How can you keep your readers from missing your message? How can you get nearly anyone interested in an essay about prairie grasses?

Whether you’re writing an email or a novel, you want to compel your readers and get your message across. The following writers’ exercises will help you achieve unity in your writing, infuse your writing with humanity, find your own Paris (inspired by Ernest Hemingway), and practice using the pyramid structure.

Continue reading to dive into these exercises and strengthen your writing.

Writers’ Exercises

We’ve put together four writers’ exercises based on the concepts in books by William Zinsser, Ernest Hemingway, and Barbara Minto. These are exercises you can return to time and time again to improve your writing skills.

Exercise 1: Achieve Unity in Your Writing

In On Writing Well, William Zinsser discusses the concept of unity, which you achieve when certain key elements stay the same throughout your writing, even as your idea develops. For example, tone is one key element to keep consistent in a piece of writing. Zinsser believes unity eliminates unwanted confusion because your reader won’t have to keep up with unnecessary changes in your writing.

Zinsser explains that, while you can take some artistic liberty with your writing, you have to stick with whatever decisions you make. As you write, you can change your mind, but make sure that change is reflected throughout the rest of your writing. For example, you may start writing a piece in third person, only to decide midway through that you think first person would work better. It’s okay to change your mind, but be sure to go back and change the parts you’ve already written in third person to first person.

Zinsser says that, to achieve unity in your writing, you should answer four guiding questions about your main idea, point of view, tense, and tone.

- Think of your current writing project. It could be an essay, travel guide, or letter—any kind of writing. What’s the main idea of this piece of writing? What’s the one thing you want your reader to take away from your writing?

- How will you address the reader? What point of view is most appropriate for this piece of writing, and why?

- What tense will you use? Why will this work best?

- What tone will you use? What is your attitude—as the writer—to the piece? For example, if you’re writing an article about a political protest, your tone might be more serious than if you wrote a more conversational review of a new movie.

Exercise 2: Infuse Your Writing With Humanity

For unique and engaging writing, Zinsser believes that you must find humanity, or the part of your writing that your reader will connect with. Humanity speaks to some shared experience or deeper truth about being human. For example, in Educated, Tara Westover speaks to the experience of overcoming family limitations and the importance of education. These are deeper truths a reader can relate to, even if he didn’t grow up in a survivalist Mormon family.

Zinsser believes humanity is why we read stories about niche topics such as fly-fishing or rock climbing. It’s not because we all have a specific interest or knowledge of these things but because we can relate to the people who do have a passion or interest in something. We resonate with someone’s resilience through hardship or search for meaning because most of us have had similar experiences.

Consider what deeper truth your story speaks to. Incorporating humanity, or some truth about being human, will make your writing more engaging. In this writers’ exercise, identify some underlying truths in your writing so you can craft more compelling stories in the future.

- Think of a story you’re currently writing, would like to write, or wrote in the past. What was the story about? Give a brief description of the piece.

- Now dig a little deeper. What was your writing really about? What kind of truth did it speak to? Perhaps your company memo was really about the desire to improve your sales performance or your profile on a local baker was about the preservation of family values and customs.

- Finally, think about what truths you value most, such as family or loyalty. If nothing immediately comes to mind, consider what kind of stories you gravitate toward. Maybe you like murder mysteries and the search for justice or knowledge, or maybe you like biographies of entrepreneurs and their ability to overcome obstacles and solve important problems. Describe what truths you’d enjoy exploring.

Exercise 3: Find Your Own Paris

Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast is a collection of vignettes about his time in Paris between 1921 and 1926. He tells the story of his interactions with some of the most famous artists of his generation. Amid vivid descriptions of going hungry and walking the streets of a city in flux during the interwar period, Hemingway describes literary greats like Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and others who influenced his development as a writer.

Paris seemed bleak when the winter rains came, and the small shops selling newspapers or herbs closed their doors. Hemingway lived in the hotel where French poet Paul Verlaine died, and it got cold in his apartment, which was somewhere between six and eight stories up, when the rains began. Hemingway often walked around the city, down the Boulevard St.-Michel and the Boulevard St.-Germain, past the Cluny Museum, and found a café on the Place St.-Michel where he would write. When the rains dissipated and the weather turned cold and clear, Paris became a different, more energized city. The bare trees in the Luxembourg Garden looked like sculptures. Even the stairs up to his apartment in the hotel didn’t feel so bothersome.

In this writers’ exercise, think about an important place in your own life in the same way Hemingway thought about Paris.

- If you are older than 25, remember where you spent your early 20s. If you are younger than 25, think about your childhood. If you were writing a memoir, what places would you be sure to include? Why?

- What events would you need to include to paint a detailed picture of this time in your life? Why would you need to include them?

Exercise 4: Use the Pyramid Structure

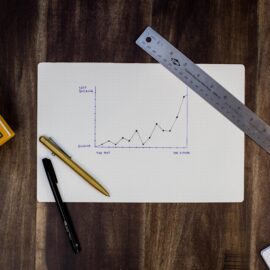

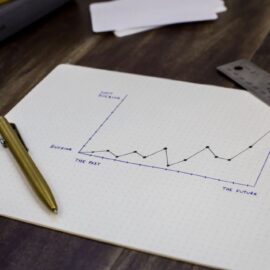

In The Pyramid Principle, writing expert Barbara Minto argues that the secret to clear, effective prose writing is beginning with your conclusions. She envisions strong writing to be structured like a pyramid, with conclusions at the peak and supporting evidence branching out beneath. Minto claims that strong writers brainstorm and organize their ideas into a pyramid structure before they begin writing.

Practice this now with this writers’ exercise. Pick something to write, brainstorm your conclusions and supporting ideas, and draft your introduction.

- Think about something you plan to write. It could be informative (such as a report summarizing your company’s progress), expressive (such as a thank-you letter to a friend), or persuasive (such as a message persuading your social media followers to contribute to a fundraiser). Then, describe your writing piece’s topic, question, and answer (or Peak Conclusion). (For example, your topic may be an upcoming fundraising effort for hurricane relief victims. A reader may wonder, “Why should I donate?” Your answer may be that their donation will save lives and restore victims’ hope.)

- Now, use Minto’s top-down approach to generate ideas that support your Peak Conclusion. Start by imagining what question a skeptical reader would ask in response to your answer (your Peak Conclusion). Then, write your Tier 1 conclusions. (For instance, a skeptical reader may wonder, “How will my donation save lives and restore hope?” This could lead you to generate the following two conclusions: “Your donation will provide hurricane victims with emergency supplies such as medicine, food, and water” and “Your donation will provide hurricane victims with hope and reassurance that their community is here to support them.”)

- Continue using this question-and-answer technique to generate your next row of supporting ideas. (For instance, a reader might wonder how their donation will provide medicine, food, and water to hurricane victims. You could explain which organizations will be using their donation and what type of relief each organization will provide for families.)

- Finally, draft an introduction that includes a beginning (which establishes the “where” and “when” of your topic), a middle (which raises the question or problem), and an end (which shares your Peak Conclusion and Tier 1 conclusions). (For example: “A local charity is raising funds to support hurricane survivors. Why should you donate? Because doing so will provide hope to those who’ve suffered great loss and save lives by providing food and water.”)