Most people don’t handle uncertainty well—we rely on gut feelings and vague language like “probably” or “likely” that mean different things to different people. The Art of Uncertainty by David Spiegelhalter reveals why our intuitions about uncertainty mislead us and offers a better approach: probabilistic thinking.

If you master Spiegelhalter’s method for dealing with uncertainty, you’ll make better predictions, communicate risks clearly, and avoid both overconfidence and excessive caution. In our overview, you’ll learn why most “coincidences” are statistically inevitable, how to update beliefs when facing new evidence, and why intellectual humility beats false certainty.

Overview of The Art of Uncertainty

Uncertainty surrounds us—from trivial guesses about tomorrow’s weather to high-stakes decisions about medical treatments, business investments, and global risks. Yet most people handle uncertainty poorly, leading to catastrophic failures in judgment. The Art of Uncertainty by David Spiegelhalter argues that we struggle with uncertainty because we rely on intuition and vague language to reckon with what we’re not sure about rather than employing systematic reasoning and numbers.

As Emeritus Professor of Statistics at Cambridge University and former Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk, Spiegelhalter has spent decades studying how people interpret and communicate uncertainty. His central insight is that uncertainty is fundamentally subjective—a relationship between an observer and the world rather than a property of the world itself. This explains why different people can legitimately hold different degrees of uncertainty about the same event and why probability represents personal judgment rather than objective fact. When we recognize this, we can use probability as a tool for quantifying our uncertainty, learning from evidence, and making better decisions.

This guide unpacks Spiegelhalter’s ideas in three parts: why humans are naturally poor at handling uncertainty, how probability provides better tools for thinking about it, and how you can navigate uncertainty in real-life decisions. Throughout, we also explore how philosophical debates about probability’s nature affect scientific practice, examine why cognitive biases undermine even sophisticated statistical reasoning, and provide tools for improving how you think about uncertainty.

What Is Uncertainty, and Why Are We Bad at Understanding It?

Humans evolved to make quick decisions so we can avoid threats and take advantage of opportunities. Spiegelhalter explains that while this served our ancestors well, it leaves us poorly equipped to handle modern-day uncertainty, such as making medical decisions, evaluating financial risks, or understanding scientific claims. In this section, we’ll examine what uncertainty is and why it varies from person to person. Then we’ll explore how our intuitions lead us to misjudge randomness, misinterpret coincidences, and confuse luck with skill.

Uncertainty Is Personal and Subjective

Spiegelhalter defines uncertainty as a relationship between an observer and the external world rather than a property of the world itself. Put simply, this means that uncertainty depends on what the observer knows or doesn’t know.

Consider an example: Your friend flips a coin, peeks at the result, sees that the coin landed on tails, but doesn’t show it to you yet. Before the flip, you both would say there’s a 50% chance the coin will land on heads. After the flip, but before you see the result, you’d still say there was a 50% chance because nothing has changed from your perspective. But your friend knows with full certainty that there’s a 0% chance it landed on heads. You’re both considering the same coin at the same moment in time, but you have different levels of uncertainty because of what you know.

Spiegelhalter distinguishes between two types of uncertainty. Aleatory uncertainty emerges from genuine unpredictability—the randomness in rolling dice, flipping coins, or trying to predict the exact path of a hurricane. No amount of additional information can eliminate this uncertainty because the events themselves are random. Epistemic uncertainty, by contrast, emerges from your lack of knowledge about things that have definite answers, like your uncertainty about your grade on a final exam after the test has been scored but before your grade has been posted.. Epistemic uncertainty can often be reduced by gathering more information.

In addition to distinction between aleatory and epistemic uncertainty, Spiegelhalter identifies different levels of uncertainty. Direct uncertainty concerns the outcome itself, such as when you’re uncertain whether a particular decision will turn out well. Indirect uncertainty concerns the quality of your analysis and the strength of your evidence. You might assess a 70% probability of success (direct uncertainty), but have low confidence in that assessment because your information is limited or your assumptions are questionable (indirect uncertainty). At the extreme is deep uncertainty, where you can’t even list the possible outcomes because you’re uncertain about what scenarios are even possible, not just about which scenario will unfold.

Our Intuitions About Uncertainty Fail Us

Evolution equipped us with powerful pattern-recognition abilities and quick decision-making instincts—cognitive shortcuts that allow us to make decisions quickly. Spiegelhalter reports that while these abilities can benefit us, they can produce systematic errors when they affect how we assess uncertainty.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman provides insight as to how this works: He describes human thinking as operating in two modes: System 1 (fast, instinctive, emotional) and System 2 (slow, deliberative, logical). System 1 tends to dominate, and it produces predictable mistakes: overconfidence, neglect of background information, undue influence from how questions are framed, excessive focus on rare but dramatic events, and suppression of doubt.

Spiegelhalter explains that the cognitive shortcuts of our System 1 thinking lead us astray in three specific ways. First, we expect random sequences to look more regular and evenly distributed than they are. If you flip a coin 20 times, you might expect something like: heads, tails, heads, tails, and so on, with a few short runs of heads or tails, but mostly conforming to an alternating pattern. Spiegelhalter notes that random sequences are much “clumpier,” and there’s a 78% probability of getting at least one run of four heads or tails in 20 flips. These clusters aren’t meaningful patterns, but the natural clumpiness of pure randomness feels non-random to human intuition.

Second, we underestimate the likelihood of surprising coincidences because they feel so improbable. Spiegelhalter cites the Law of Truly Large Numbers, which states that when you create enough opportunities, even very rare events inevitably occur. Consider the birthday problem: In a group of just 23 people, there’s better than a 50% chance that at least two people share a birthday. A group of 23 seems like an impossibly small number of people for such a high likelihood of a match, since there are 365 possible birthdays. But with 23 people, there are 253 different pairs, each presenting an opportunity for a shared birthday. With that many opportunities, even a low-probability match on any single pairing becomes likely overall.

This principle extends far beyond birthdays—with billions of people having countless experiences daily, spectacularly unlikely coincidences will happen to someone somewhere.

Third, says Spiegelhalter, we attribute random outcomes to skill or quality. When a book becomes a best seller, we credit the author’s talent, the marketing strategy, or its compelling story. When a book flops, we blame poor writing or bad timing. But luck plays a much larger role than most people recognize. Even publishing industry experts can’t reliably predict which books will succeed—manuscripts rejected by multiple publishers sometimes become massive hits, while books that publishers expected to succeed often fail. This doesn’t mean skill doesn’t matter, but that we overestimate how much control people have over their outcomes.

How Can Probability Help Us Think About Uncertainty?

Recognizing that our intuitions mislead us is the first step toward thinking more clearly about uncertainty. Spiegelhalter contends that the next step is adopting a better tool for talking and thinking about uncertainty: probability. In this section, we’ll examine what probability is and how it quantifies uncertainty. Then, we’ll explore why expressing uncertainty numerically beats using imprecise language, and what probability actually means philosophically. Finally, we’ll see how probability provides a method for revising what we believe as we learn new information.

What Is Probability?

Spiegelhalter explains that probability is a number between 0 and 1, often expressed as a percentage, that quantifies uncertainty. A probability of 0 means something is impossible, a probability of 1 means it’s certain, and a probability of 0.5 (50%) means it’s equally likely to happen or not. For instance, when statistician Nate Silver said there was a 28.6% probability of Donald Trump winning the 2016 US presidential election, he placed his uncertainty on this scale: closer to “won’t happen” (0%) than to “will happen” (100%), but not so close to zero that it’s negligible. This probability communicated both the direction of his expectation (Trump was more likely to lose than win) and the degree of his uncertainty (far from certain).

Probability provides mathematical rules for working with uncertainty. Spiegelhalter notes that the probability of two mutually exclusive outcomes must add up to 100%: If Trump had a 28.6% chance of winning, then Hillary Clinton had a 71.4% chance, because only one could have won. If you want to know the probability of two independent events both happening, you multiply their probabilities: If there’s a 70% chance of rain on Saturday and a 70% chance on Sunday, there’s a 49% chance (0.7 × 0.7) that it will rain on both days.

These rules don’t tell us what probability actually means—what it says about the world and our knowledge of it. But they do help us think about why expressing uncertainty numerically matters so much in practice.

Why Numbers Beat Words for Expressing Uncertainty

Spiegelhalter argues that numbers provide precision that words can’t. People express uncertainty using words like “likely,” “possible,” “probable,” or “rare,” but these mean different things to different people. Drug regulators call side effects that occur between 1% and 10% of the time “common,” but patients assume a “common” side effect is much more prevalent. However, when Silver assigned Trump a 28.6% probability of winning the 2016 election, this communicated something specific: In 100 similar situations, we’d expect that outcome roughly 29 times.

Spiegelhalter points out that expressing uncertainty numerically enables accountability over time. If Silver had said Trump’s victory was “unlikely” or “possible,” we couldn’t evaluate whether his judgment was well-calibrated. But because he’s provided numbers for hundreds of races over multiple election cycles, we can check: Do candidates he gives 70% odds win roughly 70% of the time? Do those he gives 30% odds win roughly 30% of the time? This reveals whether he’s overconfident (claiming more certainty than warranted), underconfident (hedging too much), or well-calibrated (his numbers match reality). With words like “likely” or “probably,” no such evaluation is possible because everyone interprets the terms differently.

What Probability Actually Means

Now that we understand probability as a numerical tool for quantifying uncertainty, a deeper question remains: What do these numbers actually represent? Do they describe something real about the world, or are they just useful fictions we construct? Spiegelhalter takes a philosophical stance that distinguishes his approach from standard statistics textbooks, but understanding his position requires examining what probability could mean according to different interpretations that have developed over time.

The Classical View: Probability Comes From Symmetry

Spiegelhalter explains that the classical view defines probability through physical symmetry: A coin toss has a 50% probability for heads because two equally likely outcomes exist and nothing favors one over the other. This view works for dice, coins, and cards, but it struggles elsewhere. What’s the probability of rain tomorrow? There’s no symmetry to appeal to, and calling outcomes “equally likely” presumes we know the probabilities.

The Frequentist View: Probability Is What Happens in Infinite Repetitions

The frequentist view, dominant in science, defines probability as the long-run proportion that would emerge if you could repeat the same situation indefinitely. Spiegelhalter explains that if we could flip a coin over and over without limit, the proportion landing on heads would approach 50%. This appeals to scientists because it’s based on observable frequencies. If a drug works for 70 out of 100 patients, we can estimate future probability from this frequency. But Spiegelhalter argues that this view faces serious limitations.

First, how do we apply this interpretation of probability to one-time events? An election will happen once: We can’t re-run it infinitely to see what proportion of times each candidate wins. The frequentist definition seems to suggest these one-time events don’t have meaningful probabilities at all. Second, even when repetition seems possible, deciding what counts as “the same situation” requires judgment. For instance, is every patient similar enough to those in clinical trials? Two patients are never identical—they differ in age, genetics, lifestyle, and countless other factors. Determining which differences matter and which can be ignored involves subjective decisions about what situations are “similar enough” to group together.

Spiegelhalter’s Subjective View: Probability Quantifies Personal Uncertainty

Spiegelhalter adopts a fundamentally different position: Probability represents a personal degree of belief based on an individual’s current knowledge and judgment, not objective features of the external world. When you say there’s a 60% chance of rain tomorrow, you’re not claiming to have measured some objective property of the weather system. You’re expressing your personal degree of certainty given what you know about weather patterns, forecast models, and atmospheric conditions. Someone with different information—perhaps a professional meteorologist with access to more detailed data—might reasonably assess the probability as 50% or 70%. Neither of you is objectively “right” or “wrong.”

The subjective view doesn’t deny that some probability assessments are better than others. It just recognizes that probability is a tool we use to organize our thinking about uncertainty, not a property of the world we can passively observe—probabilities represent judgments, not objective measurements made with instruments like thermometers or scales. Nevertheless, probabilities can still be evaluated for quality; they must connect to reality and can be tested against outcomes. If you consistently claim 60% confidence for events that occur only 30% of the time, your probability assessments are poorly calibrated.

This subjective interpretation has three practical implications:

First, probability applies meaningfully to one-time events. You can discuss the probability that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in assassinating President John F. Kennedy, or that Shakespeare wrote all the plays attributed to him, or that a particular company’s new product will succeed, because these probabilities measure your degree of certainty, not a repeatable likelihood.

Second, expert disagreement about probabilities doesn’t mean someone must be objectively wrong: Conflicting assessments can be legitimate quantifications of uncertainty from different perspectives.

Third, this view makes clear that all probability assessments involve judgment and interpretation, requiring honesty about the limits of our knowledge rather than false claims to objectivity.

Learning From Evidence: Bayesian Updating

If probability represents personal belief rather than objective fact, a question follows: How should our beliefs change when we encounter new evidence? This is where “Bayesian updating” enters Spiegelhalter’s framework. Named for 18th-century mathematician Thomas Bayes, Bayesian updating provides the mathematically correct way to revise subjective probabilities in light of new evidence. Bayes solved a fundamental problem: Given what you believed before (your prior probability) and given a new piece of evidence, what should you believe now (your posterior probability)? Bayes’ theorem shows how to combine your prior belief with new information to arrive at a logically consistent updated belief.

Bayes’ logic is straightforward: Your updated belief should reflect what you thought before and what the new evidence suggests. If you initially thought something was very unlikely but you then find a hint of evidence supporting it, you should increase your belief that it’s true, but only somewhat. Your prior belief matters because it captures everything you knew before new evidence arrived.

Spiegelhalter illustrates how Bayes’ theorem can play out in the real world with an example of a facial recognition system. Imagine that such a system scans a crowd of 10,000 people containing 10 suspects on a watchlist. The system correctly identifies 70% of the suspects and produces false alerts for only 1 in 1,000 innocent people (a 0.1% false alarm rate).

Now suppose the system flags someone. Should security detain them? Your intuition might be to focus on the system’s accuracy: a 70% correct identification rate with only 0.1% false alarms sounds reliable. But Bayesian reasoning reveals a different picture: The system would correctly identify 7 of the 10 suspects (70% of 10) and falsely flag 10 innocent people (0.1% of 9,990). In total, 17 people get flagged: 7 actual suspects and 10 innocent bystanders. Thus, if a person is flagged, there’s only a 7-in-17 chance—roughly 41%—that they’re on the watchlist. Despite the system’s impressive accuracy rates, the people it identifies are more likely to be innocent than guilty. Why does this happen?

The base rate—the rarity of what you’re looking for—matters enormously. Suspects make up only 0.1% of the crowd (10 out of 10,000). When you’re searching for something extremely rare, most of your alerts will be false alarms because there are many more opportunities for false positives than there are for true identifications. This is Bayesian reasoning in action: The prior probability (before being flagged) that any person in the crowd is a suspect was 0.1%. The new evidence (being flagged) updates this probability, since the system is more likely to flag suspects than innocent people. Bayes’ theorem quantifies how much to update: from a 0.1% to a 41% chance that someone is a suspect on a watchlist.

This increase from 0.1% to 41% seems substantial, but it’s less than most people intuitively expect when they hear that someone has been flagged by a highly accurate facial recognition system—many would assume the probability jumps to 80% or 90%. But, because the base rate was so low, it keeps the system’s level of certainty modest. This systematic approach to updating beliefs provides the foundation for thinking clearly about uncertainty.

How to Navigate Uncertainty in Practice

Having the right mathematical tools to quantify our uncertainty and update our predictions isn’t enough—we also need strategies to apply these tools in messy real-world situations where our models might be wrong and our knowledge is incomplete. In this section, we’ll explore Spiegelhalter’s practical principles for handling uncertainty when it matters most: distinguishing causation from correlation, communicating uncertainty honestly, understanding extreme events, and maintaining intellectual humility throughout.

1. Distinguish Correlation from Causation

One of the most common errors in reasoning about uncertainty is assuming that because two things occur together, one must cause the other. Spiegelhalter writes that establishing genuine causation requires far stronger evidence than mere correlation. Yet people, including researchers, routinely assume causal connections instead of looking for corroborative evidence from multiple sources.

For example, numerous studies show that teenagers who spend more time on social media report higher rates of depression and anxiety. Many have concluded that social media use causes mental health problems, driving calls for age restrictions and platform regulations. But does social media actually cause depression, or do depressed teens simply spend more time online? Or could a third factor—like having fewer in-person friendships—be causing both increased social media use and increased depression?

Establishing causation in this case is difficult because we can’t randomly assign teenagers to different levels of social media use for years—it would be unethical and impractical. Spiegelhalter says that randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for establishing causation because random assignment ensures that the groups in a study differ only by chance. Cross-sectional studies (such as looking at many teens at one point in time) can show correlation but can’t prove causation. Longitudinal studies (following the same teens over time) help determine whether social media use precedes depression symptoms, but can’t rule out confounding factors.

2. Admit Your Uncertainty

Prediction always involves uncertainty, but the degree of uncertainty varies depending on what you’re predicting and how far ahead you’re looking. Weather forecasting illustrates how this works. Meteorological models can predict the weather two days ahead quite accurately. Seven days ahead, their accuracy drops but remains useful. Beyond about 10 days, forecasts are much less useful because atmospheric conditions are chaotic, so meteorologists use ensemble forecasting, running multiple simulations with varied conditions. Spiegelhalter explains that you should match your approach to the time horizon and degree of certainty. It’s also crucial to be frank when uncertainty runs too deep to make reliable predictions.

Spiegelhalter argues that it’s crucial to be honest about your degree of certainty in your predictions. Many people assume that expressing uncertainty undermines credibility. Spiegelhalter argues the opposite: Transparency about uncertainty builds trust, while false certainty erodes it. It’s important to use numbers rather than words whenever possible, and to provide absolute risks alongside relative risks. The goal should always be to inform people about possibilities rather than to persuade them to see things your way, and to preempt misunderstandings by anticipating how people might misinterpret information.

3. Understand Extreme Events Without Overreacting

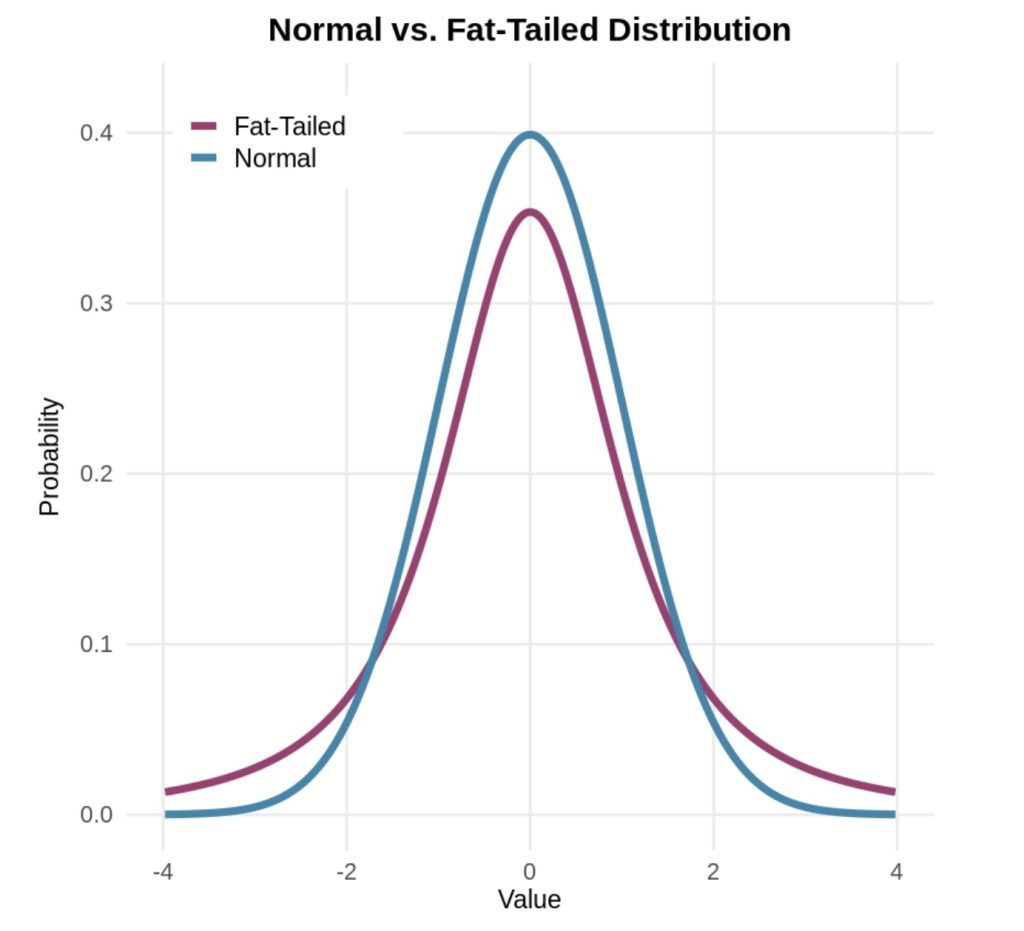

Our intuitions about extreme events mislead us because we expect data to cluster tightly around the average. Normal distributions (visualized with a classic bell curve) describe many phenomena—most values cluster near the average, with fewer and fewer appearing as you move toward the extremes. But financial markets, disasters, and pandemics follow fat-tailed distributions where extremes happen far more frequently. This explains why supposedly “one-in-a-million” events keep happening.

Spiegelhalter explains that understanding this helps us appropriately prepare for catastrophic events, so that we neither ignore the possibility that rare events will happen nor overreact when they occur. For example, after 9/11, the US implemented airport security measures requiring travelers to remove their shoes, limit liquids, and go through full-body scanners. These procedures cause massive delays, cost billions annually, and create stress for millions of travelers. Yet experts agree that TSA screening catches very few actual threats—and that the same resources would save more lives if directed toward other safety measures, like highway improvements.

4. Maintain Intellectual Humility

Finally, we need to exercise intellectual humility, acknowledging that our models are imperfect, our probability assessments are uncertain, and surprises will inevitably occur. Spiegelhalter advises to never assign exactly 0% or 100% probability to anything unless it’s logically impossible or certain. Always leave a small probability, even 1%, that your entire framework might be wrong. If you’re told two bags contain different colored balls and you draw balls to figure out which bag you have, you won’t discover if someone secretly filled both bags identically unless you assigned a small probability to the possibility that “my assumptions are wrong.”

The payoff of humility is adaptability. When you acknowledge uncertainty and stay open to the possibility that your understanding of the situation is wrong, you can update your beliefs quickly when reality diverges from expectations. Spiegelhalter sees humility as the foundation for learning from experience and making better judgments over time in an uncertain world.

FAQ

1. What is The Art of Uncertainty by David Spiegelhalter about?

The Art of Uncertainty explains why people struggle with uncertainty and shows how probability and clear reasoning can help us make better judgments and decisions in an uncertain world.

2. What is uncertainty?

Uncertainty is a relationship between an observer and the world, shaped by what a person knows or doesn’t know.

3. Why are humans bad at handling uncertainty?

We rely on intuition and mental shortcuts that evolved for quick decisions, which lead to predictable errors in modern situations.

4. What’s the difference between aleatory and epistemic uncertainty?

Aleatory uncertainty comes from genuine randomness, while epistemic uncertainty comes from lack of knowledge and can often be reduced.

5. How does probability help with uncertainty?

Probability puts uncertainty on a numerical scale, making beliefs clearer, more precise, and easier to evaluate over time.

6. Why are numbers better than words for expressing uncertainty?

Words like “likely” or “rare” are vague, while numbers communicate specific expectations and allow accountability.

7. What does Spiegelhalter mean by subjective probability?

Probability represents personal judgment based on current knowledge, not an objective feature of the world.

8. Why is intellectual humility important when dealing with uncertainty?

Admitting limits to our knowledge helps us stay open to new evidence and update our beliefs when reality surprises us.