This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Behind The Beautiful Forevers" by Katherine Boo. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Is Annawadi from Behind the Beautiful Forevers a real place? What is life like in Annawadi?

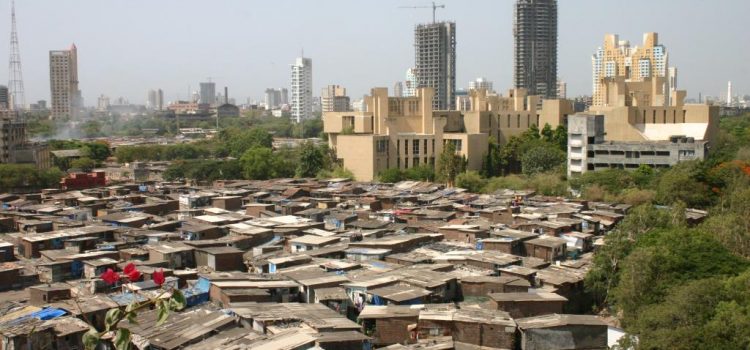

Annawadi is a slum adjacent to the Mumbai International Airport—it was created by the migrant workers that worked there during its construction. Life in the slum is a constant struggle for survival. Residents worked all sorts of odd jobs to make a living.

Read on to learn more about the lives of the residents of Annawadi.

The Residents of Annawadi

Behind the Beautiful Forevers recounts the lives of residents of a slum in Mumbai called Annawadi, which sat adjacent to the Mumbai International Airport..

Katherine Boo, a U.S. journalist married to an Indian, spent four years learning the stories of Annawadi residents through reading public documents, conducting interviews, and observing people’s day-to-day lives. She tells the stories of real people—their names are unchanged—and how a globalized world affected them: Despite India experiencing a new era of wealth, opportunity, and increasing development, many people still struggled to survive day-to-day, even when working harder than ever.

In 1991, India began a period of “economic liberalization,” which led 100 million people out of poverty over time. And yet, Annawadi was founded the same year and persisted. Though governments can create policy to nurture the potential of their people, they sometimes just reinforce corruption instead, and people adapt to the system. The poor tried to exploit one another to get ahead, and police and government officials exploited the poor, leaving the poor with little power and few resources. Nevertheless, many still hoped they could get ahead if they simply worked hard enough.

Part 1 introduces Annawadi, its residents, and their daily struggles.

The Origins of the Slum

Annawadi, a half-acre slum, sprang up in 1991 during repairs to a runway of the Mumbai airport. The workers came from the state of Tamil Nadu and decided to stay in hopes they could get additional construction jobs. “Anna” means “older brother” in Tamil, and Annawadi means “land of the Annas.” The land was swampy, and they worked to pack dry dirt into muddy areas to make it livable. The first huts were made of bamboo poles and empty cement sacks.

By 2008, Annawadi had 3,000 inhabitants. Residents lived in one of three areas:

- An area with small, one-room huts, often with shared walls. It was built near a sewage lagoon fed by public toilets.

- Another area with poorer housing, built by Dalits, members of India’s untouchables caste.

- A road where there was no shelter and the poorest of the poor would sleep atop bags of trash they had picked to keep them from being stolen.

The slum’s sewage lagoon was filled with garbage and pollutants. Airport construction workers also dumped waste there in the middle of the night and one time, something in the lake dyed the bellies of animals that slept near its shores blue. Some people living in the slum made so little money that they had to supplement their diet by catching rats and frogs living near the lagoon, or eating the grass that grew at its edges.

People suffered air-pollution-related ailments, like asthma, as well as tuberculosis and other diseases.

In the Shadow of Wealth

A large concrete wall stood between the slum and main drive to the international terminal of the airport. On the wall, cheerful advertisements hawked luxury items to the “overcity,” or upper classes. One advertised Italian tiles, with the slogan, “Beautiful Forever,” repeated over and over for the length of the wall. Thus, the slum was located “Behind the Beautiful Forevers.”

Despite the slum’s proximity to the airport, only six of Annawadi’s residents held permanent jobs there. One young boy, Rahul, had gotten temp work as a server at one of the hotels next to the airport thanks to his mother Asha’s efforts. As a server in this hotel, he got close to the affluent clientele and their over-the-top parties. He told the other slum dwellers stories of the parties, as well as strict company policies for servers, like not looking directly at the guests. One time, he got into trouble for demonstrating some dance moves at the request of the guests.

Most people did work making cheap goods, like garlands for airport tourists or hanging decorations for people’s car mirrors. Many people no longer felt limited by caste or religious affiliation, and they aspired to better jobs or living situations.

As India modernized and became sensitive to the image presented by the poverty of slums, there was periodically interest in razing Annawadi, but this had yet to come to fruition.

Accidents and Suicides in Annawadi

Annawadi saw a number of deaths and suicides each year. Along Airport Road, it was common for trash pickers to get hit by cars. Passersby from the slum were often too busy with their own affairs to call the authorities for help, or they feared the authorities.

For example, Sunil, a scavenger who had sold trash to Abdul, came across an injured man along the road one day but was too afraid to go to the police for help because he’d heard of Abdul’s torture when he’d been in police custody over Fatima’s burning. The victim passed away later in the day and his body was picked up after someone called the police. There wasn’t any attempt to search for his family, and the morgue pathologist concluded he’d died of tuberculosis even though there was no autopsy. Even the handling of such deaths was driven by money: One of the police officers helping with the case had an arrangement with a local university to provide cadavers to their human anatomy lab, and he was in a hurry to deliver the body.

Additional bodies began showing up along the Airport Road. Most of the dead were from Annawadi. People in Annawadi started to worry that Fatima’s death had left a curse on the slum and wondered anew if the government would go forward with plans to raze it. The local police, for their part, felt increasing pressure from the government to maintain a safe environment around the airport. Officially, only two murders were recorded in the area around the airport, from slums to hotels, over a two-year period. However, deaths were likely undercounted. The deaths of slum residents were largely regarded as a nuisance rather than a problem to fix.

Kalu’s Story

Kalu, one of the young trash pickers Abdul worked with, had come to Annawadi from another slum after his mother’s death. He’d felt like his father and brother didn’t understand him, and he wanted to make a living for himself as a trash picker.

He’d become known for scavenging high-quality recyclables from the airport grounds, but he ran into trouble with the police for doing so—in the eyes of the law, he was trespassing on airport grounds and stealing the goods. The police made a deal with Kalu: He could continue scavenging if he acted as an informant on drug dealers operating around the airport.

Kalu agreed but lived in a constant state of stress. He feared both the police and the powerful drug dealers he ratted on. While hanging out with friends, he liked acting out the plots of movies and kept discussing one about a man who feels so trapped that he drinks liquor to kill himself before being rescued by the film’s heroine.

Because of the stress, Kalu decided to return to his father and brother to try his hand at their line of work—pipe fitting. He’d learned the trade when he was small and knew they were taking on a project that would provide work for him to do. But he didn’t end up staying long. He soon returned to Annawadi in hopes of participating in a festival for his chosen god, Ganpati. Overall, he felt as though he didn’t have a home.

One day, after picking trash and selling it to Abdul, he disappeared and his body was found the next day on the side of Airport Road, like many before him. The police recovered the body and concluded that Kalu had died of tuberculosis, but not before some boys from Annawadi had looked at the body. They could see he’d received severe injuries, and they said he’d been murdered. Moreover, tuberculosis wasn’t something that young, active garbage pickers tended to die of—it caused a slow deterioration before death.

After Kalu’s death, the police rounded up five trash pickers living without shelter in Annawadi, held them, and beat them. To prevent more deaths near the airport, they gave the boys an ultimatum: Either stop picking trash along Airport Road and at the airport or face being charged with murdering Kalu. The police didn’t tell the boys that they had already attributed Kalu’s death to tuberculosis in their official report.

Sanjay’s Story

Sanjay was one of the trash pickers taken into custody by the police after Kalu’s death. He had witnessed a group of people beating Kalu near the section of the airport where he usually picked trash on the night he died. It was possible Kalu had gotten caught by the airport authorities, or that the drug dealers he informed on had caught up with him.

After being beaten by the police and having his livelihood threatened, Sanjay feared the police might torture him again, or Kalu’s murderers would hurt him for having witnessed their crime. He picked one last batch of trash to sell to Abdul so that he could afford to travel to the slum where his mother and sister lived.

He arrived at his family home and spent the evening giving advice to his sister, with whom he was close, before his mother came home from her job in a middle-class home. His sister listened for a while, but then returned to preparing dinner while Sanjay appeared to take a nap.

When his mother arrived home, she talked to Sanjay briefly as he sang one of his favorite sad songs. She went to the bathroom, and when she came out, she and her daughter found Sanjay convulsing on the floor. He had eaten rat poison.

They got him to the hospital—the same one Fatima went to—but he only survived for two hours. The doctors gave his mother prescriptions to fill, but she didn’t have time before he succumbed to the poison. The police wrote in their records that Sanjay was a heroin addict who had committed suicide because he lacked money to buy more of the drug.

Meena’s Story

Manju, Asha’s daughter, had a 15-year-old friend named Meena, who was considered to be the first girl born in Annawadi. They would often visit the public toilet together to commiserate about the pressures and hardship they faced as girls. Meena faced regular beatings from her father and older brother. Despite threats of violence, Meena often voiced her discontent to her family, which then resulted in more beatings.

Meena’s family planned to marry her off to a boy in a rural village. From watching Indian soap operas, Meena could see that there were now opportunities for Indian women to lead more independent lives, but she couldn’t figure out how to build that kind of life for herself. She thought Manju might have more opportunities if she graduated college, but Manju hadn’t graduated yet and Meena didn’t know other women who had. She felt as though she couldn’t decide anything herself and anticipated she’d feel even more restricted in marriage.

One day, Manju found Meena sitting on her front step, which was usually not tolerated by her family. Meena said she had taken rat poison. When Manju tried to ask Meena’s mother for help, her mother thought that Meena was lying about taking the poison so she could avoid being beaten by her brother for the third time that day.

Manju tried to find help for Meena but she needed to be discreet—shouting for help would advertise that Meena had tried to kill herself and might hurt her marriage prospects. Manju got help from some nearby women, who fed Meena salt water to induce vomiting. When that didn’t work, they tried soapy water. Meena vomited and said she felt much better. When her brother arrived home, he heard she had taken rat poison and beat her for it.

A few hours later, Meena was in pain from the poison—the induced vomiting hadn’t cleared it from her body. Her father took her to Cooper Hospital. The police asked Meena if anyone had pressured her into taking poison, but she said it was her own idea. The hospital asked for payment from her family for a special medicine, but it wasn’t sufficient and she died within a few days.

The women who had tried to help Meena recognized that she felt trapped—she was tired of bending to her parents’ will. But Meena’s family saw her friendship with Manju as the cause of her death: Manju had corrupted Meena with her efforts to dress differently and climb the social ladder.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Katherine Boo's "Behind The Beautiful Forevers" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Behind The Beautiful Forevers summary :

- A nonfiction account of the lives of residents of in one Mumbai slum

- How the globalized world affects many people in India

- A story of poverty, exploitation, and the struggle to survive