This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Black Like Me" by John Howard Griffin. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Want an overview of Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin? What were Griffin’s key takeways from his experiment?

In Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin darkened his skin to appear like a Black man, then traveled for six weeks throughout the segregated Southern U.S. In the book, he argues that his hypothesis was correct: Black Southerners faced brutal racism.

Read on for an overview of John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me book.

Black Like Me Book Overview

If you could spend several weeks in the body of someone of a different race, would you? In 1959, one man tried to do this. To write his book Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin, a white journalist from Texas, embarked on an experiment in which he darkened his skin tone to appear like a Black man, then traveled for six weeks throughout the segregated Deep South.

Griffin hypothesized that his disguise would subject him to racism, and he hoped this outcome would accomplish two main goals. First, he sought to better understand the nature of antiblack racism by experiencing it himself. Second, he hoped his discoveries about racism would convince white people that the U.S. was not the racism-free country they believed it to be.

Following his journey through the Deep South, Griffin claims his hypothesis was correct: Black Southerners faced discrimination on the basis of skin color. He made only one change to his appearance—darkening his skin—and that one alteration both limited his opportunities and subjected him to people’s racism. He published stories from his journey in Sepia magazine and later compiled these stories into Black Like Me, published in 1961.

The Question Behind Griffin’s Experiment

In Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin claims that one question drove his experiment: Was racism in the South more rampant than most white Americans typically acknowledged? He first formulated this question after reading a news report about the rising numbers of Black Southerners who wanted to commit suicide. According to Griffin, this report painted a picture of the South that contradicted the narrative most white Americans believed: that Southern race relations were harmonious. Furthermore, most white people denied that racism existed in the U.S. They associated racism with the heinous anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany—not with their own country.

| Beliefs About Racism in Post-War America In his book, Griffin focuses on describing white people’s perspectives on race relations in post-war America. Contrasting these perspectives with those of Black Americans reveals stark differences between how these two groups viewed their nation. In the late 1950s, how widespread was the belief that the U.S. was free of racism? A national poll conducted in 1956 reveals that 60% of white people believed Black Americans were treated fairly. This statistic supports Griffin’s claim that most white people denied the existence of U.S. racism. The poll also reveals that, by contrast, only 11% of Black people believed they were treated fairly. Furthermore, there were differences in how white and Black Americans compared the U.S. to Nazi Germany. As historian Ibram X. Kendi describes in Stamped From the Beginning, during World War II, Black Americans saw parallels between their oppression and the oppression of European Jews—parallels that white Americans didn’t see. During the war, the country’s largest black newspaper began the “Double V Campaign”—one “V” stood for “victory against racism at home,” and the other stood for “victory against fascism abroad.” This movement both celebrated Black people’s contributions to the U.S. military and criticized racist U.S. laws. Some historians believe this campaign paved the way for the Civil Rights Movement. |

Griffin’s Plan for His Experiment

After deciding that could answer his question by disguising himself as a Black man, Griffin reasoned that for his experiment to work, he must only change his skin color. If he experienced racism while passing as Black and otherwise remaining exactly the same, it would prove to white Americans that Black Southerners experienced prejudice solely on the basis of skin color. Therefore, Griffin planned to keep his name, as well as dress and talk as he usually did.

Griffin’s Preparation for His Experiment

To write his book, Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin took several steps to make his plan a reality. First, he enlisted the help of a dermatologist who darkened his skin using an ultraviolet lamp and pills that treat vitiligo (a skin disease). Next, Griffin obtained a dark stain that he smeared across his skin to even out his skin tone. Finally, Griffin shaved his head, since his untextured hair risked revealing his whiteness.

(Shortform note: Critics of Griffin’s methods contend that it was wrong for him to darken his skin and shave his head to try to pass as Black, no matter his antiracist intentions. They see Griffin’s disguise as an example of blackface (when non-Black people try to appear Black). For centuries, blackface has been used in performances to mock and dehumanize Black people. One critic argues that even though Griffin didn’t intend to mock nor dehumanize, his experiment was still blackface and therefore problematic. By claiming that he represented the Black experience, Griffin arguably devalued Black people’s real, complex experiences—ones that result from a lifetime of being Black, not several weeks of appearing Black.)

Griffin also prepared for his experiment by crafting an itinerary and a plan for how he’d spend his time. He would begin his journey in Louisiana before traveling to three other Southern states: Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. As he traveled, he’d embed himself in Southern Black communities by looking for work, forming friendships, and talking to Black residents. Throughout his journey, he’d keep a diary of his experiences and insights.

(Shortform note: Griffin’s approach is an example of investigative journalism. Investigative journalists conduct in-depth research with the goal to expose a problem. To accomplish this, they often embed themselves in a new environment for an extended period. Griffin wasn’t the first to use investigative reporting techniques to expose racism in the South. For instance, in the late 19th century, Black journalist Ida B. Wells investigated the lynchings of Black Southerners. Her reporting raised public awareness about racist lynchings.)

Griffin’s Findings

In Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin discovered on his six-week journey that his hypothesis was true: Black Southerners faced racism in their daily lives. We’ll begin this section by explaining how racism limited Black Southerners’ access to public amenities and how this lack of access shaped their daily lives. Then, we’ll explore white Southerners’ racist treatment of Black Southerners. Finally, we’ll describe Black Southerners’ strategies for navigating everyday racism.

Insight 1: Black Southerners Lacked Access to Public Amenities

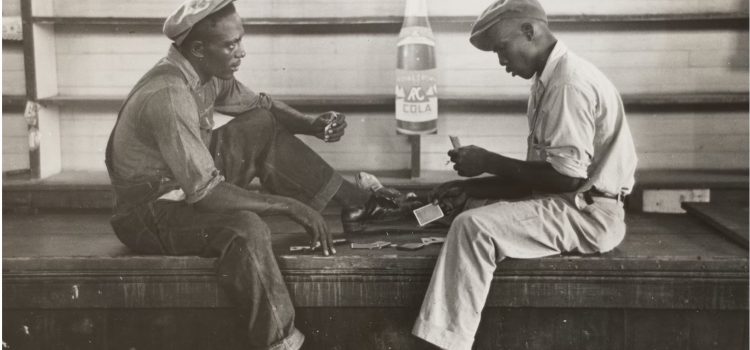

First, Griffin contends that due to racism, Black Southerners lacked access to public amenities such as parks, water fountains, bathrooms, and places to relax. This lack of access made it hard for Black Southerners to meet their basic needs. Griffin was struck by how much daily time he spent searching for Black-friendly bathrooms, resting spots, and places to eat and drink. Let’s explore two reasons behind Black Southerners’ lack of access to such amenities.

Insight 2: Black Southerners Faced White People’s Individual Racism

Second, Griffin reflects that while he was disguised as a Black man, some white people treated him and the Black people around him with kindness and politeness; however, most showed some degree of racism.

Griffin argues that many white Southerners treated him like a stereotype of a Black man, rather than like a human. Let’s examine three of these stereotypes:

- First, white people stereotyped him as hypersexual. For instance, while Griffin was hitchhiking through the Deep South, several of the men who picked him up asked him intrusive questions about his genitalia and sexual history.

- Second, white people stereotyped him as unintelligent. At one point, a white man giving Griffin a ride expressed shock when he realized that Griffin was intelligent.

- Lastly, white people stereotyped him as a criminal. For example, multiple store clerks refused to cash Griffin’s traveler’s checks because they suspected he stole the checks.

Insight 3: Black Southerners Had Strategies for Navigating Racism

Although John Howard Griffin makes it clear in Black Like Me that Black Southerners experienced overwhelming racism in their daily lives, he doesn’t portray them as helpless victims. He claims that Black Southerners developed strategies for surviving everyday racism. Let’s explore three of these strategies.

Protective Compassion: First, Griffin was struck by the immense compassion Black Southerners showed him and each other—compassion that exceeded the typical kindness of strangers. He asserts that they did so to compensate for the harm of racism and to offer protection from racial hatred. For instance, a young Black student walked with Griffin for two miles to show him to the closest theater; a Black man Griffin met on the bus helped him to find a safe ride home and a hotel; and several Black families generously invited Griffin to stay in their homes, despite their poverty.

Exchanging Advice: Second, Griffin claims that while he was disguised as a Black man, he noticed that Black Southerners frequently exchanged advice on safely navigating everyday racism. For example, when Black passengers seated near Griffin on the bus learned that he was from out of town, they shared advice on social norms he must follow to keep safe in this new city.

| Large-Scale Mutual Support Among Black Americans Griffin’s accounts of Black people’s protective compassion and advice-giving focus on individual acts of kindness and support. However, mutual support among Black people goes beyond these one-off instances of individuals helping individuals. There’s a long history of Black mutual aid communities in the US. These Black-led groups provided (and continue to provide) Black communities with resources in times when the government has failed to do so. Here are several examples of Black mutual aid efforts throughout history as well as today: – During the 18th and 19th centuries, several US societies such as the New York African Society for Mutual Relief and the Phoenix Society provided Black community members with everything from health insurance to clothing. – In the 1950s, several Black women in Alabama formed The Club from Nowhere, a mutual aid group that ran bake sales to help fund the Montgomery Bus Boycott. – Starting in the 1960s, The Black Panther Party ran a free breakfast program for Black children. Churches, individuals, and stores donated enough food to feed 20,000 children breakfast every morning before school. – Starting in 2020, many Black people began mutual aid networks to serve communities of color that were hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. Some of these networks take inspiration from the Black Panther Party’s efforts decades ago. These mutual aid efforts illustrate that throughout history, Black people have organized large-scale support networks that enable their survival. |

Striving For Dignity: Finally, Griffin argues that Black Southerners who faced racism still strove for dignity. They engaged in subtle acts of resistance that conveyed their refusal to be degraded.

For example, John Howard Griffin describes a bus ride in Black Like Me where Griffin and several Black passengers noticed that the white bus driver only told white passengers to watch their step as they entered and exited. At one point, a group of white people approached the door to exit, and they were followed by a Black woman. When the bus driver told the group of white people to watch their step, the Black woman politely responded, “Thank you.” This small act of resistance infuriated the white bus driver—and brought the bus’s Black passengers some momentary joy.

(Shortform note: In The Jim Crow Routine, Stephen Berrey argues that while subtle, spontaneous acts of resistance like the one Griffin describes here may seem insignificant compared to major acts (such as revolution), small forms of defiance were still impactful. He explains that such acts had two effects: 1) They gave Black people a sense of control, and 2) they reminded white people that they weren’t superior. These two effects weakened the force of Jim Crow laws, which (as previously noted) were designed to make white people feel superior in interracial spaces. For example, Black Southerners were expected to make room on the sidewalk for white people passing by, but Black residents often refused to do so.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of John Howard Griffin's "Black Like Me" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Black Like Me summary:

- The 1959 story of a white man who spent six weeks living as a Black man

- The brutal racism Black southerners faced in the mid-1900s

- Griffin’s insights about hope for racial progress in the South