This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Mythologies" by Roland Barthes. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s a myth? How is a myth made and used? Are myths dangerous?

According to 20th-century French philosopher Roland Barthes, myth is all around us. In Mythologies, he discusses the process of mythmaking. He identifies the basic components of myth and explains what function they have in society. He also warns that myths can pose certain dangers.

Continue reading to understand Barthes’s take on myth.

Roland Barthes on Myth

Before discussing how myth appears in society, let’s first define myth as Barthes presents it. According to Barthes, myth is a message that’s conveyed when an object, image, or phrase becomes associated with a concept or value, and thus takes on a symbolic meaning. For example, a national flag may be associated with the concept of freedom, conveying a message about that nation to its citizens. Myths shape the way we view the world and hold power over us when society’s dominant institutions—for example, the government, the advertising industry, or Hollywood—craft these messages for us.

| The Use of Imagery to Reinforce Power Structures In his 1972 book, Ways of Seeing, art critic John Berger discusses the ways that art can be used to influence public perceptions and understandings of the world. He refers to this manipulation of the public by the powerful as mystification, a term drawn from Marxist rhetoric. In Marx’s view, the ruling class intentionally mystified the concept of capitalism by creating mythologies around the merit of hard work and free enterprise and obscuring the realities of the vast economic and power inequities it created. Similarly, Berger says throughout Western history, art has been associated with the wealthy elite, who have used it to promote specific perspectives and obscure others, in order to reinforce class distinctions. Berger includes a discussion of the use of advertising imagery in service of capitalism, which we will see is a focus of Barthes’s as well. |

The Components of Myth

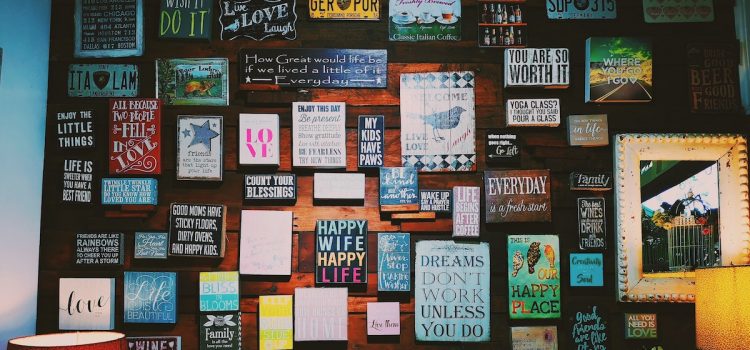

Barthes argues that myths have two basic, interrelated components: a form and a concept. The form of a myth is concrete: It is the actual object, image, or phrase that we perceive with our senses. Anything can become the form, or raw material, of a myth—it could be a song, a photo, or an everyday object such as a car or an article of clothing.

Barthes explains that, on their own, these materials have a literal meaning. When we see a car, we recognize it as a vehicle of transportation. When we listen to a song, we understand its words. However, the power of myth is that it imbues these things with additional meaning. Myth occurs when society connects the raw material of form to an abstract concept.

Barthes suggests also that myth doesn’t just add new meaning to the raw material—it also distorts the original meaning. According to Barthes, this receding of the form’s meaning is important because it allows myth to appear perfectly natural.

The Creation and Function of Myth

Now that we understand what Barthes means by myth, we’ll turn to a discussion of how myths are created and utilized in society. It’s important to recognize this because myths are being employed every day to influence our thoughts and perceptions of the world. According to Barthes, myth is essentially a means of culture creation. But, more specifically, he argues that it’s the creation of an “ideal culture” that obscures reality and diversity. And, particularly in the examples he analyzes, from 1950s France, he says myth is created by the “bourgeois” (upper-middle class) for the “petit bourgeois” (lower-middle class) and “proletariat” (working class). So, although Barthes doesn’t use the word, he’s essentially arguing that myth is propaganda.

He suggests that institutions in society (for example, the government, the fashion and advertising industries, and the media) create associations between certain signs and concepts, and the general population internalizes these associations and comes to see them as natural.

Barthes specifically aims to critique the class constructs that underlie the myth in his own culture (1950s France). He says myth is like a mask that presents a falsehood and shields people from harsh realities, which serves to sustain the social order and reinforce class distinctions.

The Dangers of Myth

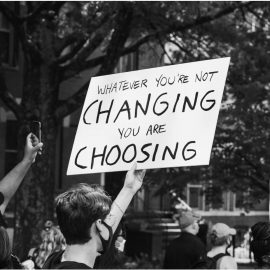

Barthes suggests that a defining characteristic of myth is its ability to appear as “natural” even though it is constructed. This means that people don’t question the myth and instead accept it as fact. When society’s dominant institutions utilize mythology to influence the population’s thoughts, this can serve to perpetuate and reinforce social inequalities. In this way, by not questioning the mythology around us, we participate in our own subjugation.

(Shortform note: For example, sociologists and psychologists analyze the ways that women participate in their own oppression by supporting the norms and values associated with patriarchy. This often comes in the form of “benevolent sexism”—that is, the belief that women need to be protected and cared for by men. By adopting this belief, women relegate themselves to a lower-status position in the social hierarchy.)

Barthes argues that myth is both necessary and problematic. It’s necessary to some degree, he says, because it creates a simplified and comfortable world for people in the face of harsh realities. For example, he discusses magazine advertisements for cleaning products as promoting an idea of cleanliness and purity that’s comforting and aspirational to people, while disguising the dirt and drudgery of domestic life. These ads typically depict a happy homemaker in a spotless, beautiful home—the reality women aspire to—while never revealing the hard work and sacrifice of caring for a home and children—the reality women actually live.

This example may seem relatively harmless, but Barthes points out that, when myth disguises the “dirt” of more serious issues like racism, sexism, or fascism, then we enter into dangerous territory, where people can come to accept these as natural and normal and fail to challenge them.

According to Barthes, myths are everywhere in our society, and most people go through their day without recognizing them for what they are. Myth always has a motivation, however, and Barthes says it’s the perfect vehicle for promoting political agendas. This has the dangerous implication that people can be manipulated into supporting social and political agendas that go against their own interests or values and uphold oppressive social structures.

| The Mythology of the MAGA Hat An example of mythmaking from recent US politics is Donald Trump’s use of the red baseball cap, which includes his campaign slogan “Make America Great Again.” This is arguably one of the most iconic and powerful symbols in American political history. There are multiple layers of myth here. The slogan itself is an example of a myth designed to appeal to a nostalgia-based conservative political agenda. This myth is layered with the recognizable object, the baseball cap, an item most strongly associated with the American rural working class—a demographic that Trump courted aggressively. Since Trump’s presidency, the red baseball cap in America has taken on a whole new meaning, symbolizing not only support for Trump but many other assumptions about the wearer’s political beliefs and identity. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Roland Barthes's "Mythologies" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Mythologies summary:

- The subtle messages that subconsciously shape the way we view the world

- How myths are used to reinforce cultural norms and values

- Why myths can pose dangers to society