This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Influence" by Robert B. Cialdini. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How do you react when you’re told you can’t have something? Do you accept it or do you want it more? What if someone tries to take away something you have? When your choices are limited you may experience psychological reactance.

Psychological reactance is the negative response you have when your choices are limited outside of your control. It comes from wanting to avoid loss.

See how your fear of losing options influences your decisions with examples including the Romeo and Juliet effect.

Why We Want What We Think We Can’t Have

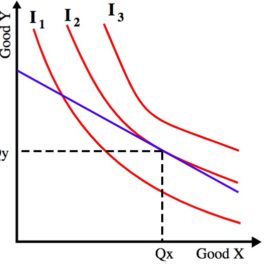

The Scarcity Principle tells us that we find more appealing those things with limited availability. On a basic level, we encounter this all the time: rare goods are expensive, while abundant items are cheap.

Scarcity, or the appearance of it, is a powerful motivating factor in influencing our behavior. We want things we can’t have—or at least think we won’t be able to have if we don’t act quickly and decisively.

Scarcity is closely related to the idea of loss aversion. As humans, we are powerfully guided by our desire to avert losing what we already have. We are inherently conservative and cautious. Loss aversion is a strong framing effect: we are more afraid of losing something than we are enticed by the hope of gaining something of equal value.

Maximizing Choices: The Magnetic Pull of Scarcity

The Scarcity Principle derives much of its strength from a phenomenon known as psychological reactance. This is the adverse reaction we have to any restriction of our choices.

When something is freely available and abundant, we don’t feel any limitation in our options: we can have as much of it as we want. Conversely, scarcity limits our choices, especially when whatever we desire was previously abundant.

Psychological reactance stems from loss aversion, our desire to preserve what we already have: when this freedom is restricted, we desire the item more than we did before.

“The Terrible Twos”

Anyone who has toddlers can tell you that the job of parenting becomes much harder after the child’s second birthday. Children at this age start exhibiting:

- Outright defiance (doing the opposite of what their parents tell them).

- Refusal to let their parents hold them and simultaneous refusal to be put down.

- Rejection of food, sleep, and any other source of comfort that used to be able to calm them down.

The reason this happens is that children become self-actualized at this age: they realize that they are full individuals. They come to desire autonomy and freedom of choice: and saying “no” is the most powerful expression of that autonomy. They feel that this new freedom is being taken away from them (being made scarce) by attempts to force them to eat, sleep, or clean up their toys.

Thus, psychological reactance kicks in: they strenuously resist their parents’ attempts to curb their freedom through tantrums.

The Romeo and Juliet Effect

The famous Shakespearean tragedy Romeo and Juliet tells the story of two young star-crossed lovers who ultimately choose to take their own lives than let their feuding families tear the couple apart. Romeo and Juliet, however, might just be literature’s most famous example of psychological reactance.

Psychologists have studied the “Romeo and Juliet” effect to see the role that parental interference and restriction play in driving teenage romances. One study of 140 Colorado couples showed that couples who reported parental disapproval of the relationship were more likely to want to get married.

Moreover, when the parental interference increased, so did the feelings of attraction. The lesson is clear: don’t spark psychological reactance if you’re a parent. If you don’t like your child’s significant other, your disapproval will likely drive your child right into their arms with the Romeo and Juliet effect.

The Dade County Phosphate Saga

By now, you should be getting the idea that psychological reactance makes us want what we can’t have. It’s the forbidden fruit, the scarcity that makes it attractive.

One case from Florida stands as a powerful demonstration of this concept on a community-wide scale. In the early 1970s, Dade County, Florida (containing Miami) banned the use and possession of phosphate in cleaning products. The reaction of residents was classic psychological reactance: they began importing phosphate cleaners in droves, often resorting to smuggling and hoarding!

Not only did they start consuming more phosphate cleaners, they also started changing their attitudes and opinions about these products. The majority of Miami consumers came to see phosphate cleaners as being better products than they had before.

Psychological reactance produced the desire and then people retroactively assigned positive attributes to the product to justify that desire.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Robert B. Cialdini's "Influence" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Influence summary :

- How professional manipulators use your psychology against you

- The six key biases you need to be aware of

- How learning your own biases will help you beat the con men around you