This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Hot Zone" by Richard Preston. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the Ebola book The Hot Zone about? What is a hot zone, and how can Ebola outbreaks spread in these zones? What does The Hot Zone Ebola book say about containing future outbreaks?

In the Ebola book The Hot Zone, journalist Richard Preston explains what a hot zone is. He explores the various Ebola outbreaks, their origins, and their impacts.

Read more about this groundbreaking Ebola book and what it says about the different Ebola hot zones.

The Hot Zone: Ebola Book Defines Ebola

The Ebola virus is greatly feared, but not well understood. Scientists know the virus jumped to humans from African monkeys, but they don’t know where the virus originated or how it infected the monkeys in the first place.

Ebola virus has appeared only a handful of times and, despite being highly infectious, it has never spread to become a full-blown epidemic. However, Ebola’s brutal attack on victims’ bodies, astronomical kill rates, and ability to mutate make it a constant potential threat.

The Hot Zone explores how Ebola and its family of viruses affect humans, the history of known outbreaks, and the possibility of a future epidemic.

The Filovirus Family

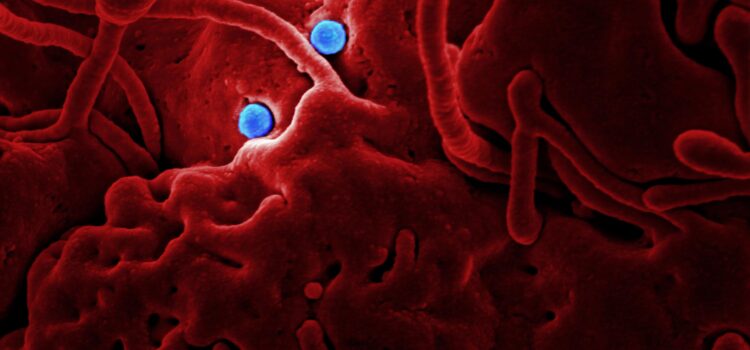

Ebola belongs to a family of viruses named filoviruses, meaning “thread viruses,” because they look like threads or ropes under a microscope.

There are four viruses in the filovirus family:

- Marburg, the mildest strain, with a kill rate of 1 in 4

- Ebola Sudan, with a kill rate of about 1 in 2

- Ebola Zaire, the deadliest strain, with a kill rate of 9 in 10

- Ebola Reston, the most recently discovered strain, which we’ll get to later

The Hot Zone: Ebola Book Describes Outbreaks

In The Hot Zone, Ebola is explained. and the Preston explains the hot zone definition. Simply put, the hot zone definition is any area that is considered dangerous. In viral outbreaks, the hot zone is an area that has an outbreak of the virus. The author of The Hot Zone Ebola book answers the question “what is a hot zone” in the context of each outbreaks.

1962-1976: The First Outbreaks

The first recorded outbreaks of the filoviruses occurred in a 15-year stretch in the 1960s and ‘70s. Distinct symptoms like victims’ red eyes helped doctors draw connections among the diseases.

1960s: First Marburg Outbreak

The Ebola book explains the first Ebola outbreak of a virus called Marburg. The hot zone definition is clear here, since the virus infection 31 people in a factory in Germany in 1967. But before that, between 1962 and 1965, several Ugandan villages around Mount Elgon—not far from Kitum Cave—were hit with outbreaks of an unusual disease that killed not only villagers but also monkeys. The symptoms included a strange skin rash and bleeding.

The village microbreaks went relatively unnoticed, but in 1967 a vaccine factory in the German city of Marburg experienced an outbreak that infected 31 people and killed seven.

1976: First Ebola Sudan Outbreak

The first known case of Ebola was in a man known as Yu. G., in the summer of 1976. Yu. G. lived in a southern Sudan, about 500 miles from Mount Elgon.

Yu. G. never went to the hospital—he died in a cot at home—nor was he well known outside his family and coworkers. Nevertheless, he set off an outbreak of the virus that was later named Ebola Sudan.

No one knows where or how Yu. G. contracted the virus, but it soon spread to a few of his coworkers, from whom it spread to friends, families, and a nearby hospital. From the hospital, the virus took off through the reuse of dirty needles, meeting the hot zone definition.

Ebola Sudan killed hundreds of people in central Africa. The virus’s 50 percent kill rate was comparable to the bubonic plague of the Middle Ages.

1976: First Ebola Zaire Outbreak

Just two months after the Ebola Sudan outbreak ignited, Ebola Zaire appeared 500 miles away, in the mostly rural Bumba Zone of northern Zaire. Ebola Zaire was even deadlier, with almost double the kill rate of Ebola Sudan.

The virus appeared at the rural Yambuku Mission Hospital, which was run by Belgian nuns. No one knows who the first human was to contract Ebola Zaire, or from what—whether animal meat, insect blood, a spider bite, or something else. The hospital’s practice of reusing dirty needles made it impossible to know which patient first brought the virus into the hospital.

Just a drop of infected blood is enough to transmit Ebola, so the virus quickly spread among the hospital’s nurses, injection patients, and their families, hitting 55 surrounding villages at once.

1980: The Case of Charles Monet

In 1980, Charles Monet, a French expatriate living in Western Kenya, spent New Year’s Day exploring Kitum Cave with a friend. A week later, he began getting sick.

After several days, Monet’s coworker took him to a nearby hospital. The doctors didn’t recognize the illness, nor did they know how to treat it. When antibiotics didn’t help, they suggested he go to the best private hospital in East Africa, Nairobi Hospital. Sick as he was, Monet was still lucid and mobile, so he got in a taxi and headed to the airport.

As soon as Monet boarded the flight, he unknowingly exposed the world to the virus: He was in a cramped, probably full plane with people from anywhere in the world, traveling to anywhere in the world. Modern air travel routes make it possible for a disease to spread anywhere in the world within 24 hours.

1989—Ebola Appears in the U.S.

The mysteries surrounding filoviruses’ source and transmission intensified when Ebola appeared in the U.S. two years later.

In October of 1989, 100 wild monkeys were shipped from the Philippines to the Reston Primate Quarantine Unit in Reston, Virginia. The facility was an arm of Hazleton Research Products, a company that imported and sold lab animals. When imported wild monkeys arrive in the United States—typically for laboratory testing—they must be held in quarantine for a month before they’re sent anywhere else in the country.

When this shipment of monkeys arrived, two were already dead. A few dead monkeys wasn’t unusual, but in less than a month, 29 of the 100 monkeys had died.

Geisbert Recognizes Filovirus Particles

After the holiday, Geisbert inspected the supposedly contaminated cells under his electron microscope. He recognized what he saw: The cells were bulging with rope-like viruses, just like he’d seen in pictures of samples from Cardinal’s blood. It was a filovirus, but the threads were less curled than Marburg virus particles.

Geisbert printed the images and showed Jahrling. Jahrling recognized the signature thread-like shapes. Although there were some differences between the cells in Geisbert’s photos and the images of Marburg in the textbook they consulted, it was close enough to be concerning.

The Army Sterilizes the Monkey House in The Ebola Book

What is a hot zone when it comes to animal outbreaks? When there was an outbreak amongst monkeys in a research lab, officials immediately declared it a hot zone. Within a few days, the media had caught wind of the viral outbreak at Reston. On the morning of the Army’s first sterilization operation at Reston, the front-page story in The Washington Post was about the discovery of Ebola in the monkey house.

Peters had given the reporter a quote for the story, speaking carefully to avoid raising panic and to assure the public that everything was under control. The Army had to act as cautiously and inconspicuously as possible during its mission to avoid making a scene at the Reston facility.

The CDC Names Ebola

The American Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was eager to get a sample of the nun’s blood as well. Karl Johnson, the head of the CDC’s Special Pathogens Branch—which investigated new and unknown viruses—called a friend at the English lab to ask for a small sample of the blood.

The English researcher agreed and sent a tiny amount of black, tarry blood in glass vials. Through electron-microscope photos, CDC researchers saw that the virus resembled Marburg, but it tested negative for Marburg and other known viruses. They were facing something entirely new. Johnson named the virus Ebola, because the outbreak happened around Zaire’s Ebola River.

Johnson and several other CDC doctors flew to Geneva to tell the World Health Organization what they had found. Then the doctors continued on to Zaire and Sudan to try to stop the outbreaks.

When the doctors arrived in Africa, they discovered that villages had taken their own measures to limit the virus’s spread, including:

- Reverse quarantine, which entailed blocking the road leading to the village to prevent anyone from bringing the virus into the village

- Quarantining victims in isolated huts on the outskirts of the village, and, in some cases, burning the huts after the victims died

Presumably, these measures played a major role in preventing the virus from spreading further and sparking a major epidemic.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Richard Preston's "The Hot Zone" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Hot Zone summary :

- The many different strains of Ebola, including the deadliest kind with a kill rate of 90%

- How scientists unraveled the mystery of a new strain of Ebola

- How Ebola could become airborne, becoming one of the deadliest viruses known