This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Think Like a Rocket Scientist" by Ozan Varol. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

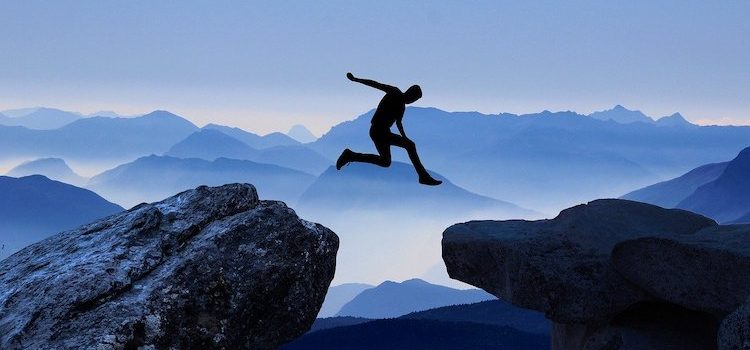

How comfortable with uncertainty are you? Is a fear of uncertainty holding you back?

Uncertainty plays a crucial role in science because things often don’t conform to scientists’ expectations. When things don’t go according to plan, scientists learn something new. They are comfortable with uncertainty, because they know it can lead to amazing discoveries.

Read more to learn how comfort with uncertainty can lead to big things in your own life.

Comfort With Uncertainty

According to Think Like a Rocket Scientist by Ozan Varol, the path to achieving the impossible is rarely clear-cut—so to reach those goals, we have to get comfortable with uncertainty. However, as Varol describes, this is difficult because humans are biologically programmed to resist uncertainty. For our earliest human ancestors, uncertainty could be a death sentence: If they heard a twig snap, the ones who were certain the sound came from a predator would have time to run, while the ones who languished in uncertainty would become that predator’s next meal. Thus, the people who were not comfortable with uncertainty lived long enough to pass their genes down to us. (Shortform note: In Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman argues that people actually fall on a range of how much uncertainty they can tolerate. Some people are naturally bold and can comfortably tolerate more uncertainty than people who are naturally timid.)

How Rocket Scientists Approach Uncertainty

However, Varol argues that while comfort with uncertainty can difficult, it’s also the path to the greatest discoveries. According to Varol, uncertainty plays a crucial role in science through anomalies—things that don’t conform to scientists’ expectations. Anomalies drive science because when everything follows the model or otherwise goes according to plan, we don’t learn anything new; however, when something doesn’t go the way we expect, it reveals the limits of our understanding and forces us to figure out what’s really going on. (Shortform note: Unmet expectations drive business success as well as scientific discovery. In Good Strategy Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt describes how noticing an anomaly prompted Howard Schultz to found Starbucks. While visiting Italy, Schultz became familiar with Italian coffee houses and realized that there were no comparable businesses in the United States.)

How You Can Get Comfortable With Uncertainty

Varol offers two ways to get comfortable with uncertainty in order to make big leaps:

1) Nail down what you do and don’t know for sure. Contain the uncertainty by listing exactly what you know about a problem or situation. Whatever’s left is the real uncertainty, which is probably smaller than it looked before delineating. Then, ask yourself: What’s the worst-case scenario? What’s the best? How likely are they?

For example, imagine you want to start selling a new type of product. The things you know might include the specifications of the product, how much that product will cost to manufacture, the price you want to give the product, and the fact that your competitors’ equivalent product is successful. An uncertainty that remains is the demand for your version of the product.

In the worst-case scenario, nobody would want to buy your product; in the best case, the product would be a roaring success. On balance, the most realistic scenario is moderate success; since people buy your competitor’s offering, there’s clearly some demand for that type of product. However, roaring success is unlikely, at least immediately, if your competitor has got a hold on the market. Ultimately, there’s still some uncertainty regarding the success of your product, but at least you’ve got a rough idea of how launching it may pan out.

2) Add a degree of redundancy to the important parts of your life. Redundancy is a safety measure—a backup to make sure things work out okay even if Plan A goes wrong (for example, it’s wise to back up all of your digital information in case something happens to your computer).

However, redundancy helps only up to a point, and too much redundancy can introduce a dangerous amount of complexity to a system. (Shortform note: In Antifragile, author Nassim Nicholas Taleb describes how humans are biologically redundant: We have backups of several important organs, such as lungs and kidneys, so that we’ll survive even if one fails. However, if we had more than two of each, the potential for problems or infections might outweigh the benefits of redundancy.)

| Reduce Uncertainty the Fermi Way Nailing down what you do and don’t know for sure is similar to the process of solving Fermi problems. Fermi problems are a specific type of thought experiment popularized by physicist Enrico Fermi in which you attempt to estimate an unknown quantity without any additional information (for example, “How many piano tuners are there in New York City?”). In Superforecasting, psychologist Philip Tetlock argues that the best approach to solving Fermi problems is to break the question down into smaller and smaller questions, then decide which of those small questions you can answer and which you can’t. This process reduces the overall uncertainty of the original question down to a few smaller, manageable uncertainties for which you can make educated guesses. |

Getting comfortable with uncertainty is one way you can think like a rocket scientist.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ozan Varol's "Think Like a Rocket Scientist" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Think Like a Rocket Scientist summary :

- How to solve problems like billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk

- Why you should treat your ideas like scientific hypotheses

- How to bounce back from failure and avoid complacency after success