This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Cancer Code" by Jason Fung. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is the Atavistic Theory of cancer? How does the Atavistic Theory explain cancer prevalence?

According to the Atavistic Theory, cancer results from the re-emergence of traits from the earliest single-celled organisms, caused by evolutionary pressure from carcinogens. Atavism explains why cancer can be found in nearly every animal species on Earth: It’s because the traits of cancer come from our oldest common ancestors.

Keep reading to learn about the Atavistic Theory of cancer.

Cancer as Atavism

In his book The Cancer Code, Jason Fung presents a newer hypothesis about cancer. This model was not proposed by a biologist, but by physicist Paul Davies, whom the National Cancer Institute reached out to in 2009 in the hope that an outsider’s viewpoint could provide some new insights about cancer. Specifically, Davies proposed that cancer is an atavism: an evolutionary throwback in which ancestral traits re-emerge in modern organisms.

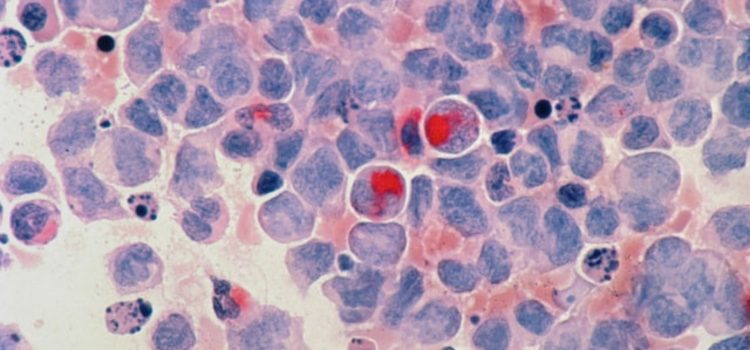

To support this idea of cancer-as-atavism, Fung points out that cancer cells act like simple organisms: They grow, feed, reproduce, and evolve. Therefore, rather than the concept of random mutations causing cells to run wild, this hypothesis says that cancer’s behavior is actually extremely logical and focused on survival; not the survival of the host, but of the cancerous “organism.”

(Shortform note: At the beginning of The Selfish Gene, Dawkins gives a biologist’s answer to the age-old question of why life exists: to survive and reproduce. Model 3 is suggesting that’s exactly what cancerous cells are doing—surviving and reproducing by any means necessary. That’s why Fung says they behave like organisms.)

Furthermore, genetic evidence for this theory in addition to the behavioral evidence—mutations in cancerous cells are most likely to affect those genes that evolved shortly after the first multicellular organisms emerged, effectively reverting them to the genes of single-celled organisms.

(Shortform note: The human genome contains an incredible amount of what, until recently, scientists called “junk DNA”—genetic material that doesn’t seem to serve any purpose. While we’ve recently discovered that some of this DNA does serve a purpose within the body, that “junk” also includes pseudogenes, which scientists believe are essentially evolutionary leftovers. In other words, pseudogenes are broken or suppressed copies of genes that our ancestors carried. Model 3, cancer-as-atavism, could mean that some of those suppressed genes are reactivating.)

In other words, malignant cells didn’t need to evolve cancerous traits from scratch, because the genes for the traits were already in their DNA. The cells just needed to evolve (or devolve) in such a way that those genes reactivated.

Fung says that the model of cancer as an evolving species solves the two major shortcomings of the somatic mutation theory. First, cancer does not spring up at random—the elements of cancer are already present in our DNA, so all the cell needs to become malignant is for those genes to reactivate. This provides a much more satisfactory answer to cancer’s prevalence than random chance could.

Second, the atavistic model reveals that genetically-targeted treatments are mostly ineffective because of cancer’s genetic variation. After turning cancerous, cells continue to divide and mutate extremely quickly, meaning that even cancerous cells within a single patient can have countless different genetic traits. So, while a targeted treatment will kill many of the malignant cells, it’s very likely that some will be resistant to it. Even worse, those surviving cells will continue to reproduce, meaning that cancer can evolve to resist any given treatment.

Therefore, to cure a patient and avoid relapse, doctors must either find and target the root mutation—the original genetic change that all the cancer cells share—or use a battery of different treatments to ensure that every malignant cell is destroyed.

| Counterpoint: The Atavistic Theory of Cancer Isn’t Totally New To pose a partial counterpoint to Fung, doctors have known for decades that not all cancer cells respond to treatment the same way and that multiple treatment methods are much more effective than any single targeted treatment. In The Emperor of All Maladies, Mukherjee describes a number of advancements in treatment that took place in the 1950s and early 1960s. Doctors found that using cocktails of multiple chemotherapy drugs worked significantly better than any single drug and that using radiation therapy in conjunction with chemotherapy further increased the treatment’s effectiveness. They also found that, for a patient to be truly cured without relapsing, every trace of cancer had to be wiped from that patient’s body. So while doctors might not have been thinking of cancer as its own species, they certainly knew that it had genetic variation, as well as the ability to reproduce and adapt, and they treated the disease accordingly. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Jason Fung's "The Cancer Code" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Cancer Code summary:

- A guide on what cancer is and how it works

- A deep dive into the three different models of cancer

- Why there is hope for the future of cancer treatments