This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Deficit Myth" by Stephanie Kelton. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

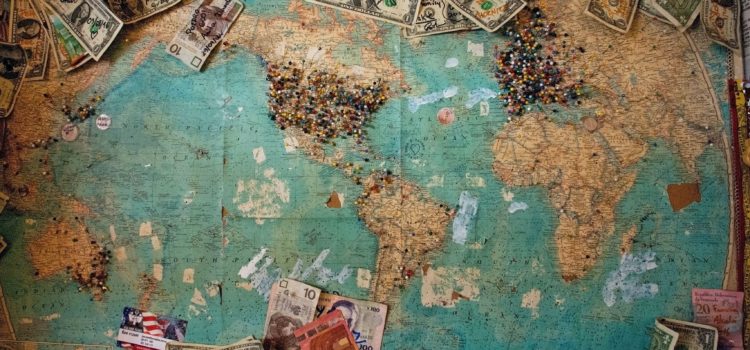

Is a trade deficit a good or bad thing? Could there possibly be benefits to having a trade deficit?

According to Stephanie Kelton, an economist and believer in modern monetary theory, the United States trade deficit is actually a strength rather than a weakness. She believes that the trade deficit puts the United States in a position of power because other countries rely on its currency.

Here’s a more in-depth look at the U.S. trade deficit from The Deficit Myth.

What Is a Trade Deficit?

Trade deficits occur when a country buys more in goods and services from one country than it sells to that same country. If the U.S. buys $500 billion from Japan and sells $250 billion in turn, the U.S. would run a $250 billion dollar trade deficit with Japan ($250 billion – $500 billion = -$250 billion). In that same scenario, Japan would be running a $250 billion surplus with the United States.

Indeed, every trade deficit run by one country must be matched by a corresponding trade surplus run by another country as a simple matter of logic and accounting. By that same logic, it’s impossible for every country to run a trade surplus (or deficit for that matter).

Kelton notes that politicians on both sides of the aisle—in recent years Donald Trump most notably—have promoted the idea that trade deficits represent some kind of “loss” or fleecing of the U.S. at the hands of foreigners. But she notes that this idea betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of macroeconomics.

(Shortform note: Although Trump emphasized economic nationalist themes during his 2016 candidacy and his presidency (including the imposition of tariffs on China), his administration made little headway in the reduction of the U.S. trade deficit. As he was set to leave the White House in 2020, the trade deficit stood at $600 billion, its highest figure since 2008. Experts note that the large fiscal stimulus measures his administration implemented in response to the Covid-19 pandemic played a role, by enabling imports to recover more quickly than exports. They also noted that attempts to adjust trade deficits through one-off policy measures are generally exercises in futility—because trade deficits mostly result from larger structural macroeconomic factors, such as the fact that Americans tend to spend more than they save, which means that they must borrow from abroad in order to make up the difference.)

The Costs of Globalization

Kelton argues that globalization—the freer flow of goods, services, and capital across national borders—has contributed to trade deficits in the U.S. and in other advanced economies because globalization makes it easier for companies and individuals to purchase cheap labor, finished goods, and production inputs from the global market.

She also notes that globalization has undoubtedly inflicted pain on millions of Americans since the 1990s, when the U.S. signed high-profile free-trade agreements like the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Because of free trade, low-skill manufacturing jobs have undergone a major decline in the United States. On net, 2.7 million American jobs have been lost due to outsourcing and offshoring.

(Shortform note: The loss of jobs due to trade imbalances has effects that go far beyond what the raw economics statistics will tell you. According to the National Institutes of Health, opioid-related deaths began their sharp increase in the U.S. in 1999, precisely when the country began experiencing significant job losses due to globalization. The NIH further found that the opioid-related deaths were most heavily concentrated in those former manufacturing communities that had been most heavily affected by losses from international trade. In a 2019 paper, they found that every 1,000 trade-related job losses was associated with a 2.7% increase in opiate deaths.)

Don’t Blame the Trade Deficit

Kelton concedes that this economic pain is real and does indeed merit a federal response. But she argues that doing this does not require eliminating the trade deficit—and that doing so may cause even more economic pain.

The trade deficit does not inherently mean that the U.S. must lose jobs and investment. All it means is that some of the money being transferred from the public sector to the private domestic sector is “leaking out” into the foreign private sector.

In other words, it’s just a deficit. And, as we’ve seen, the federal government has near-unlimited fiscal power to turn those private deficits into private surpluses by running deficits of its own. The government must simply run fiscal deficits in excess of the trade deficit, in order to keep the domestic private sector out of debt—remember, the private sector can’t sustain persistent deficits because private firms and households can’t issue their own currency.

Thus, according to MMT, the U.S. government can make the choice to commit to full employment through fiscal policy—regardless of the state of the trade deficit.

(Shortform note: The U.S. government does currently offer assistance to workers who have experienced job loss due to trade policies. The Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program has been in effect since the early 1980s, and it provides affected workers with a range of benefits and services, including job retraining, income supports (called Trade Readjustment Allowances), support for relocation to another part of the country, wage supplements for workers over the age of 50, and a health insurance tax credit.)

How the Trade Deficit Benefits the U.S.

Is a trade deficit good or bad? Stephanie Kelton argues that the U.S. trade deficit is a source of great national strength—not weakness. In fact, the U.S. has even greater monetary sovereignty than other countries that control their own currencies.

This is because the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency. A full 90% of foreign exchange transactions involve dollars, and international business contracts are still largely denominated in dollars. This means that there is a great demand for dollars—countries need dollars to do business and purchase high value-added U.S. products and services.

Thus, U.S. trade deficits underpin the global trading system by supplying the world with the dollars it needs. This puts the U.S. in a position of strength because it is the sole supplier of a commodity that the world desperately needs. Kelton argues that the U.S. can and should use this leverage to create international trade deals that force trading partners to take action on worker protections, green energy, poverty reduction, and global health.

(Shortform note: Some economists argue that trade deficits can harm countries because they are often the result of large capital inflows from other countries. While foreign direct investment (FDI) can lead to job creation and new economic opportunities, excessive foreign ownership of assets can put a domestic economy at the mercy of foreign investors if they suddenly decide to disinvest and leave the country. Moreover, large foreign firms may displace smaller domestic businesses and end up delivering little in the way of benefits to domestic workers and governments, since many of the profits are ultimately repatriated.)

| Does U.S. Political Dysfunction Threaten the Dollar’s Reserve Status? Although the U.S. dollar is currently the world’s reserve currency, the nation’s political dysfunction could jeopardize that status. The U.S. federal government has a statutory limit on how much it is allowed to borrow in order to meet existing financial obligations. When the Treasury Department informs the president that the government is approaching this limit, Congress is supposed to pass new legislation that raises this figure and allows the government to pay its creditors. To not raise the debt ceiling, therefore, is to force the United States to default on its debt, even though, as Kelton argues, the U.S. has unlimited power to create the dollars it needs to meet its debt obligations. Unfortunately, the debt ceiling has become a political football in recent years, with Congressional Republicans threatening to withhold the votes to raise the debt ceiling to force spending cuts and other policy concessions from Democratic presidents—as happened in 2011 under Barack Obama and may happen again in 2021 under President Joe Biden. Analysts warn that these brinksmanship exercises hurt confidence in the U.S. dollar and U.S. Treasury debt as safe assets—and could cause them to cede some reserve status to other currencies like the euro. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Stephanie Kelton's "The Deficit Myth" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Deficit Myth summary :

- A look at national debt through the lens of Modern Monetary Theory

- How public discourse about national debts and deficits gets the facts wrong

- Why MMT says the U.S. government could finance any program it wishes to create