortgage market. In a list of U.S. cities with the lowest rates of Black homeownership, Atlanta ranks number seven. According to experts, income inequality in Atlanta may explain this gap: Black residents’ median household incomes lag nearly $20,000 behind the city’s median household income. The Community Foundation for Greater Atlanta recently formed a coalition to work with the city and its nonprofits to reduce the city’s racial homeownership gap.)

Insight 2: Black Colleges and Universities Improved the City

Second, Griffin contends that Black colleges and universities in Atlanta positively impacted the city’s Black community. These institutions, such as Morehouse College and Spelman College, encouraged their students to grapple with the cycle of oppression so they graduated well-equipped to fight it. Additionally, these institutions emphasized students’ responsibility to give back to their local communities after graduating.

(Shortform note: Today, HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in Atlanta claim that they continue to push their students to learn about racial justice. Morehouse and Spelman Colleges teach their students critical race theory, an examination of how ideas of race shape culture and policies. For instance, Spelman offers courses in the psychology of racism and engages students in research on reparations for slavery.)

Insight 3: An Honest Press Promoted Racial Equality

Third, Griffin claims that Atlanta’s city newspaper, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, honestly shared stories on racial inequality. According to Griffin, it promoted antiracist views under the leadership of its editor, Ralph McGill. This set it apart from many other newspapers in the South that published prejudiced stories about Black people and received funding from racist organizations.

(Shortform note: Historians support Griffin’s view that under the leadership of Ralph McGill, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC) was a source of news that supported the civil rights movement. However, Griffin doesn’t acknowledge that prior to McGill serving as editor, the newspaper spread racist ideas. McGill’s views on racism contrasted with those of Henry Grady, who in the 1880s edited The Atlanta Constitution (which was later part of a merger that resulted in the AJC). In Stamped From the Beginning, Ibram X. Kendi credits Grady with creating the idea of “separate but equal”—a doctrine that promoted racial segregation. Kendi argues that this idea paved the way for future racist policies.)

Insight 4: Atlanta’s Leaders Advocated for Black Rights

Finally, Griffin argues that many of Atlanta’s leaders supported policies that advanced Black lives. Some of these leaders were white: For example, Atlanta’s mayor, William Hartsfield, backed policies that supported racial equality. Many of Atlanta’s other leaders were Black business owners and civic leaders who involved themselves in politics so they could advocate for antiracism at the state and national levels. For instance, Democratic attorney A.T. Walden and Republican civic leader John Wesley Dobbs formed the Atlanta Negro Voters League, a bipartisan group that elected city and county leaders who supported racial justice.

| Support for Anti-Racist Policies in Atlanta Griffin emphasizes the fact that these leaders stood for racial progress because they supported antiracist policies. In How to Be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi agrees that the key to ending racism is enacting antiracist policies. According to Kendi, antiracist policies are laws, rules, and processes that create or sustain racial equity. Although Griffin names several Atlanta leaders who supported antiracist policies, he doesn’t describe their specific policies. Let’s examine several of the antiracist policies these leaders supported during the civil rights movement: – A.T. Walden played a role in ensuring that black teachers in Atlanta earned the same amount as their white colleagues. – John Wesley Dobbs organized an effort to hire eight Black policemen for Atlanta’s police force. – Mayor Hartsfield supported the legal desegregation of Atlanta’s businesses when he ensured that charges were dropped against Martin Luther King Jr. and the students who participated in a sit-in that protested segregated restaurants. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of John Howard Griffin's "Black Like Me" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Black Like Me summary:

- The 1959 story of a white man who spent six weeks living as a Black man

- The brutal racism Black southerners faced in the mid-1900s

- Griffin’s insights about hope for racial progress in the South