This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Silk Roads" by Peter Frankopan. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How did Islam start? What made it grow so successfully? What difference did the Crusades make?

In The Silk Roads, historian Peter Frankopan writes about Islam in the Middle Ages in the context of the relationship between the East and the West. He discusses how Islam started and grew, the Abbasid Caliphate, and the Crusades.

Keep reading for this brief but engaging history.

Islam in the Middle Ages

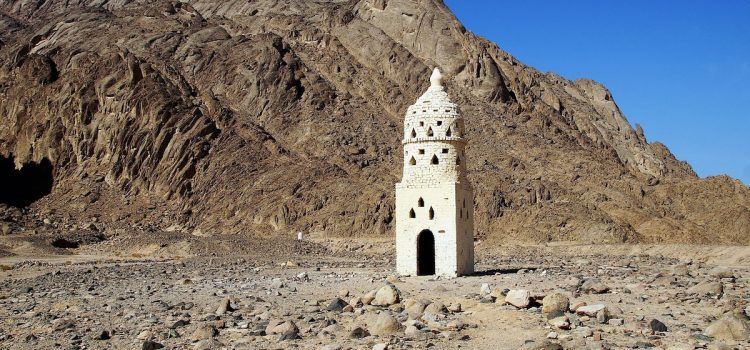

Frankopan writes that the rise of Islam in the Arabian peninsula would once again prove in spectacular fashion that the East—in this case, the lands that comprise the modern Middle East—was the center stage in global religious, political, and cultural developments. He shares the history of Islam in the Middle Ages in the context of the Silk Roads.

Islam’s Popular Appeal and Military Success

In 610 CE, the prophet Muhammad, living in the city of Mecca on the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula (present-day Saudi Arabia), first recorded his revelation from the angel Gabriel, who told him to preach the word of the one God, Allah. Frankopan argues that Muhammad’s message of spiritual and material salvation for the faithful and punishment and damnation for unbelievers found willing adherents in a region disillusioned with perceived failures of the old gods, riven by religious factionalism, and scarred by warfare.

Islam attracted followers by appealing to Arab tribal solidarity, emphasizing the common interests and experiences of the tribes of southern Arabia—in marked contrast to the powerful neighboring Byzantine and Persian Empires, both of which sought to control and dominate the region by playing local tribes against one another. Islam also attracted local adherents through its roots in the Arabic language, while its relative tolerance of religious minorities helped the new religion win crucial allies.

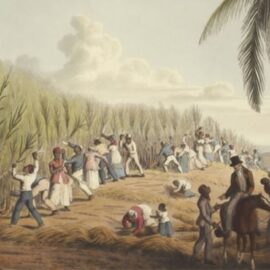

(Shortform note: One reviewer has argued that Frankopan underplays the often violent and intolerant nature of Islam’s stunning conquest of much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. In particular, Frankopan gives little attention to the Muslims’ massacre and enslavement of Jews during the sixth century, including incidents like the 627 CE extermination of the Jewish Banu Qurayza tribe of Medina, whom the prophet Muhammad ordered to be eliminated after the tribe participated in a revolt against Muslim rule. However, a growing number of Islamic scholars question the historicity of this episode.)

Stunning military success further convinced people of the power of the new religion, as Muhammad’s armies conquered the overextended and weakened Persian state in the early seventh century and seized North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and the Balkans.

(Shortform note: The Persian dynasty toppled by the Muslims was the Sasanian Empire, which at the time was the longest-lived empire of ancient Persia, ruling from 224-651. The Sasanians left a lasting legacy that deeply influenced both Byzantine and Islamic art, religion, and politics. Important contributions from the Sasanian period include their state sponsorship of Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions and a significant influence upon Islam and Christianity; and the development of the Babylonian Talmud, the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and a product of the intellectual and theological cross-pollination between Jewish and Persian scholars during the Sasanian period.)

The Wealth of Baghdad

Muhammad’s armies founded Islamic states—known as caliphates—in the wake of his conquests, starting with the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661) and the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750).

But, it was the third caliphate—the Abbasid Caliphate, centered on the wealthy and cultured new city of Baghdad—that linked together the wealth of Central Asia, North Africa, and Southeastern Europe, creating a new network of trade and tribute. Frankopan writes that Baghdad was the cultural, scientific, literary, and artistic center of the Islamic world in the eighth and ninth centuries. It was here, he observes, that Arab scholars preserved classical Greek and Roman learning in medicine, philosophy, and mathematics—much of which had been lost to Europe during the Dark Ages, when the Christian kingdoms of Western Europe were largely mired in poverty, backwardness, and illiteracy.

(Shortform note: Other scholars argue that, in addition to Muslim scholars in Baghdad and elsewhere in the Abbasid Caliphate, early medieval Irish monks and clergymen, at the western extreme of Europe, played a crucial role in preserving classical literature and culture. In How the Irish Saved Civilization, Thomas Cahill writes that Greek and Roman works of poetry, theology, science, and epic literature would have been lost without the work of Irish monastics like St. Patrick and St. Columba, who carefully and painstakingly hand-copied the ancient manuscripts at remote monasteries like Clonard Abbey, Killeany, and Glendalough.)

The Crusades: New Connections Between East and West

As Frankopan writes, the success of the Muslim conquests and the subsequent rise of powerful Muslim states threatened the Christian Byzantine Empire.

In 1099, the Byzantine emperor, via the pope, appealed to the Catholic Christians of Western Europe for aid.

This was the beginning of the Crusades—the centuries-long religious struggle waged by European Christians against the Muslim states of the Middle East for control of the Holy Land.

Thanks to the conquests of the Crusaders, Frankopan argues, Europeans gained new access to the rich markets and trade routes of the East, and European scholars marveled at the scientific, literary, theological, and cultural achievements of the Muslim world.

Moreover, the Crusades shook Western Europe out of the isolation in which it had languished since the fall of the Western Roman Empire and gave the new, rising monarchs wider ambitions about their role in the world. Thus, writes Frankopan, the Crusades helped lay the groundwork for the European global imperialism that would follow in the centuries to come.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Peter Frankopan's "The Silk Roads" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Silk Roads summary:

- Why the Silk Roads have always been history’s crucial connection point

- Why understanding the East is crucial to our understanding of the world

- A history of the Silk Roads, from ancient times to the 21st century

We’re in the age of nanotechnology and space travel, but we still believe in the nonsense of the superstitious late Middle Ages.

Islam did not originate in the Hijaz desert. There is no archaeological evidence of life in this complete desert. No one has seen the famous prophet. He’s a character from late literature. The term “Arabs” did not designate an ethnic group but a way of life of nomadic plunderers. All the world’s nomads who lived by raiding were “Arabs”: the Bedouins, the Mongols, the Tuaregs, the Circumcellions. The meaning “Arabs” was pejorative. An insult!

Of course, as nobody had seen the famous prophet, nobody had seen the famous invasions of North Africa and Spain.

Islam is simply the evolution and radicalization of the Unitarian Christian sects, adversaries of Roman Christianity.

The whole official history of Islam is just bad literature.