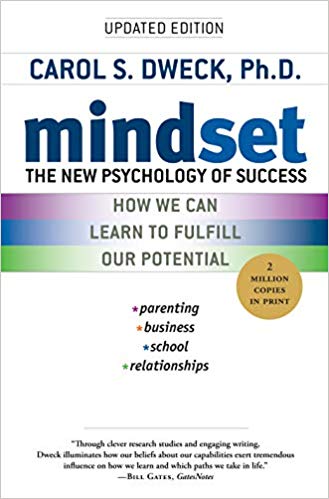

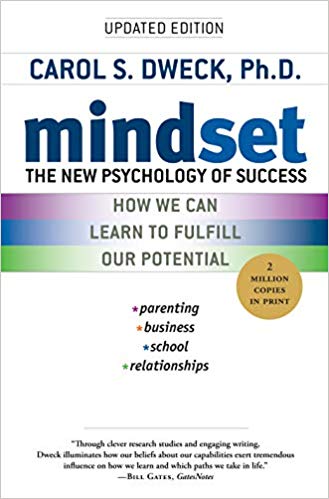

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Mindset" by Carol Dweck. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is Carol Dweck’s growth mindset? How can you better incorporate the concept of the growth mindset in schools?

We’ll cover why student achievement starts with fostering a growth mindset in schools, and how to ensure all students develop a growth mindset.

Growth Mindset in Schools

Achievement in school starts with the growth mindset. Researchers measured students’ mindsets as they transitioned to junior high school, which is a particularly challenging time for adolescents, then followed them for two years.

The students started out with similar grades but after the transition with its new challenges, the grades of fixed-mindset students declined, while those of growth-oriented students improved.

The fixed-mindset students tried to rationalize their poor grades with explanations such as “I’m no good at math” or they blamed the teacher. They viewed the change to junior high as threatening because it could expose them as failures. They protected themselves from failure by not trying (the low-effort syndrome).

In contrast, the growth-minded students faced the tougher environment by doubling down and working harder. They welcomed the opportunity to learn what they like and might achieve. This demonstrates the importance of teaching the growth mindset in schools.

Growth Mindset in Schools: College

The transition to college is another crisis point in young people’s development. They go from being top students in their high school to having to prove themselves among top students from many high schools. Even in college, it’s still important to teach the growth mindset in schools.

Anxiety is especially high in the pre-med classes. In the study of pre-med students facing the gateway chemistry course, there were big differences in how students with each mindset approached the course and in their achievement.

Everyone studied, but the two groups studied differently. The students with fixed mindsets studied the way many students have learned to study: they re-read the text and their notes and memorized as much as they could. They believed they’d done everything possible — maybe they just weren’t good at chemistry. But instead of memorizing the material, the growth-minded students looked for themes and principles across lectures. They worked to understand their mistakes — they wanted to learn, not just to excel on a test.

As a result, the growth-oriented students got higher grades than the fixed-minded students. The more difficult the material became, the harder they worked, motivating themselves and staying positive.

Mindset Versus Ability

Mindset clearly can have a huge impact on learning and achievement. It’s clear we should be teaching the growth mindset in schools.

Ability is also a factor. All children aren’t created equal — some have greater ability and become prodigies by building on their ability, seeking challenges and pursuing a love of learning. However, everyone has interests that can grow into abilities if nurtured. As noted previously, no one really knows anyone else’s potential. While abilities vary, your mindset in the classroom determines where you go with them.

There are many examples of great academic achievement by children with few resources, who were thought to have dead-ended until a growth-minded teacher showed them that they could learn. For example, as recounted in the movie Stand and Deliver, teacher Jaime Escalante taught advanced calculus to inner-city Hispanic high school students in Los Angeles.

Other teachers had concluded they couldn’t learn, while Escalante asked himself how they could learn and how he could teach them. His students ultimately excelled and more of them took advanced placement tests than did students from elite science high schools. Escalante’s experience raises the question of how much is lost when we underestimate students’ potential.

Researcher Benjamin Bloom, who studied outstanding achievers, concluded that almost all people can learn under the right conditions, including support, commitment, and motivation.

Messaging and Growth Mindset in Schools

How do you foster a growth mindset in schools? The first step is to understand what children hear when we talk to them.

Children with fixed mindsets hear judgment from their parents and teachers — it feels as though their abilities are always being measured.

To understand children’s thinking, researchers asked them several questions. Here are the responses from both the fixed-minded and growth-oriented kids.

Question #1: Imagine that your parents are happy when you get a good grade. Why would they be happy?

- Fixed-minded children responded along the lines of: “They were happy to see I was smart.”

- Growth-minded children said a good grade meant they’d buckled down and worked hard.

Question #2: Imagine that your parents talked with you about your performance when you did poorly. Why would they do this?

- Fixed-minded children responded that their parents probably were worried that they weren’t smart, that bad grades might mean they weren’t smart.

- Growth-minded children said their parents likely wanted to teach them better study methods for the future.

Mindsets in the Classroom

Children need growth-minded teachers and coaches to teach them the growth mindset in schools and help them learn to develop and succeed. Famous teachers Marva Collins and Rafe Esquith taught from a growth mindset. They believed in the growth of ability and intellect, and they loved both learning and fostering development and learning in their students. They created a nurturing environment in which they emphasized standards and hard work.

Examples: Growth Mindset in Schools

Marva Collins taught Chicago children who had reached a dead end. For instance, one boy had attended thirteen schools in four years and another had been kicked out of a mental health center. On her first day, Collins told the students: ‘Welcome to success. But success is not coming to you, you must come to it.’ This is a great example of incorporating the growth mindset in schools.

Her students worked all day with only a short lunch break. They wrote every day and, as their skills grew, they tackled increasingly difficult material. When 60 Minutes did a program on the school, the children expressed pride in working hard. One student told reporter Mike Wallace that he liked the hard work “because it makes your brain bigger.” This is a key principle of the growth mindset in schools.

Similarly, Rafe Esquith taught Los Angeles second graders form high-crime areas. Many had family members with drug, alcohol, and emotional problems, so the children didn’t get much support at home. To emphasize the value of effort, Esquith regularly reminded them of how much they’d learned and how difficult concepts had gotten easier with practice. He told them he wasn’t any smarter than they were, but knew more because he worked at learning. His motto was, “There are no shortcuts.”

Standards and Nurturing

Collins set extremely high standards.

For instance, three- and four-year-olds used a vocabulary book for high school students; seven-year-olds read The Wall Street Journal. However, she also created an atmosphere of love and concern. She also told the children she would love them even when they didn’t love themselves.

A caring, nonjudgmental learning environment is important for performance. Researchers who studied 102 high-achieving musicians, artists, athletes, and mathematicians found that their first teachers were warm, accepting, and committed to teaching them. The environment is important for fostering a growth mindset in schools.

Like Collins, Esquith maintained an atmosphere of affection and personal commitment to his students, while setting high standards. He decried what he viewed as slipping standards in many schools, noting that educators don’t help children when they gloss over deficiencies — they consign them to continued failure and a lifetime of low-wage jobs. His fifth grade reading assignments included: Of Mice and Men, Native Son, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, A Separate Peace, and To Kill a Mockingbird. He required his sixth graders to pass an algebra final that eighth and ninth graders in most schools would struggle with.

Besides setting high standards, growth-minded teachers show students how to meet them. Collins didn’t just tell her students to read Shakespeare’s MacBeth. She and her students read and talked about each line together. Esquith spent considerable time planning passages for each student to read in class, so that a shy child would succeed and a more advanced student would be challenged. He met with students before and after school and even on vacation. His goal was for students to be able to learn and think on their own. These are great examples of how to teach students the growth mindset in schools.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Mindset" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Mindset summary :

- The difference between a growth and a fixed mindset

- How a fixed mindset keeps you back throughout your life: education, relationships, and career

- The 7 key ways to build a growth mindset for yourself