This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "How Emotions Are Made" by Lisa Feldman Barrett. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Are there cultural differences in emotions? How does your culture shape your emotions? Are some emotions unique to certain cultures?

Lisa Feldman Barrett says emotions don’t necessarily cross borders—cultural differences shape how you experience and express emotions. According to Barrett, universal emotions are mostly a myth because the experiments they’re based on were flawed.

Keep reading to learn why there are cultural differences in emotions, according to Barrett’s research.

How Cultural Differences Create Unique Emotions

Myth: People all over the world recognize and share the same emotions.

Reality: According to Barrett, the experiments on which this idea is based were flawed. There are, in fact, cultural differences in emotions, as expressed through unique words describing emotion concepts that do not exist in other cultures.

Early Experiments Concluding That Emotions Are Universal Were Flawed

Barrett points out that there are thousands of studies claiming that cultural differences don’t impact emotions (i.e. emotions are universal). Popular media reinforces the idea that not only do specific facial expressions correspond with specific emotions, but those emotions are recognizable by people in vastly different cultures all over the world. Everyone recognizes that a frown means sadness, these studies say, and because we all recognize it, we also experience and share the same concept of sadness across cultures.

(Shortform note: Charles Darwin’s 1872 book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, is one of the first written texts to put forth the theory of universal expressions, and proponents of the belief still cite it today, despite evidence to the contrary.)

Early experiments on cultural differences in emotions involved a remote African culture, the Himba, and purported to show evidence of universal emotion recognition. Rather than asking subjects to match facial expressions with emotion words, the experiments asked them to match brief emotion stories with emotion sounds, such as laughs, grunts, snorts, etc.

But it came to light after the experiments were conducted that the reason the subjects were getting the answers right was that the researchers were effectively coaching the subjects to learn the correct Western-style emotion concept before they were asked to match an emotion story with an emotion sound. The subjects weren’t recognizing a universal emotion, they were learning foreign concepts of emotion and then applying what they had learned.

When Barrett and her colleagues conducted the same experiment without the added teaching time, there was no indication of universal emotion recognition.

(Shortform note: Other early studies of emotion support Barrett’s claim that emotions vary across cultures. One of the first researchers to document cultural differences in emotion was pioneering cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead. In her 1928 book Coming of Age in Samoa, Mead described unique emotional phenomena she observed while doing field work in a small village on an island in Samoa. She decried the arguments of Darwin in the previously mentioned The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, a debate in which Paul Ekman himself discusses in an afterword to a later publication of the book.)

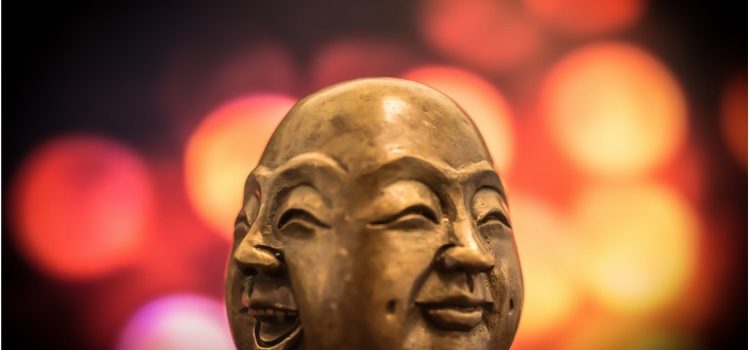

Different Cultures Have Different Emotion Concepts

Not only are emotions expressed differently from person to person within the same culture, but different cultures have very different emotion concepts, expressed as words. As the flawed experiments with the Himba people showed, certain Western-style emotion concepts don’t exist in other cultures. Sadness isn’t the same across cultures; in Tahiti, for example, there is no concept of sadness. Tahitians have the concept “pe’ape’a,” which combines the Western concepts of ill, troubled, fatigued, or unenthusiastic. Without the concept of sadness, you can’t experience sadness. You need an emotion concept to experience or perceive an emotion.

(Shortform note: Albeit fiction, the connection between language and emotions is a prominent theme of George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984. In it, the “thought police” systematically remove words from the culture as a way of suppressing emotions, which they knew could lead to uprisings. The idea that emotions can’t exist without a way to express them (an emotion concept) supports the notion that emotions could be expressed differently from culture to culture.)

Examples of Cultural Differences in Emotion Concepts

Barrett points out that non-Western cultures also have emotion concepts that the West doesn’t, such as the Japanese “age-otori,” which is the feeling of looking worse after a haircut, or the Tagalog “gigil,” which means the urge to hug or squeeze something that is unbearably adorable. These emotions are just as real as more commonly recognized emotions like happiness, even though the emotion concepts don’t exist in other cultures.

Emotion concepts can be combined to form new concepts. So, for example, although Westerners don’t typically feel the exact emotion of “age-otori,” they can combine the concepts of disappointment, frustration, and perhaps even anger or insecurity at looking worse after a haircut, in order to understand the Japanese emotion concept. Once a foreign emotion concept is incorporated into a new culture—for example, the German “schadenfreude” is now commonly used in the US—it’s easier for people who comprise that culture to identify and experience that particular emotion.

(Shortform note: By the same token, certain emotion concepts that existed in ancient times have since disappeared and have no precise modern equivalent. One such emotion concept, explains Tiffany Watt Smith in The Book of Human Emotions, is “acedia,” used by cultures living in the deserts of Western Egypt in the fourth century. Acedia meant an emotional crisis, usually striking between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m., when the heat of the desert was at its worst; it encompassed listlessness, irritability, desolation, and despair. Indeed, until the sixth century, acedia was considered one of the deadly sins. Some of its symptoms were later absorbed into the moral vice of sloth, while others became what is now considered depression.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Lisa Feldman Barrett's "How Emotions Are Made" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full How Emotions Are Made summary:

- A deep dive into what emotions really are and where they come from

- How some cultures have different emotions than others

- The difference between feelings and emotions