This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton M. Christensen. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are some case studies in innovation? How do different case studies in innovation teach important lessons for businesses?

Case studies in innovation can come from any industry. One of the most robust case studies in innovation is the disk drive industry, which saw several disruptive innovations over the years.

Read on for one of the interesting case studies in innovation.

Disk Drives and Case Studies in Innovation

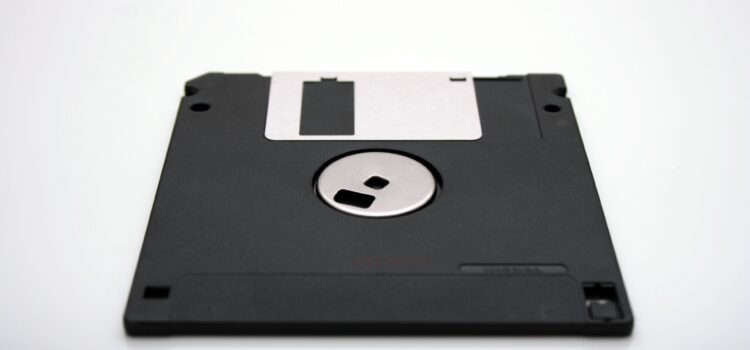

There were only a handful of disruptive changes in the disk drive industry, but they caused established firms to crumble. The most significant of these changes was the shrinking of disk drives. This serves as one of the case studies in innovation.

Two of the most important characteristics of disk drives are physical size and capacity. The industry was in a constant push to fit more data capacity on smaller drives.

In the 1970s, the high-capacity 14-inch drive was standard for mainframe computers, the huge machines used by large businesses for processing data and transactions. Between 1978 and 1980, entrant firms introduced a disruptive technology: a smaller, lower-capacity 8-inch drive.

The 8-inch drive didn’t have enough capacity for mainframes, but it was perfect for the emerging market of minicomputers—mid-sized servers used for business, scientific projects, and databases—which were a step down in size and power from mainframe computers.

At first, the 8-inch drives cost more per megabyte of capacity, even though the drive’s total price was lower than the 14-inch drive. The market tolerated the higher price-per-megabyte because it valued the drive’s smaller size.

Over time, 8-inch drive manufacturers improved capacity and reduced costs so much that the 8-inch drives eventually had a lower cost-per-megabyte than the 14-inch drives. Additionally, the 8-inch drives began invading the 14-inch drives’ market: The 8-inch drives’ capacity had increased enough to suit low-end mainframe computers, eventually pushing 14-inch drives out of the low-end mainframe market.

Among 14-inch drive manufacturers, two-thirds never entered the 8-inch drive market—and those that did were two years behind the 8-inch startups. Although the established firms that entered the 8-inch market had products that performed just as well, they couldn’t compete with the entrant firms. Eventually, every 14-inch drive manufacturer failed.

The 14-inch drive manufacturers hesitated or failed to enter the 8-inch market because their mainframe computer customers didn’t want smaller drives. Mainframe computer makers wanted more capacity at a lower cost-per-megabyte, and 8-inch drives couldn’t offer that—at first. Ultimately, listening to their customers led to the 14-inch firms’ demise.

This pattern repeated multiple times in the evolution of the ever-shrinking disk drives.

The 5.25-Inch Drive

When the entrant Seagate Technology created the 5.25-inch drive in 1980, it had a sixth of the megabyte capacity of 8-inch drives and five times the access time (the higher the access time, the slower the computing speed).

Minicomputer manufacturers weren’t interested in the innovation, so Seagate had to find another market. The company turned to the emerging market of personal desktop computers, where the drive’s inferior capacity was less important than its smaller size and lower total price.

As in the transition from 14- to 8-inch drives, the established 8-inch firms that eventually produced 5.25-inch drives were about two years behind entrant firms. And half of 8-inch makers never entered the 5.25-inch market and eventually failed.

As the capacity of the drives increased, they eventually became sufficient for minicomputer and mainframe manufacturers. Again, the disruptive innovation began in an emerging market and eventually invaded the established market.

The 3.5-Inch Drive

The 3.5-inch drive was created by a company called Rodime in 1984, but the technology took off when the firm Conner Peripherals brought it to market in 1987. Similar to previous evolutions, this drive was physically smaller and offered less capacity than existing products.

Conner found a market in new portable and laptop computers, which valued the drive’s smaller size, lighter weight, and decreased power needs.

Seagate—the innovator of the 5.25-inch disk drive, and now an established firm—could have beat Conner to the market, but the company fell into the trap of listening to its customers. In 1985, Seagate’s engineers introduced a 3.5-inch drive prototype to customers, but the desktop computer makers weren’t interested. Seagate’s executives killed the 3.5-inch project because they doubted that the smaller drives would bring in enough revenue to make it worth the investment.

However, after Conner began selling 3.5-inch drives, Seagate revived the project—but instead of targeting the emerging market of laptop manufacturers, Seagate sold the smaller drives to desktop computer makers. Although Seagate had hesitated to invest in the disruptive technology for fear of cannibalizing its existing sales, that’s exactly what happened when the company finally entered the market because it sold the drives to its existing customers.

Seagate’s mistake is a common misstep among companies facing disruptive technologies. To avoid this, established companies should adopt disruptive innovations soon after the technologies emerge, and the companies should target the disruptive products’ emerging markets, instead of trying to tailor them to existing markets.

2.5-Inch Drive: The Final of These Disk Drive Case Studies in Innovation

In 1989, an entrant firm called Prairietek introduced a 2.5-inch drive and dominated the market. But by the end of 1990, Conner Peripherals produced its own version of the drive and took 95 percent of the market.

In this case, the entrant Prairietek didn’t have the advantage over the established Conner Peripherals because the 2.5-inch drive was a sustaining—not a disruptive—technology. The smaller drive appealed to the same laptop makers that used 3.5-inch drives, so the innovation merely represented a technological improvement.

Throughout the decades of improving disk technology, each round of the case studies in innovation showed incumbents allowed themselves to be led astray by their customers’ input.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Clayton M. Christensen's "The Innovator's Dilemma" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Innovator's Dilemma summary :

- Christensen's famous theory of disruptive innovation

- Why incumbent companies often ignore the disruptive threat, then move too slowly once the threat becomes obvious

- How you can disrupt entire industries yourself