How wealthy was the Mughal empire? Why were the English the deferential party in the Mughal trade relationship?

In The Anarchy, William Dalrymple charts the rise of the English East India Company. He sets the stage by discussing conditions in India during the 17th century and what made it so attractive to British merchants.

Read more to understand how England took notice of the wealth in India and began trading within the powerful Mughal empire.

England Sets Its Sights on India’s Wealth

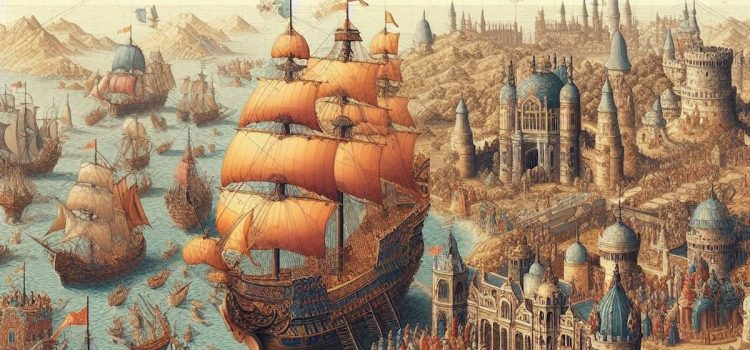

Dalrymple explains that English traders were attracted to India’s vast wealth. By the 16th and early 17th century, the Mughal empire in India was one the richest on earth, second only to Ming China. The Mughals were a powerful Muslim ruling class that governed most of what’s now modern India through a network of tax collectors and officials backed by vast armies. Nobles, called Nawabs, ruled individual provinces and sent tribute back to the capital in Delhi. With India’s fertile soil for agriculture, vast workforce, and highly developed culture of artisans, the Mughal empire had become a major exporter of textiles and spices. Mughal trade attracted European powers, including England.

Britain Sets Up Shop in Mughal India

Dalrymple asserts that, in the 17th century, the East India Company (EIC) was constrained by the power of the Mughals and carefully deferred to their authority. The EIC secured rights to build trading forts only after King James I of Great Britain sent an envoy to negotiate with the Mughal emperor Jahangir. Jahangir saw trade with Britain as a low priority. He rejected the company’s bid for an exclusive trade deal that would exclude Britain’s European rivals, but he eventually granted permission to trade.

(Shortform note: Jahangir’s foreign policy focused largely on maintaining relationships with the large Islamic empires to his West: the Ottomans, Uzbeks, and Persians. The Mughals fought the Persians during Jahangir’s reign, negotiating a peace treaty after conceding the city of Kandahar. Jahangir considered an alliance with the Ottomans and Uzbeks to counter Persian power, but he died before he could carry out his plan. Jahangir likely saw foreign relations with Britain as a low priority because the distant island nation was mostly uninvolved in the conflicts that defined his foreign policy concerns.)

Throughout the 17th century, the EIC carried out trade and quietly built more trading forts along the shores of India while remaining deferential to Mughal rule. Dalrymple explains that the Mughals commanded enormous armies and the British were in no position to cross them. The British took military action against the Mughals only once during this time. The Mughals retaliated by seizing most of the British forts, and the EIC had to apologize and renegotiate permission to continue trade.

(Shortform note: From the 15th through the 17th centuries, European nations conducted most of their overseas trade through seaside forts, which were known as “factories” at the time. These fortified locations provided markets, warehouses, customs, defense, and even governance for European merchants and explorers. Though they were established under the rule of local nations, historians now see these forts as the precursors to European colonialism in Africa, Asia, and the Americas.)

The Mughal Empire Begins to Collapse

Around the early 18th century, the Mughal empire began to collapse. Dalrymple attributes this collapse to a wide range of forces. One by one, provincial rulers began cutting ties with the capital. The independent provinces stopped sending tribute, undermining the empire’s finances. This fractured India into competing regional powers, inaugurating a period of war and instability, paving the way for the ascension of the East India Company’s power.