This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Skin in the Game" by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are the two types of inequality? How does the free market help reduce economic disparity between classes?

According to Nassim Taleb, there are two types of wealth and two types of inequality: static and dynamic. Static inequality refers to the wealth disparity of a population at any given single point in time. On the other hand, dynamic inequality refers to the inability of a given individual to rise in economic class across a lifetime.

In this article, we’ll explore the difference between Taleb’s two types of inequality. Then, we’ll examine Taleb’s argument that the free market does the most to reduce economic inequality.

Good Wealth and Bad Wealth

Taleb uses the concept of skin in the game to distinguish between two categories of wealthy people: those who built and maintain their wealth through skin in the game, and those who built and maintain their wealth with minimal-to-no risk. Taleb argues that we want more of this first type of wealth and less of the second.

First, let’s discuss wealthy people with skin in the game. These are people who earned money through risky ventures and sacrifice—entrepreneurs, artists, anyone who habitually took risks that eventually paid off. Alternatively, these could be people born into money—kings, heirs—who risked their fortunes, reinvested, and were able to create more wealth.

Importantly, Taleb notes that wealth is not necessarily a zero-sum game. If wealth is correctly invested, it can create more wealth than would have otherwise existed, and distribute some of that wealth to others. Think of Adobe, for example, a company that creates industry-grade creative software (Photoshop, After Effects). By investing wealth in the risky prospect of creating software that people might not want to buy, Adobe enabled millions of its users to create value (appealing graphics, movies with special effects) and earn wealth for themselves (a paycheck for creative work). This new wealth wouldn’t exist without Adobe, and wouldn’t have existed without the wealth of its initial investors. In this way, wealthy people with skin in the game generally use their wealth in ways that better society.

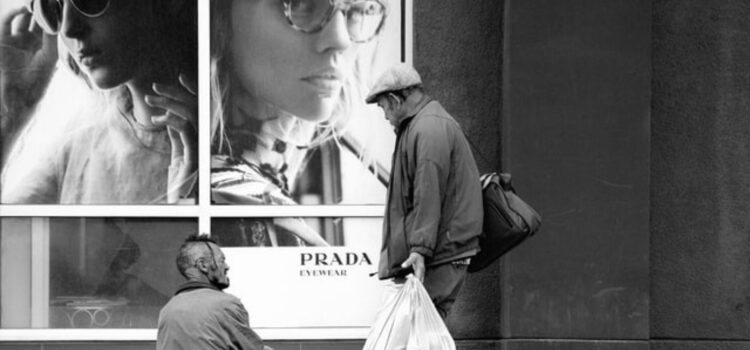

This group of wealthy people isn’t necessarily resented by those poorer than them—on the contrary, they are often admired, and perceived as skilled and hardworking. Beloved actors, famous authors, and bootstrap entrepreneurs are often rich—sometimes outrageously rich—yet they attract adoring audiences. Many would say these people “deserve” their wealth.

In contrast, let’s take a look at wealthy people without skin in the game. These are people who created wealth in ways that don’t contribute value to society—often by taking advantage of others. This group consists of anyone whose income is independent of the value of their work, and as such, is being earned without risk.

Taleb specifically calls out employees in salaried positions that don’t provide value for others, such as predatory gossip bloggers, dishonest lawyers, ineffective government bureaucrats, or corrupt CEOs. Recall that employees are paid for fulfilling job descriptions, and that their work is not necessarily linked to its consequences. A guaranteed salary removes a degree of skin in the game, allowing this second group of people to amass wealth without risking much or generating real value. Taleb states that this second group of people are more resented by the general public, and rightfully so.

These two opposing types of wealth are vital to understanding economic inequality—one kind of wealth is relatively healthy for society, while the other is not.

The 2 Types of Inequality

In view of these two categories of Good Wealth and Bad Wealth, Taleb distinguishes between two types of inequality: “Static” Inequality and “Dynamic” Inequality.

Static inequality is the inequality of a population at a point in time. Dynamic equality can be understood as two-way income mobility—how easy it is to earn more wealth, as well as how easy it is to lose the wealth you have. A perfectly Dynamically Equal society would be one in which no individual spends more time in any one income bracket than anyone else. In other words, dynamic equality is skin in the game of wealth—your financial status is always at risk.

Why Is Dynamic Equality Better Than Static Equality?

Taleb implies that a perfectly Dynamically Equal society would be better off than a perfectly Statically Equal society.

An ideal society is one in which everyone, rich and poor, has skin in the game. If you do good for others, you should be rewarded. If you harm others, you should be punished. This is the definition of skin in the game and the foundation of a healthy society. An ideal market should reward wealthy people who invest their wealth in risky ventures that benefit others. Those who do not should eventually lose their wealth.

Dynamic equality allows those who create value to become richer, while forcing those who don’t to become poorer. For this reason, dynamic inequality is a far more important statistic to measure than static inequality—it measures how well a society rewards those who contribute to the collective and punishes those who do not. It measures skin in the game.

Judgments made based on measurements of static inequality can result in faulty conclusions. Even if you chart the data of static inequality across time, it’s impossible to tell how the income of specific people is changing.

For example, if you’re looking at static inequality, Europe appears to be more egalitarian than the United States—their wealth is more evenly distributed across the population. But Taleb uses some statistics of dynamic inequality that propose America may be fairer than Europe. In Europe, more than a third of the five hundred wealthiest people inherited their wealth from family dynasties that have lasted for centuries. Compare this to the US, where 90% of the wealthiest five hundred people entered that list less than thirty years ago.

Here’s another statistic on dynamic equality in America: 10% of Americans will spend at least one year in the top 1% of income earners, and more than half of all Americans will spend at least a year in the top 10% of income earners. Since what we’re trying to do is allow the market to reward those who contribute to society, greater turnover among the rich in the United States is a sign of fairness.

In Taleb’s opinion, dynamic inequality is something to resent far more than static inequality. In our uncertain world, the only way an individual permanently stays in a high income bracket is if he doesn’t have skin in the game. In this way, dynamic inequality indicates wealth that is unfairly exempt from risk, failing to contribute value to society.

The Free Market Increases Dynamic Equality

Taleb argues that the way to reduce dynamic inequality is to force those with wealth to risk it in order to avoid losing it. In short, to put their skin in the game. For the most part, the free market does this automatically.

Free markets are “Winner-takes-all” in regards to wealth. If a company can offer a significantly higher quality product than its competitors, it receives a dominant market share. For example, when DVDs were invented, VHSs soon became completely extinct. A winning company could stop being a winner at any time, meaning that those collecting its profits are always at risk. The company continues earning only as long as it’s generating more value for society than its competitors.

Why the Upper Class Pushes for Static Equality

Taleb asserts that the intellectual upper class is far more invested in the fight for economic equality than the lower class they claim to be fighting for. To this point, he cites the book The Dignity of Working Men by Harvard professor Michéle Lamont. In it, Lamont extensively interviews low-income workers and discovers that generally, they don’t harbor the same resentment toward the super-rich that the upper class does.

To explain why, Taleb puts forward the principle that people generally envy those close to them, in proximity and social class. Since salaried academics are closer in status to the über-rich, they’re more likely to compare themselves to them. They’re jealous, and deem the concentrated wealth of the richest people to be unfair.

Despite the fact that economics and other academics have no skin in the game of inequality, they assume they know what is best for the lower class and want to dictate economic policy for them. Upper-class intellectuals won’t be the ones to face the consequences if their theories harm the lower class, so Taleb argues that they shouldn’t be involved.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's "Skin in the Game" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Skin in the Game summary :

- Why having a vested interest is the single most important contributor to human progress

- How some institutions and industries were completely ruined by not being invested

- Why it's unethical for you to not have skin in the game