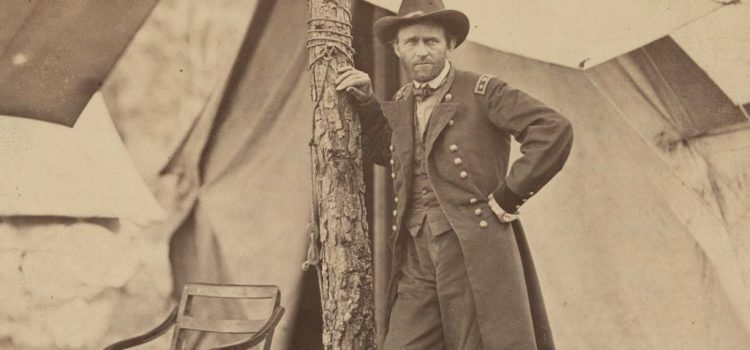

What was it like to follow Ulysses S. Grant in the Civil War? What kind of leader was Grant?

In 1862, Grant was promoted to Major General of Volunteers, making him the second-highest general in the Western Theater. Contrary to Grant’s critics, author Ron Chernow argues that Grant was a cunning strategist and leader in the Civil War, both on and off the battlefield.

We’ll focus on two key examples of Grant’s leadership in the Civil War: the Vicksburg campaign and his post-victory treatment of Confederates.

Grant’s Cunning in the Vicksburg Campaign

Chernow’s book Grant contends that the crucial victory in Vicksburg, Mississippi by Ulysses S. Grant in the Civil War, along with the various preceding battles that constitute his “Vicksburg campaign,” showed that Grant was capable of outwitting and outmaneuvering his opponents, propelling him to victory while also losing fewer troops.

For further context, Chernow points out that Vicksburg was strategically vital to the Confederacy as the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River—the key means of distributing goods to Confederate armies. He notes that, as Grant’s 43,000 men marched south toward Vicksburg, they won five battles against a total of 60,000 Confederate soldiers. Yet, while the Confederates suffered 7,200 casualties, Grant suffered only 4,300—a counterpoint to the narrative that Grant rashly sacrificed troops and won battles by overwhelming numbers alone.

(Shortform note: Though Grant deserves praise for sacrificing fewer men than the Confederates during his Vicksburg campaign, he suffered outsized losses in other battles. For example, in the Battle of the Wilderness, in which Grant began his offensive against Richmond, the Confederate capital, the Union suffered many more casualties than the Confederates—17,500 compared to about 13,000.)

Then, after several failed assaults on Vicksburg, Grant instead decided to lay siege to Vicksburg, meaning that he surrounded the fortress to prevent Confederate troops from receiving food, water, or reinforcements. Chernow argues that, because Vicksburg was well-fortified, this was a prudent strategic move; by engaging Vicksburg in a war of attrition, Grant avoided unnecessarily sacrificing troops through continued frontal assaults. Moreover, Grant successfully seized the high ground—Haynes’ Bluff—which left the Confederates with little hope of successfully escaping.

(Shortform note: While Grant’s particular decision to lay siege to Vicksburg helped minimize combat-related casualties, sieges often have several disadvantages that make them an unappealing option. In The Art of War, Chinese philosopher and warrior Sun Tzu argues that sieges should only be a last resort because they require months worth of resources that prove extremely costly. In practice, long-lasting sieges can frustrate commanders, causing them to launch frontal assaults that often result in severe casualties.)

As Chernow relates, Grant’s strategic cunning was rewarded on July 4, 1863, as Confederate General John Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to the Union; with dwindling rations, the war of attrition left Pemberton no choice but to surrender.

(Shortform note: Relative to the Confederates, Grant’s casualty rate was better during the siege of Vicksburg than it was in the battles leading up to Vicksburg—experts report that Union troops only suffered about 5,000 casualties, compared to over 32,000 casualties for the Confederates.)

The Magnanimous Victor

According to Chernow, Grant’s strategic genius extended beyond the battlefield. Specifically, Chernow argues that through his magnanimous treatment of defeated Confederate soldiers, Grant displayed a long-term understanding of how to minimize casualties and conciliate the South.

For example, Chernow points out that after the Vicksburg campaign, it was initially tempting for Grant to treat captured Confederates cruelly—as traitors against the Union, harsh retribution seemed a natural response. Yet, he notes that Grant did the opposite: He offered to allow Confederate soldiers to retain traditional war honors and parole them rather than taking them captive. Chernow suggests that, in so doing, Grant practically ensured Confederates accepted his offer of surrender, thus avoiding gratuitous bloodshed.

In a similar vein, Chernow contends that Grant’s treatment of Confederates following their 1865 defeat at Appomattox—in which Grant defeated Southern General Robert E. Lee, marking the beginning of the end of the Civil War—showcased Grant’s understanding of the long-term strategy needed to reunify the nation. Once more, Grant offered Confederate troops parole rather than doling out retributive punishment, even providing food rations for the dilapidated Confederate army. According to Chernow, this magnanimous act won Grant the gratitude of the South and drastically improved the prospects for post-war reconciliation.

| Is It Rational to be a Magnanimous Victor? Although Chernow finds Grant’s magnanimous treatment of Confederates praiseworthy, scholars note that it’s often unclear whether magnanimity toward our enemies is rational. For example, political scientists Steven Brams and Ben Mor point out that while magnanimity can assuage our enemies’ desire for revenge, it can also help opponents recover and thereby enable their revenge in the future. According to Brams and Mor, either response can be rational under certain circumstances. They argue that a magnanimous response is rational whenever the defeated opponents might attempt to rebel if the victors doled out harsh punishment. For example, if Grant believed that Lee’s Confederates would lash out under harsher terms of surrender, it would be rational for Grant to be magnanimous. By contrast, Brams and Mor argue that a non-magnanimous response is rational whenever the defeated opponents would not rebel if the victors doled out harsh punishment. After all, harsh punishment has no downside for victors in such circumstances—it leaves the defeated enemy less capable of reestablishing itself down the line and runs no risk of rebellion in the short-term. In Grant’s case, Chernow implies that Confederates likely would have rebelled against harsher terms both at Vicksburg and Appomattox, meaning Grant’s decision to treat defeated Confederates charitably was rational. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ron Chernow's "Grant" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Grant summary:

- A biography of Ulysses S. Grant that paints him in a new light

- Grant's role in the Civil War and as president of the United States

- How Grant fought valiantly against alcohol addiction