This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Art of War" by Sun Tzu. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Who was Sun Tzu, and why is he important? What was Sun Tzu’s military philosophy?

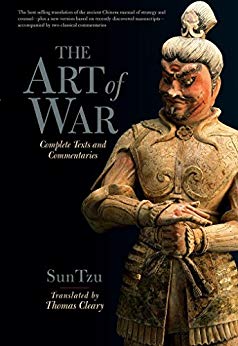

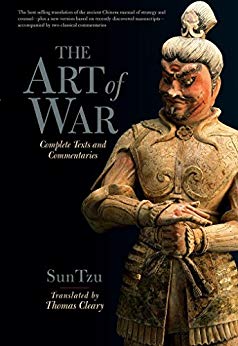

Sun Tzu is an influential figure in ancient Chinese history. Sun Tzu’s book The Art of War, written over two thousand years ago, remains an iconic text on military strategy and conflict resolution. Sun Tzu’s principles guide you through the steps required to become a competent leader and fighter. They also teach you how to determine victory, when to engage in combat, and when to use intelligence and intimidation to dissolve conflict without confrontation.

The following are some historical examples that augment Sun Tzu’s principles of war.

The Art of War

One of the first documents on warfare strategy in history, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War has become a revered military text. Sun Tzu was a Chinese general and a military strategist who lived in the Eastern Zhou period of ancient China. Although his teachings are geared toward actual military conflict, the principles can be useful in all arenas of conflict or competition, even at a personal level.

Historical Example: Reward

General Cao Cao was a well-respected and renowned military leader in Chinese history who avidly abided by Sun Tzu’s Art of War. Toward the end of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. to 220 C.E.), Cao Cao often invaded enemy territories. During these raids, he would acquire a trove of valuable treasures, whether rare objects or gold. Whenever these spoils were retrieved, he would divvy them out to those who showed incredible strength and effort. He was generous with his rewards. Those who did not show exceptional prowess or effort received nothing. In this way, his soldiers were motivated to work hard, and he was able to be successful in most of his battles.

Historical Example: Ending Conflict Before It Begins

During the Spring and Autumn Era (722 to 481 B.C.E.), when the Zhou dynasty was beginning to collapse, the state of Jin wanted to overtake the state of Qi, a much smaller state. The Jin sent an emissary to scope out the Qi. The emissary, feigning drunk aggression, insulted the Qi’s ruler and tried to force the Qi to disregard etiquette. When the Qi did not react to the insult and did not abide the aggressive demand, the emissary returned home and told the Jin leadership that the Qi were alert, cautious, and prepared. Therefore, they should not be attacked at this time. The Qi were able to thwart armed battle through intelligence.

Historical Example: The Consequences of Battle Without Strategy

Toward the end of the sixth century, two empires were in conflict for supremacy: the Zhou and the Qi. The Zhou ruler wanted to attack a valuable Qi territory, but one of his advisors cautioned against it. The advisor expressed concern over the large and highly trained Qi forces tasked with defending the territory, stating that even if they attacked with their full strength, they would not be able to take the territory easily, if at all. He suggested attacking a smaller, less valuable territory, where victory was more assured. The Zhou ruler ignored this warning and went ahead with the attack, losing the battle and many men and resources along the way.

Historical Example: Exploiting Momentum

In 265 C.E., the martial emperor of Jin defeated Cao Cao’s forces in the north and wanted to overthrow another kingdom, the Wu, to gain supremacy in the south. One of Jin’s generals won a small battle against a faction of the Wu’s military. The general then asked for permission to carry out a full assault on the Wu. Knowing the large amount of strength, supplies, and men it would take to overthrow the Wu, the emperor denied the request, suggesting they wait a year to prepare.

The general, in response, cautioned that their plans against the Wu are now apparent. The Wu could begin preparations during the year in anticipation of an assault. The general stated that the momentum was on their side currently, and the likelihood of victory at that moment was large compared to their chances in the future. The emperor agreed, and the general was successful in taking over Wu territory easily.

Historical Example: Using Distance as an Advantage

After the fall of the Han dynasty, three kingdoms—the Wu, Shu, and Wei—battled during what was known as the Era of the Three Kingdoms (190 to 265 C.E.). The general of Shu joined forces with the Wei, becoming a military governor of what was called “New City.” However, soon after, he defected to the Wu, again switching his allegiance.

The Wei general was advised by his commanders to send scouts to observe the actions of the Shu and Wu before reacting. But the Wei general wanted to take advantage of the uncertainty of loyalty that would necessarily follow such a flip-flopping of allegiance. The Wei general sent a force to New City, traveling day and night. Meanwhile, the defector assured his commanders that the Wei was too far away. He said his troops would be fortified and ready by the time the Wei learned of his actions and mobilized.

When the Wei arrived eight days later, surprising everyone with their swiftness, they easily pushed through the defector’s ill-prepared army and forced a surrender.

Historical Example: Suspicious Surrender

When one of Cao Cao’s rivals surrendered to him, Cao Cao allowed the rival to return home. Shortly after, the rival returned to attack Cao Cao and killed Cao Cao’s son and nephew. Cao Cao also suffered an arrow injury.

The rival returned again with an armed force, but Cao Cao was successful in defending against them. On reflection, Cao Cao blamed his benevolence and negligence in letting the rival go for the fate of his family and army, advising his commanders to never make such an egregious error.

Historical Example: Forming Alliances

During the Three Kingdoms Era, the Shu army surrounded a faction of the Wei military. Cao Cao, a Wei general, wanted to relocate the rest of the Wei’s capital away from enemy lines for safety. But a minister of Wei advised against such an action, stating that it exuded weakness. Instead, he said they should form an alliance with the state of Wu. The Shu and Wu were considered to be allies, but the minister knew this was only a surface appearance. He assumed the Wu leadership would begrudge the Shu gains.

Cao Cao agreed and sent an emissary to create an alliance with Wu, who was tasked with attacking the Shu from the back. The Wu were successful, and the Shu retreated from its position surrounding the Wei army.

Historical Example: The Benefit of Reverse Spies

During the sixth century, there was a general of the court of Zhou who was well-liked, charismatic, and good at his job. He employed many spies within the court of Qi and the Qi community, and his generosity and benevolence made them loyal. Therefore, Zhou knew everything that was happening in Qi.

The Zhou general devised a plan to plant a song within the Qi kingdom that suggested the prime minister of Qi was planning a coup against his military. A Qi spy helped spread the song, and a rift grew between the prime minister and a Qi general, leading to the former’s execution. Once the Zhou general learned of the execution, he launched an attack against the Qi kingdom and destroyed it.

Historical Example: A Properly Trained Force

Confucius stated that allowing forces not properly trained to enter battle is the same as abandoning your forces in enemy territory.

Another leader, Wu Qi, a general for the Wei state, advised that the first task of any military action is to properly train the forces. Teach a few to fight, and they will expand and teach others to fight, and so on until a large fighting force is amassed.

Soldiers must be trained in all the tactics and strategies possible within a conflict, such as when to strike and when to retreat, when to fortify and when to divide, and when to use resources and when to feed off the enemy. Only after they have learned and mastered these skills and considerations should they be given weapons. Creating experts in battle before providing the tools of battle is the foundation of a good leader.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Art of War" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Art of War summary :

- How to mislead your enemies to win the war

- Classic examples from Chinese history to illustrate Sun Tzu's strategies

- How to use spies to gather information and defeat your opponents