This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Plant Paradox" by Steven R. Gundry. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are plant lectins? How are lectins plants’ defense mechanism? How do the chemical defenses of plants affect the animals that eat plants?

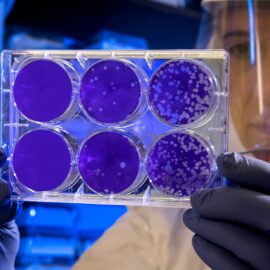

Plant lectins are the toxins produced by plants to keep predators from eating them. This chemical defense of plants can disorient or poison plant predators.

Read more about plant lectins, the toxins that are plants’ defense mechanism.

What Are Plant Lectins?

Just as animals developed defenses against their predators (e.g. skunks spray their attackers and gazelles outrun many predators), plants developed their own methods of protecting their offspring—their seeds—to ensure their species carry on. One method is to produce toxins—including plant lectins—that poison, paralyze, or disorient predators or make the plant difficult to digest. Toxins are the plant’s defense mechanism.

Plants Evolved to Spread Their Seeds

Plants produce two types of seeds: Those that the plant wants predators to eat, and those it doesn’t want predators to eat.

(Shortform note: When we talk about plants wanting a certain result, we’re not suggesting they have conscious thought, as people do. However, plants have evolved to encourage the survival and propagation of their species—just like all living things—and react to their environments, as we’ll explore in a later section.)

Seeds for Eating are Low in Plant Lectins

Fruit trees want their seeds to be eaten, so the seeds have a hard shell or coating to keep them intact throughout the animal’s digestion process; when the seed comes out in the animal’s excrement—essentially a nutrient-rich compost—it’s ready to grow. When predators eat these seeds (and later distribute them) they’re helping to spread them far and wide, which helps the plant’s chance of survival. If the fruit were to simply drop on the ground below the mother plant, those seeds would have to compete for sun, moisture, and nutrients.

However, plants don’t want predators to eat these seeds until the seeds have fully developed the hard coating to survive digestion—when the fruit is ripe. Consequently, unripe fruit is a different color (usually green) to indicate that it’s not ready yet and contains toxins (including plant lectins) designed to make predators sick. Once the fruit is ripe, and the seeds are ready for their journey, the levels of lectins drop and the fruit develops its rightful color to alert animals that it’s ready to eat.

At peak ripeness, fruit has high levels of sugar, and the type of sugar is designed to maximize the plant’s chance of propagation: Instead of glucose, which raises insulin levels and lets your body know when you’re full, fruits contain fructose, which doesn’t send that message. As a result, predators keep eating more fruit—and more seeds—raising the plant’s chance of spreading more seeds. This is one of the chemicals defenses of plants.

Since fruits are naturally in season for only a portion of the year, this benefits animals by giving them a chance to stock up on calories during those windows of time. The same used to be true for people, but now that we have access to fruit year-round, we’re eating more fruit and taking in more calories than we need.

When you buy out-of-season fruit, it’s typically grown in another country, picked unripe, shipped, and then blasted with a gas that changes the fruit’s color to make it look ripe. However, fruit that doesn’t ripen naturally never gets the message from the mother plant to lower lectin levels. As a result, when you eat fruit out of season, you’re ingesting large amounts of lectins.

Chemical Defenses of Plants for Naked Seeds

In contrast to fruit, plants that grow in open fields don’t want their seeds to be eaten. These plants—including grasses and vines—don’t benefit from their seeds being carried far and wide; instead, they want the seeds to drop and grow in place, so that when the mother plant dies during winter, the new plants will replace it in spring.

In order to deter predators from eating and spreading their seeds, these plants use toxins to weaken, paralyze, or sicken predators. In addition to plant lectins, which disrupt communication among cells, these toxins include:

- Phytates (or antinutrients), which block the body’s absorption of minerals

- Trypsin inhibitors, which inhibit digestive enzymes and harm the predator’s growth

- Tannins, which create a bitter taste

- Alkaloids, which also create a bitter taste (Shortform note: The author notes that alkaloids are found in nightshades such as tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants, and peppers, which he says are all highly inflammatory. However, evidence doesn’t support that nightshades are inflammatory and, in fact, alkaloids have been shown to be anti-inflammatory.)

Plants Can’t Think, But They Can React

Although plants don’t have thought processes the way humans do, these behaviors show that they can react to their environment and act to encourage their offsprings’ survival.

When a bug is eating leaves on one side of a plant, that plant will double the production of plant lectins on the other side of the plant almost immediately to deter the predator from eating even more. Similarly, one study of thale cress showed that the plant could detect when a caterpillar was eating one of its leaves and reacted by increasing the production of mildly toxic oils and sending them to its leaves.

Additionally, researchers have found that plants have a “clock gene” that recognizes the time of day and produces more toxins at times when their predators are more likely to be looking for food.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Steven R. Gundry's "The Plant Paradox" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Plant Paradox summary :

- Why eating more vegetables isn't enough, and why some vegetables are toxic to your body

- The science behind lectins and how they tear apart your body, making you fat and sick

- The 6-week program to get your body back on healthy grack