This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" by Malcolm X and Alex Haley. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Why was Malcolm X in prison? How did his life change dramatically when he was incarcerated?

Malcolm X’s childhood was steeped in adversity, and it didn’t take long for him to turn to crime. When he was just 20 years old, he was sent to prison after being convicted on burglary charges in Boston. Six years later, he emerged a different man than he was when he went in.

Keep reading to learn about Malcolm X in prison, as presented in his autobiography.

Malcolm X in Prison

For a young Malcolm X, prison might have seemed like an inevitability considering the path he was headed down. He started by stealing food to eat. As a teenager, he got drawn into the ghettos of Boston and New York City where drugs and hustling were the order of the day.

After living in Harlem for about two years, Malcolm X returned to Boston in 1945. There, he decided to start a burglary ring involving his friend Shorty, their friend Rudy, Malcolm X’s girlfriend Sophia, and her sister. Since the women were white, they could get into houses by pretending to have legitimate business there (like selling encyclopedias, for example), which Black men couldn’t do without arousing suspicion. When they left, they could tell the men how the house was set up and where there were any items worth stealing. Their burglary scheme was successful, but Malcolm X explains that he continued doing a lot of drugs to help him deal with his anxiety about being caught.

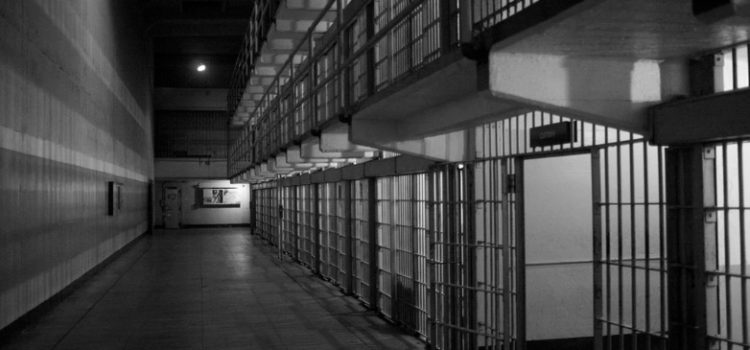

Eventually, they were caught—and, in 1946, Malcolm X was sentenced to eight to 10 years in prison at the age of 20, despite the average sentence for first-time burglary convictions being only two years. He explains that he believes part of the reason the penalty was so harsh was because he had gotten two white women (who were sentenced to only one to five years in prison) into trouble as well. The prison was dirty with no running water, he felt trapped like an animal, and he was often put in solitary confinement.

(Shortform note: Some historians argue that the American criminal justice system has always disproportionately incarcerated Black men—a trend that persists to this day. In fact, some experts say that racial disparities in the criminal justice system have gotten worse over time. For example, Black men today are likely to receive significantly longer prison sentences than their white counterparts. Historians partially attribute these trends to the “brute caricature” that is often applied to Black men—a stereotype that depicts them as innately dangerous, inhuman, and felonious, especially toward white women. This stereotype may account for Malcolm X’s experience of being judged harshly for being involved in criminal exploits alongside two white women.)

Upon reflection in later life, Malcolm X explains his belief that his imprisonment was inevitable—and that it was also inevitable for countless other Black youths. Since they were largely confined to overpoliced ghettos where crime was rampant, denied the opportunity to receive a good education or get good jobs, and able to get their hands on drugs that would numb the pain of their existence easily, Black people were more likely to engage in crime and get caught for it.

(Shortform note: In The New Jim Crow, legal scholar Michelle Alexander explains that incarceration continues to seem like an inevitability for an increasing proportion of Black men in the United States. She argues that presently, the War on Drugs—an intense crackdown on the possession, use, and sale of drugs that began in the 1970s—is the main mechanism leading to the mass incarceration of Black men. But she notes that this is just a new method to accomplish an old goal: the continued subordination of Black people. Previously—that is, during Malcolm X’s lifetime—Black people were criminalized by unfair laws and applications of justice because their newfound freedom after slavery threatened white supremacy.)

The Nation of Islam Gave Malcolm X a Second Chance

While he was in prison, some of Malcolm X’s family converted to Islam—and they promised that they could help him get out of prison if he, too, joined. The type of Islam Malcolm X’s family tried to convert him to was known as the Nation of Islam—a collection of teachings promoted by Elijah Muhammad (the Nation of Islam’s leader, who succeeded founder W. D. Fard), which posited that white people are the devil and that they’ve perpetrated evil against Black men by cutting them off from their ancestral cultures and convincing them of white superiority.

Malcolm X explains that he was prepared to accept these teachings as the truth because he knew that the way he had been living was wrong—this seemed a viable alternative. To convert, he first stopped smoking cigarettes and eating pork. He then wrote to Elijah Muhammad, who welcomed him to the religion and told him that he was living proof of white men’s devilish nature—since they deprive Black men like him of opportunities and force them to become criminals to survive.

(Shortform note: According to scholars of the Nation of Islam, the organization specifically recruited prisoners after Muhammad was incarcerated for sedition and draft evasion. He believed that prison was a form of oppression, that Black people become criminals because they don’t know they belong to a superior race, and that he could help them realize their true potential and leave crime to the naturally inferior—white people. Prisoners were drawn to the Nation of Islam because it promised a chance at absolution—and provided housing and a job upon release for those who converted.)

Invigorated by his new beliefs, Malcolm X started participating in the prison debate club, arguing in favor of Black superiority and proselytizing to receptive Black inmates. For the last year of his sentence, he was transferred back to the first prison he was incarcerated at—he explains that this was because the authorities deemed his outspokenness about his newfound pro-Black beliefs dangerous. However, he continued debating—and with time, his self-confidence grew.

Malcolm X notes that he was paroled in 1952, having served six years of his sentence, and began living with his family in Detroit.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Malcolm X and Alex Haley's "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Autobiography of Malcolm X summary:

- Malcolm X explains why he believed what he believed

- The historical and sociological context surrounding Malcolm X’s life

- Why Malcolm X was such a controversial figure